- Comics

- Comics Reviews

- Manga

- Comics Reviews

- European Comics

- News

- Comics News

- Press Releases

- Columns

- Spotlight

- Digital Comics

- Webcomics

- Cult Favorite

- Back Issues

- Webcomics

- Movies

- Toys

- Store

- More

- About

By Leroy Douresseaux

April 17, 2007 - 16:05

|

Sometimes my Bin interviews and Q&A's have an agenda. Usually, that agenda is to encourage people to discover the work of a cartoonist that I think deserves wider recognition. This time the cartoonist I'm pimping is Richard Sala, a comic book creator and cartoonist who has been working for two decades. His expressionistic style mixes horror, humor, mystery, and whimsy, all with gothic flourishes. Many people compare him to Charles Addams and Edward Gorey. I use the shorthand - his comix are cousins of Tim Burton's films or even the works of Lemony Snicket, with whom he's collaborated.

The past year has been busy for Sala, as he's had two graphic novels published, and he has begun a new series for Fantagraphics and Coconino Press's Ignatz line, Delphine, a take on the Snow White fairy tale:

CBB: Whenever I write about your work, I dredge up so many names as influences (Charles Addams, Edward Gorey) or like-minded artists (Tim Burton), so who were your essential influences?

SALA: For an artist to be influenced by other artists and still develop his own style and point of view -- what happens is you pick up a piece of one artist and a slice of another and so on. You find those things in the work of other artists that speak personally to you. Ideally this happens when you're young -- and it happens naturally -- you recognize a kindred spirit or whatever. Then it may start as a planned strategy ("I want to draw like this guy"; "I want to write like that guy"), but as time goes on, after you've absorbed what you needed to, to feed your own creative impulses - and when it's only your own creative impulses that are driving your work -- then the work of your initial influences should ideally be visible in your art only subliminally or as an occasional glimmer.

|

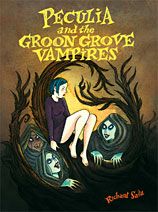

| Peculia and the Groon Grove Vampires - Evil Eye #13 |

So - yes -- I really loved Charles Addams' art and his point of view, but I didn't want to (and couldn't anyway) do gag cartoons. And I really loved Gorey's voice and his way with words -- but it wasn't in my nature to the draw the way he drew -- that very controlled way. Gahan Wilson is actually sort of a synthesis of those two -- he had that same dark-humored point of view and ghoulish artwork, plus he didn't only do gags (he did lots of amazing strips for Playboy and National Lampoon, for example). So, growing up I was crazy about all three of those guys. But none of them did traditional full-length

graphic novels or comic books. So my desire to create narrative comics came from somewhere else -- and I'd say it was my number one influence, especially concerning the way I learned to tell stories visually: Chester Gould's Dick Tracy comic strip.

I know it makes me seem a hundred years old to say that, but when I was little, Dick Tracy was on the front page of the Sunday comic section (in Chicago) and I got hooked at a very early age. It was the first thing I ever saved -- I cut out strips and put them in scrapbooks -- even before I began saving comic books. The Tracy strips from the 1960s and 1970s seem to get a bad rap sometimes compared to his earlier work -- but I was perfectly happy with them -- they were crazy and lurid. They had stopped being like police procedurals and instead were about -- well, to this day I'm not sure what those later strips were about! Good and evil maybe? Who knows? But you really never knew what would happen next. They could certainly never be in daily newspapers today -- not just because of the violence (which was gloriously over-the-top) but because in its twilight years it often appeared to flirt with becoming seriously unhinged.

