- Comics

- Comics Reviews

- Manga

- Comics Reviews

- European Comics

- News

- Comics News

- Press Releases

- Columns

- Spotlight

- Digital Comics

- Webcomics

- Cult Favorite

- Back Issues

- Webcomics

- Movies

- Toys

- Store

- More

- About

By Leroy S. Douresseaux

October 28, 2007 - 13:42

|

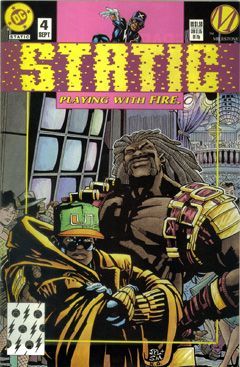

| Static and Holocaust strike a pose. |

STATIC #4

Debuting in Spring 1993, Static was one of the early comic book series created by Milestone Media, and like all Milestone titles, published by DC Comics. Milestone Media was a comic book imprint and media company established with the intention presenting more minority characters in American comic books. While many fans insisted on seeing Milestone solely as a “black comics,” publishing line, the company’s titles had the most diverse cast ever presented in American superhero comics. Although Milestone Media stopped producing comics in 1997, Static became the WB animated series, “Static Shock.”

Static #4 (with a cover date of September 1993) is entitled “Playing with Fire,” and it picks up right where Static #3 left off. It seems that Tarmack, the villain Static/Virgil Ovid Hawkins battled in issue three, was merely a pawn in a plan by former Blood Syndicate member, Holocaust, to test Static’s game. After a momentary standoff, Static agrees to hear what Holocaust has to say.

Holocaust is all about himself – getting “his” before someone else gets it. Static listens attentively, understanding what Holocaust has to say even if he isn’t exactly sympathetic. Holocaust is apparently in an ongoing feud with crime boss Giacomo Cornelius, whom Holocaust accuses of being a parasite on the black community because he sells heroin, prostitutes, and gambling to black people. Static, somewhat reluctantly, joins Holocaust to raise a little havoc in front of Giacomo’s palatial estate – mostly blasting security men and guard dogs.

After those festivities, Static thinks the he needs to talk to someone about what Holocaust is offering – a partnership that would see the two shaking down rich criminals for money. The only person with whom Virgil can share this is his friend Frieda Goren, because she knows that he is Static. Later that night, Virgil waits for Frieda at her house only to discover Frieda and Larry, Virgil’s thuggish homeboy, locked in a passionate embrace. Virgil is embittered because he feels that Frieda and/or Larry should have told him about their relationship, since both knew how Virgil feels about Frieda, so he storms off. This incident convinces Virgil that Holocaust is right: look out for number one!

But before he returns to Holocaust, Virgil spends the next morning in the middle of some domestic drama with his mother and sister who are two sistas with too, too much attitude. Later, hanging out at the comic book shop with some more friends, Virgil learns that they also knew about the Larry/Frieda team up, and that becomes one more embarrassment that stiffens Virgil’s resolve to join Holocaust in what basically amounts to armed extortion.

This time when Holocaust and Static assault Giacomo’s estate, they actually break into the main house. To make sure that Giacomo Cornelius takes him seriously and respects him, Holocaust decides to rough up Giacomo’s young son. Static decides that Holocaust is going too far, and he protects the boy, which severs the tenuous Static/Holocaust union. Strangely, Holocaust doesn’t appear too angry, as he believes Static will be back. Static’s change of heart also extends to Larry and Frieda, and all ends well for the time being.

The story goes: if Steve Ditko had remained on The Amazing Spider-Man as long as he originally intended (issue #38 was his last), he would have taken Peter Parker/Spider-Man into adulthood and maturity so that Parker would be able to discern good and evil objectively with no gray area between the two. Writers Robert L. Washington and Dwayne McDuffie take Virgil/Static to a similar place. Holocaust appeals to the angry young man in Static. Virgil is unsatisfied with his domestic life. His mother and older sister are at times little more than harpies, and Virgil also feels the sting of both institutionalized bigotry and overt racism (which the writers handle is so subtle a fashion).

What Washington and McDuffie present is an opportunity for their young hero to judge right and wrong and use his powers accordingly. In the end, the direction which he takes as a superhero is not based on his personal misfortunes, but in his personal belief in doing what is right.