Comics /

Cult Favorite

Euro Comics

By

Philip Schweier

November 25, 2003 - 08:37

Euro-Comics

Euro-Comics

This week, we get two great articles on Euro comics. The first is by European comic book expert, Marc Jetté. The second article is by Philip Schweier. It provides a solid historical recap for those of you who want to get their feet wet in European comics. Those more interested in the contemporary comics coming from Europe, will find Marc Jetté's article very helpful. As for the column, we planned several other features. If there's anything of interest that you would like us to cover, or if you want to drop us a line, email me.

Hervé

Comics are often regarded as a uniquely American art form, much like jazz. But according to former Marvel editor-in-chief Roy Thomas, it aint necessarily so.

Comics are often regarded as a uniquely American art form, much like jazz. But according to former Marvel editor-in-chief Roy Thomas, it aint necessarily so.

Before a packed room at The University of South Carolina’s Thomas Cooper Library, Thomas explained that the very first comic book published in America was in 1842. “The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck” was in actuality a 40-page reprint of a Swiss comic.

Accompanied by French comic author Jean-Marc Lofficier, Thomas presented a two-day comics symposium at USC-Columbia. Dr. Freeman Henry, a professor of French literature, organized the event as an extension of his curriculum. While the course uses more traditional material, a French comic book entitled Lt. Blueberry, created by Jean-Michel Charlier and Jean "Moebius" Giraud, is also assigned reading. Students are often impressed with the level of sophistication of French comics, as well as their readership.

Comic strips began in the late 1890s, with features such as The Yellow Kid. By 1917 the term “comic book” existed, but these were just reprints of comic strips. "There were comic books then, but they were collected in hardcovers, like Barney Google and his faithful nag, Sparkplug,” Thomas explained.

The birth of adventure-based comics in the United States would not take place until 1929, with the simultaneous debut of Buck Rogers and Tarzan.

Meanwhile, across the pond in Belgium, Georges Rémi, under the nom de plum Hergé, had created Tintin for the Catholic newspaper Le XXe Siècle. The travels of a young reporter and his faithful dog in the Soviet Union were published as a weekly supplement, and were an instant hit. Because the publishing firm’s primary goal was to propagandize rather than make money, the story had fulfilled its initial purpose, and Hergé was able to retain ownership of the property and collect royalties.

Meanwhile, across the pond in Belgium, Georges Rémi, under the nom de plum Hergé, had created Tintin for the Catholic newspaper Le XXe Siècle. The travels of a young reporter and his faithful dog in the Soviet Union were published as a weekly supplement, and were an instant hit. Because the publishing firm’s primary goal was to propagandize rather than make money, the story had fulfilled its initial purpose, and Hergé was able to retain ownership of the property and collect royalties.

By 1948, Tintin’s popularity was undeniable, with over 4 million copies sold as further adventures were translated into over 50 languages.

Part of the success was due to Hergé’s dedication to research, using thousands of photo references, which were broken down into the simplest of lines. Inspired by the artwork of the American strip Bringing Up Father by George McManus, there was an economy to the drawings themselves. The illustrations conveyed all the mystery and intrigue the stories demanded. Today, this style is known as “ligne claire" (clear line), and has been adopted by many European illustrators such as Joost Swarte.

In 1938, Spirou was published by a rival publisher. It told the tale of a young bellhop and his adventures in and around the hotel in which he worked. Spirou would go on to publish French translations of American strips such as Prince Valiant.

In 1938, Spirou was published by a rival publisher. It told the tale of a young bellhop and his adventures in and around the hotel in which he worked. Spirou would go on to publish French translations of American strips such as Prince Valiant.