A big hardcover collection of all the earlier classic Tracy strips came out some time in the late sixties -- and that became my bible. I read it hundreds of times. I didn't care too much about the character of "Dick Tracy" really -- in fact he often seemed to be just another weirdo in Gould's gallery of grotesques. What hooked me was the eccentric art and storytelling. The stories had lots of crosscutting in them, or jump cuts -- scene changes with no explanation of where you now were -- more than I remember any other

comic strips having at that time. So they had the feeling of cinema, but it wasn't cinematic at all -- they were very much hand-made and the creation of one single individual.

|

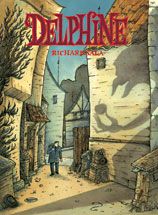

| The cover of Sala's entry into the Ignatz line: Delphine #1 |

I think that's why I didn't grow to be as crazy about mainstream comic books - I recognized the power of a single vision over a group of people, each perhaps watering down a little of themselves for the "good" of the whole. (There were exceptions of course). It's also why the big movie version of Dick Tracy couldn't do anything but fail -- it couldn't capture Gould's delirious artistry. People who have never immersed themselves in his universe think that Dick Tracy is just some iconic good-guy, like the Lone Ranger, but the stories were always more about evil than about good. Tracy himself only existed to clean up the messes made by everyone else -- and to keep the world from just crumbling into chaos. I wish they would have let the strip die with Gould, but other artists took it over -- different writers and artists -- and that only proved how unique and irreplaceable Gould's vision was.

So although many, many more things have certainly influenced me over the years -- especially horror and mystery movies of all kinds, for example, as well as my years in art school where I learned, unlearned and relearned lots of things that have made my art what it is -- if you boil it down to the essentials - to where I first had a glimpse of what I wanted to be able to do - it's probably Addams and Gould.

Aren't you glad you asked!?

|

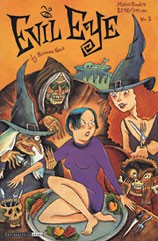

| Evil Eye #3 - the earliest issue you can still buy from the publisher. |

CBB: Two-part question: Part 1 - How would you describe your new series Delphine and how many issues will it run?

SALA: Delphine is about a traveler who arrives in a small town, located in the mountains and surrounded by a huge forest, looking for a girl he went to school with. Almost immediately he finds obstacles in his way and suspects that he has placed himself in the middle of something very strange and dangerous.

I had planned for the story to run six issues -- that may change to five issues. I'll know for sure by the time the third issue is done.

CBB: The advertising copy describes Delphine as a take on Snow White. If that's the case, what is it about Snow White that intrigues you as source material for Delphine?

SALA: Like a lot of people who are fascinated by horror stories, I'm also fascinated by folk tales and fairy tales. Tales by the Brothers Grimm, for example, still have the ability to get under your skin -- or maybe more accurately, into your subconscious -- if you read the real originals, that is, rather than any of the countless saccharine or watered-down versions out there. I often dip into them for ideas -- they contain so many archetypal situations. But, if you're a writer, you try to look at them in new ways -- maybe get a different perspective. In this case I thought it might be interesting to tell the story of Snow White from the point of view of "Prince Charming." The story has been told so many times, it's so familiar, that I thought this would be a fresh way to approach it -- to follow his journey to find her. But since this version of the story is set in modern times, the "prince" is merely a traveler, an ex-boyfriend. At it's core (no apple pun intended!) the tale by Grimm has all the elements of a horror story. And that's the territory I'm exploring in Delphine.

CBB: How did Delphine come to be part of the Ignatz line? Was it created specifically for that format?

SALA: I had really liked what I'd seen of the Ignatz line -- the art and writing, the high quality of the production. I wrote up a proposal and sent it to my publisher, Kim Thompson, who is releasing the US editions. He gave it his okay and told me to send it on to Igort in France, which I did. And, thankfully, I got the green light.

I have lots and lots of idea fragments scribbled down in notebooks that have piled up over the years and this concept may have been based on one of those -- you know: "man arrives in strange town looking for old friend." It's nothing new -- Bad Day at Black Rock is an example that just occurred to me -- but all the actual details were created specifically for this series.

