- Comics

- Comics Reviews

- Manga

- Comics Reviews

- European Comics

- News

- Comics News

- Press Releases

- Columns

- Spotlight

- Digital Comics

- Webcomics

- Cult Favorite

- Back Issues

- Webcomics

- Movies

- Toys

- Store

- More

- About

By Leroy Obama Douresseaux

July 13, 2008 - 09:57

|

In the third decade of the 19th century, Nat Turner (1800-31), an American slave of African descent, started the largest slave rebellion in the antebellum southern United States. He made “kill whitey” a reality long before it became at a fringe Civil Rights slogan. Born without a surname like other slaves, Nat became known by the name Nat Turner, taking on the surname of his owner. By the time he was captured (and later hanged), Nat and his fellow insurrectionists (freedom fighters?) had killed over 50 whites.

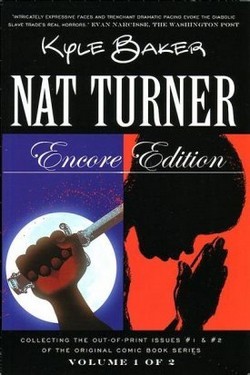

A few years ago, acclaimed cartoonist and comic book creator Kyle Baker (Why I Hate Saturn, Plastic Man) embarked on what he called a historically accurate comic book biography of Turner, who was also a popular religious leader among fellow blacks in the Southampton County region of Virginia where Turner lived all his life. Published as a four-issue miniseries in 2005 and 2006, Nat Turner was first reprinted in two “Encore Editions.” Nat Turner Encore Edition, Vol. 1 (2006) reprints Nat Turner #1-2.

The first time I read Nat Turner #1, I didn’t want to read anymore. This vision of the real-life slave turned insurrectionist was so potent that for me it was like a religious experience – one that I certainly didn’t want or need at the time. Add that to what I knew to be Turner’s fate, and I wasn’t sure I was ready to continue reading the rest of this series – although the first issue was, at the time, probably the most excellent comic book reading experience that I’d had in years.

Image Comics recently initiated a simultaneous publication of both a hardcover and paperback trade collection of the entire Nat Turner series, which has prompted me to go back and re-read it. Baker presents this graphic novel (the miniseries format was merely a way to serialize the novel) mostly as a pantomime or silent comic. The words in the word balloons are usually replaced by an image. This has a way of heightening the reader’s sense of what a vivid storyteller and speaker Nat Turner was when performing before a large audience of slaves. In this comic, the other slaves heard his words, but as potent as those words were, the slaves translated what they heard into evocative and moving images that reflected their experiences.

That’s what this graphic novel is about – the use of brawny yet simple images that convey the absolute fucking horror of the systematic destruction of a people and the enslavement of the survivors. That these people were enslaved not so much for their skin color, but because they would make the best slaves for the agrarian system in the Americas makes this no less evil.

The second issue, also reprinted here, begins the narrative’s focus on Nat Turner and his emerging life as a religious figure and troubled visionary. In this chapter, Baker offers a mixture of comic book panel illustrations and text pieces, text that offers us Turner’s own words. In this second issue, for the first time words match the potency of the images and combine to create an emerging Turner, offering the reader a better look at the man he would be. This is also a good way to carry the reader into the more violent and active second half of Nat Turner.