“In 1942, when the Germans took over Belgium, one of the first things they did was order the discontinuation of the importing of American comics,” said Lofficier. As a result, publishers were forced to wrap up the storylines in very few pages. Belgian artist Edgar P. Jacobs hastily tied up Flash Gordon’s ongoing storyline. Immediately, French publishers began printing knock-offs of characters such as Flash Gordon or Tarzan. “The next week the Nazis went back and said ‘You’re not clear on the concept. We not only don’t want American strips, we don’t want strips that look like American strips.’ ” With American-STYLE comics verboten, this opened up pages in French and Belgian publications for more original material.

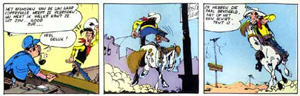

Following the end of the war, many artists immigrated to the United States in search of jobs with Walt Disney. Most were unsuccessful in this endeavor and returned to Belgium and France where they created original characters for children’s magazines. Lucky Luke, a cowboy comedy which pitted a hapless hero against the Dalton Brothers debuted in Spirou. The series was very successful, and spawned a film version in 1991 starring Terence Hill.

Following the end of the war, many artists immigrated to the United States in search of jobs with Walt Disney. Most were unsuccessful in this endeavor and returned to Belgium and France where they created original characters for children’s magazines. Lucky Luke, a cowboy comedy which pitted a hapless hero against the Dalton Brothers debuted in Spirou. The series was very successful, and spawned a film version in 1991 starring Terence Hill.

To compete with Spirou, Tintin magazine, was launched in 1948 and supplemented its content with other original concepts. Among these was Edgar P. Jacobs’ Blake & Mortimer, the adventures of an MI-5 agent and his scientist partner.

The comics market also expanded in other countries. In Italy, comics are known as “fumetti” – literally “little smoke – referring to the speech balloons. Like the American strips before, France imported many of these for publication, proving to be edgier and more adult-oriented compared to what was being published in France at the time.

Many parents disapproved, especially as the more mature titles were often displayed in and around the more juvenile fare. Foreshadowing the establishment of the comics code authority in the United States, France created a censorship committee which hounded many publishers into bankruptcy, both creatively and financially.

As artists became more and more disgruntled, many eventually formed Pilote in 1959. The magazine was an initiative of comics writers René Goscinny and Jean-Michel Charlier, artist Albert Uderzo and Jean Hébrard. Since Charlier and Goscinny were founding fathers of the magazine, they took on most of the initial writing. Goscinny, a close friend and collaborator of Mad magazine’s Harvey Kurtzman, took on 'Le Petit Nicolas' with Jean-Jacques Sempé and his biggest hit ever: 'Astérix' with Uderzo.

“The two things that make this important is,” says Lofficier, “1) the humor of the series was also meant to reach an adult audience, in the sense that it contain the same kind of political satire you might find in Doonsbury, which is unusual because at the time comics were written for an audience of 8-12 years old.

“The second thing is a result of the previous thing, in that suddenly instead of selling 20-25,000 copies – which is sort of the norm for a successful children’s book – the comic sold half a million to a million and a half copies,” Lofficier continues. “Suddenly the world takes notice and you get the cover of Time magazine.”

In 1962, the publisher of Vie magazine, which was similar to the New Yorker in content, requested author Jean-Claude Forest to develop a new science fiction series for the magazine. The result was sexually charged Barbarella, which reflected the counter culture movement that was beginning to sweep England and France.

By 1964, comics in Belgium were recognized as legitimate literature. Other notable appearances in Pilote are the western 'Lt. Blueberry', conceived by Charlier and Giraud in 1963, and the transfer of Morris's 'Lucky Luke' from Spirou to Pilote in 1968.

As the 1960s progressed, comics companies such as Editions Lug began publishing translations of Marvel Comics, which had exploded onto the American scene a few years before. They were as popular overseas as they were in the States, so it was only a matter of time before French publishers began imitating Marvel in creating new, engaging heroes.