I was nervous submitting it because I have tremendous respect for all the artists involved with Ignatz. Once it was accepted, I felt a real obligation to do the best work I could do. I don't want to let them down!

|

| Cover to Evil Eye #11 |

CBB: I've been reluctant to describe your work as "gothic humor." Do you think that's an accurate description of your work and why? In fact, is calling your comix humor accurate? (Lambiek describes your work as "horror noir").

SALA: I don't know if I'm the one who should be classifying or labeling my own work. Ultimately, it may matter more how readers perceive it or describe it than what I might call it.

It's tough, because sometimes I wish someone WOULD come up with a definitive label for what I do -- it might help me find a wider audience! I'm frequently lumped in with alternative creators or auto-bio-types more than with fellow genre creators, which is partially because most of my books have been published by Fantagraphics, which has long been regarded as a publisher of alternative comics (even though they now put out books like the Peanuts collections and Dennis the Menace and The [Pin-Up] Art of Dan DeCarlo and so on). And it's partially because I've tended to flirt with the kind of things you find just outside of the borders of genre fiction -- the places where Franz Kafka or David Lynch might go.

I've always made room in my world -- particularly in some of my earlier stories -- for the inexplicable, for questions that can't be answered. Maybe that's thrown some people. Then there's the fact that I enjoy putting humor in my stories, as you point out. Sometimes when the worst, most awful things are happening, I have a tendency to see humor in it -- I don't know why -- a defense mechanism of some kind, I assume. So I can see the world in a cruelly ironic and absurd way. I don't necessarily WANT to see it that way, but for some reason I do. Again -- I see a similar humor of the absurd in Kafka and Lynch. See -- there are reasons that some things are described as "Lynchian" or "Kafkaesque" -- because we don't really even know how to describe those two artists' work other than that it's work done by them. Does that make sense?

None of that helps in describing exactly what my work is, I guess. The best, most loyal fans I've ever encountered -- by far the kindest and most supportive -- have been horror fans. So, if anyone chooses to describe me as "horror" anything or "gothic" anything -- that's A-OK with me, because in my heart I'm a horror fan, too. There was just a review of one of my books in Rue Morgue Magazine that said my work was "as good as light horror entertainment gets." That was a descriptive phrase I'd never heard before -- I'm not sure I even know what it means. But it was a positive review, so who am I to complain?

CBB: When did you actively begin to work at or train yourself to become a cartoonist?

SALA: I tried so hard not to become a cartoonist. I spent six years in art school. I have a Master's degree in painting. I spent several years as a library assistant and applied to library school, which I saw as a way to legitimatize my bibliophilic nature (luckily I wasn't accepted). I spent many, many years as a freelance illustrator -- starting when I was in college and continuing through all my other work and schooling as an occasional way to make extra money until I finally became a full-time freelance illustrator from the late 1980s on.

All that because I tried to deny myself the pleasure of what I really truly always wanted to do -- be a cartoonist. I just couldn't believe my weird stories and strange way of drawing would ever have a place in the world of comics. But then I saw RAW, which was published by Art Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly in the 1980s. They published stories that were weirder and art that was stranger than mine. That's when I thought -- maybe I should give it a shot.

|

| Cover to Evil Eye #12 |

CBB: What led up to your decision to self-publish Night Drive and was that your first attempt at making comix?

SALA: It was, unless you count the issues I drew and stapled together as a kid. Also - when I was first at college I did some strips -- I remember they were inspired by Heavy Metal magazine and European guys like Druillet and Jean-Claude Forest. But they were kind of forced. It wasn't me. In art classes I was drawing portraits of characters from German Expressionist films, like [The Cabinet of] Dr. Caligari -- but I couldn't imagine that working in comics at that time. This was just before the punk scene exploded and after most undergrounds had died out, so at that time Heavy Metal and some of the later undergrounds like the Richard Corben stuff - that was about the only alternative to all the superheroes and barbarians and (God help us) funny animal comics that were popular at the time.

