|

|

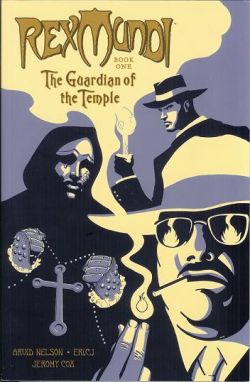

Fedoras and religious sorcery...where's Indiana Jones? |

In Rex Mundi Book One, Arvid Nelson introduces the reader to the mysterious and menacing world he created for the story. It’s 1933, but the Bourbon family still rules

The story opens when Dr. Julien Sauniere is visited by his friend Father Marin. A secret manuscript has been stolen from Marin’s library with no signs of tampering. Father Marin suspects foul play in the form of unlicensed sorcery. When Julien Sauniere finds the only other living person who knows of the document, she’s been horribly mutilated, strange writing inscribed all over her body.

As with his current series Zerokiller, Nelson has molded a thinking reader’s comic, complete with a strange and believable alternate history. Nelson’s world combines elements of Medieval, Enlightenment and nineteenth-century

Rex Mundi’s world is entertaining, but the reader wishes Nelson would incorporate his alternate history into the plotline more aggressively. In some chapters, he seems to separate Sauniere’s story from the alternate history, when a better blend of the two would make a stronger story. Nelson’s 1933 is a fascinating place that deserves a more integrated role in the story.

Penciler and inker EricJ, like Nelson, fashions an impressive world for his characters, but sometimes falters in drawing the characters themselves. He excels in moments of high tension, and his ability to make fear pulsate like a living organism makes Rex Mundi’s sense of dread all too real. He struggles when drawing common situations, and this problem makes the comic’s slow moments sag between the well-rendered action sequences.

Worth the money? I’d recommend finding a back issue, or current issue first, to get a better feel for the series. If it’s to your liking, you’ll be well rewarded by Rex Mundi’s consistent tone.

© Copyright 2002-2019 by Toon Doctor Inc. - All rights Reserved. All other texts, images, characters and trademarks are copyright their respective owners. Use of material in this document (including reproduction, modification, distribution, electronic transmission or republication) without prior written permission is strictly prohibited.