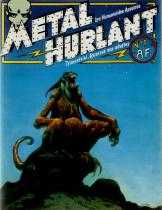

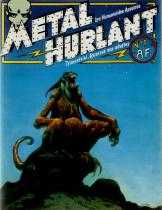

Into the arena in 1973 stepped Metal Hurlant, founded by Jean-Pierre Doinnet, Philippe Druillet, Bernard Farkas and Jean Giraud, also known as Moebius. It was very cutting edge, and was the direct inspiration for its American cousin, Heavy Metal. Four years later, Leonard Mogel, publisher of National Lampoon, was in Paris at the time and enjoyed the magazine so much, he developed an American version. Heavy Metal began by reprinting translated versions of stories from Métal Hurlant, but gradually moved into publishing it's own original material.

Into the arena in 1973 stepped Metal Hurlant, founded by Jean-Pierre Doinnet, Philippe Druillet, Bernard Farkas and Jean Giraud, also known as Moebius. It was very cutting edge, and was the direct inspiration for its American cousin, Heavy Metal. Four years later, Leonard Mogel, publisher of National Lampoon, was in Paris at the time and enjoyed the magazine so much, he developed an American version. Heavy Metal began by reprinting translated versions of stories from Métal Hurlant, but gradually moved into publishing it's own original material.

This also led to the creation in 1980 of a similar magazine from Marvel entitled Epic. This provided a forum for many fully painted comics in the tradition of European comics. Among these was Jon J. Muth’s Moonshadow.

Spain lagged behind due to the state censorship imposed by Generalissimo Francisco Franco. But following his death in 1975, a wealth of new magazines sprang up, most notably El Vibora (The Viper), by Javier Mariscal. His main characters were Fermin and Piker – Los Garriris, distant cousins to Krazy Kat. The strip harkens back to the innocence and enthusiasm of the 1950s.

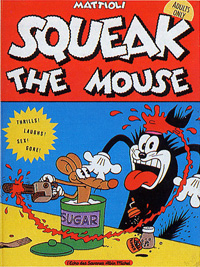

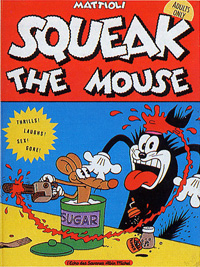

Meanwhile, Italian Massimo Mattioli created Squeak the Mouse, which could arguably inspire the likes of The Simpsons’ Itchy & Scratchy cartoons.

Meanwhile, Italian Massimo Mattioli created Squeak the Mouse, which could arguably inspire the likes of The Simpsons’ Itchy & Scratchy cartoons.

In 1977, Star Wars burst onto movie screens all over the world, leading to a renewed demand for mature, intelligent science fiction for adults. Among the products were L’Incal by Alexandro Jodorowski, a Chilean filmmaker, & Moebius in 1980.

While European influences were being felt in America , super-hero titles were still going strong, and they in turn influenced French comics. Lug, a company originally established in 1950, had published translated version of some of Marvel’s most popular characters. Throughout the 1970s and ‘80s, Lug created a universe of characters which were published well into the 1990s. Lug was absorbed by the publisher Semic S.A. in 1994, who revived and/or revamped many of the characters, as well as adding new ones. They are currently reprinting many of their comics in a trade paperback format. These publications are appealing to older audiences for their nostalgia, while winning over new readers in their teens. “Strangers,” a group of French super-heroes, has recently been licensed for publication in the United States from Image Comics.

Praise and adulation? Scorn and ridicule? Email me at philip@comicbookbin.com.

PAST COLUMNS

Will Lightning Strike Twice?

Euro Comics

State of the Market

This is your captain?

The Incredible Hulk DVD Collection

DC vs. Marvel

Death, Take a Holiday!

Looking In on The Outsiders

News Bytes From The DC Universe

A Whole lot of Chaykin Goin' On

Superman/Thundercats (no, I'm not kidding)

Rucka Retires...

Why Jim Steranko Deserves all the Awards he Can Get

Are Trade Paperbacks the Future of Comics?