I always liked the old-time Golden-Age comics -- the cruder the better! -- and I always loved Jack Kirby -- The Demon was the very last mainstream comic book I continued to buy throughout high school -- even after I had a girlfriend! -- it's still my all-time favorite Kirby title. But by the time I was in college in the late 1970s, there just wasn't the kind of work out there that I could see myself being a part of.

I was actually trying to get work as a writer. I was sending manuscripts to the science fiction digests. I got some nice rejection letters -- they basically said, this story you sent is okay, but it's not science fiction. I was just sending them the kind of work that I'm still doing now -- you know -- sinister and creepy pieces heavy on the noir atmosphere with no spaceships or Martians in sight. I probably knew they wouldn't publish them. But I couldn't figure out where ELSE to send my stories!

Then, after I moved to the Bay Area to go to graduate school, I started to see RAW around -- and I realized there might be a place for someone like me in comics after all. So I did Night Drive and borrowed a thousand dollars to self-publish it. Then, since they had inspired me, I sent a copy to RAW. They wrote me back and eventually I ended up being in a couple of their later issues. That was incredibly encouraging!

CBB: Although you are published by Fantagraphics, which is basically an alt-comix or small arts publisher, I find much of your work to be certainly accessible to a wider audience outside of Direct Market comic book shops. Are you getting any indication of a broader audience coming to your work, even if the movement is slow?

SALA: Once again -- this is something that's hard for me to judge or control. Some days it feels like I'm making headway with sales and attention, other days, not so much. I knew all along that my work wasn't exactly geared toward huge mainstream success, so I'm grateful for what I do have. Certainly I've seen some progress in getting my work out there -- primarily because of the Internet. Now anyone with a computer can look at my art or purchase my books online, whereas before that experience had been limited to customers in about a dozen comic book stores!

|

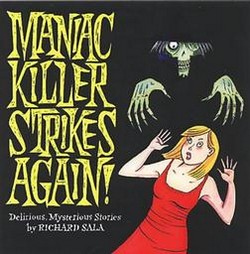

| A 2003 collection of Sala's early work |

CBB: You've been an animator. Do you see yourself making animated films again or do you prefer to focus on comic books and graphic novels?

SALA: I love books. I can't think of anything I'd rather do than make books. However, there's no denying the appeal of movies and animation. If the planets ever line up and the right project comes along -- you never know...

CBB: What does the future hold for Evil Eye, and what other works besides Delphine will be heading our way that you want to talk about?

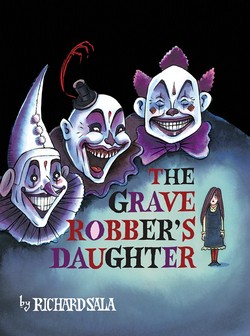

SALA: Ideally I would still like to put out at least one Evil Eye book a year. The first two, since the format changed from comic to graphic novel -- Peculia and the Groon Grove Vampires and The Grave Robber's Daughter - seemed to have done pretty well, so I'm psyched to do another soon. I've begun planning something out. Meanwhile, Delphine #3 is a bit more of a priority. I'm hoping that can be released by the end of this year. (Issue #2 has been turned in and is supposed to be out this summer). I also have another graphic novel I've been working on -- on and off -- for over a year. That's intended to be my first full-color graphic novel. But I can't say anything else about it until it's further along.

I also have stacks of older stuff that's long out-of-print or never been properly published, so one day I may put out another collection of odds and ends, similar to the book I did a couple of years ago called Maniac Killer Strikes Again! That was a fun book to put together -- it's some of my own personal favorite stuff -- so it would be cool to get chance to do another one of those. We'll see...

Most of Sala's work can be purchased from his publisher at their website, fantagraphics.com.

Visit Sala's site at http://www.richardsala.com.

The image for The Grave Robber's Daughter comes from barnesandnoble.com and the one for Maniac Killer Strikes Again comes from the site infinityplus.co.uk.