Crisis in the Infinite Continuity

How old is Batman?

Humour in Comics

Why Kids Don't Read Comics?

Superman Who?

Last Updated: November 29, 2025 - 16:51

Euro-Comics

Euro-Comics

Comics are often regarded as a uniquely American art form, much like jazz. But according to former Marvel editor-in-chief Roy Thomas, it aint necessarily so.

Comics are often regarded as a uniquely American art form, much like jazz. But according to former Marvel editor-in-chief Roy Thomas, it aint necessarily so.

Meanwhile, across the pond in Belgium, Georges Rémi, under the nom de plum Hergé, had created Tintin for the Catholic newspaper Le XXe Siècle. The travels of a young reporter and his faithful dog in the Soviet Union were published as a weekly supplement, and were an instant hit. Because the publishing firm’s primary goal was to propagandize rather than make money, the story had fulfilled its initial purpose, and Hergé was able to retain ownership of the property and collect royalties.

Meanwhile, across the pond in Belgium, Georges Rémi, under the nom de plum Hergé, had created Tintin for the Catholic newspaper Le XXe Siècle. The travels of a young reporter and his faithful dog in the Soviet Union were published as a weekly supplement, and were an instant hit. Because the publishing firm’s primary goal was to propagandize rather than make money, the story had fulfilled its initial purpose, and Hergé was able to retain ownership of the property and collect royalties.

In 1938, Spirou was published by a rival publisher. It told the tale of a young bellhop and his adventures in and around the hotel in which he worked. Spirou would go on to publish French translations of American strips such as Prince Valiant.

In 1938, Spirou was published by a rival publisher. It told the tale of a young bellhop and his adventures in and around the hotel in which he worked. Spirou would go on to publish French translations of American strips such as Prince Valiant.

Following the end of the war, many artists immigrated to the United States in search of jobs with Walt Disney. Most were unsuccessful in this endeavor and returned to Belgium and France where they created original characters for children’s magazines. Lucky Luke, a cowboy comedy which pitted a hapless hero against the Dalton Brothers debuted in Spirou. The series was very successful, and spawned a film version in 1991 starring Terence Hill.

Following the end of the war, many artists immigrated to the United States in search of jobs with Walt Disney. Most were unsuccessful in this endeavor and returned to Belgium and France where they created original characters for children’s magazines. Lucky Luke, a cowboy comedy which pitted a hapless hero against the Dalton Brothers debuted in Spirou. The series was very successful, and spawned a film version in 1991 starring Terence Hill.

Into the arena in 1973 stepped Metal Hurlant, founded by Jean-Pierre Doinnet, Philippe Druillet, Bernard Farkas and Jean Giraud, also known as Moebius. It was very cutting edge, and was the direct inspiration for its American cousin, Heavy Metal. Four years later, Leonard Mogel, publisher of National Lampoon, was in Paris at the time and enjoyed the magazine so much, he developed an American version. Heavy Metal began by reprinting translated versions of stories from Métal Hurlant, but gradually moved into publishing it's own original material.

Into the arena in 1973 stepped Metal Hurlant, founded by Jean-Pierre Doinnet, Philippe Druillet, Bernard Farkas and Jean Giraud, also known as Moebius. It was very cutting edge, and was the direct inspiration for its American cousin, Heavy Metal. Four years later, Leonard Mogel, publisher of National Lampoon, was in Paris at the time and enjoyed the magazine so much, he developed an American version. Heavy Metal began by reprinting translated versions of stories from Métal Hurlant, but gradually moved into publishing it's own original material.

Meanwhile, Italian Massimo Mattioli created Squeak the Mouse, which could arguably inspire the likes of The Simpsons’ Itchy & Scratchy cartoons.

Meanwhile, Italian Massimo Mattioli created Squeak the Mouse, which could arguably inspire the likes of The Simpsons’ Itchy & Scratchy cartoons.