The Fifth Estate: Top Gun – Two Takes

By Eli Green

March 15, 2009 - 17:30

|

On Friday, March 6th, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) aired an episode of its investigative news show, CBC News: The Fifth Estate entitled Top Gun (click here to watch the full episode). The episode focused on the tragic story of Brandon Crisp, a 15-year-old Barrie, Ontario boy who ran away from home after a fight with his parents, over their confiscation of his Xbox 360 and games, and was found dead about three weeks later, from injuries sustained from falling out of a tree. The episode also discussed video game addiction and its relation to Crisp's story, and the industry in general. When we found out that the episode would be airing, our expectations were set as to what would be shown; the standard “blame the current popular media (in this case, video games) on society's ills” bend. We wouldn't leave things at that though. We watched the episode for ourselves and came to our own conclusions.

Some of the points discussed in the two different takes may repeat, but the opinions and analysis will likely differ.

Sean's Take:

Video game addiction has been controversial for quite some time; however most cases don’t turn out like the one with Brandon Crisp. CBC News: The Fifth Estate’s report on Brandon Crisp’s story, video game tournaments and overall addiction to the activity was titled Top Gun, to reference how these kids need to “kill their way to the top.” Gillian Findlay hosts the show as it was broken down into three main sections: Brandon Crisp’s story, a short look at Daniel Folmer’s story of battling video game addiction and interviews with a couple of representatives from different areas of the video game industry.

The show opened with scenes from one of the most popular first-person shooters on the market currently: Call of Duty 4. This too was the game 15-year-old Brandon Crisp had become addicted to. Young Brandon ran away from home last fall when his Xbox 360 was confiscated. His games were taken away because he had begun to play far too much. He played till 2 or 3 in the morning and even skipped school. When his father took away the console, he sneaked into their room and took it back. From there, it was taken away permanently.

Now would this be an addiction? Yes. He started this once he was cut from his hockey team at the age of 12. His attention was then put into video games on a full time basis. Before Brandon even brought up the idea of leaving home, would he still be classified as addicted? In my point of view, putting off everything else in the world in turn for more game time would show that he was. Now, I do enjoy playing games and spend a good portion of my free time with them, so I can relate to him a little in his choice of free time activities. However, there are always boundaries which can be crossed. Skipping school is indeed one of them.

The show brought up some reasons why he may have become like this. The obvious question is: where were his parents? When interviewed, they stated that they thought it was normal since “lots of boys like guns and war.” They also thought he was interested in something besides the gameplay, considering he was a “history nut.” However, I find it still a little odd that the parents didn’t act sooner, when Brandon would rush through dinner just so he could get back to his game. That, and his constant late night game time, on school nights, should have been a clear sign that he may have been too into his video games.

|

| Danielle LaBossiere Parr talks with Findlay about the industry and age ratings. |

Another segment of the show had Ms. Findlay interviewing video game company representatives, inquiring about the distribution of these types of games and what road blocks, if any, they have put in place so younger kids can’t get a hold of them. This portion of the program was integral because Brandon was underage when it came to the video game industry’s viewpoint. On every game box there is a mark called the ESRB rating. What this does is tell the buyer how old a person should be when playing this game. Call of Duty 4 is rated M for Mature; a rating that means the game is not suitable for kids under the age of 17. I agree with this rating for the most part. A young child should not be shown some of the intense violence and imagery that certain video games contain. However kids everywhere are getting hold of these games one way or another. Though, you are allowed to play them if you have consent from a parent or guardian above the age restriction.

From there, Findlay interviewed Daniel Folmer, who has a similar issue when it came to video games. Folmer's case was somewhat different though, as he admitted he had a problem. What made me so interested in Folmer's story was how he stated that he was clean from it. He noted that it took him a couple years to get to the point where he was only playing for fun again. He realised he had a game addiction when he would become incredibly angry when not allowed to play. He mentioned that he and his mother would get into intense arguments over allowing him access to his console. This would be a more physical manifestation of his addiction. He even said at points that he would get “the shakes” when not having played for some time.

This then brings up the argument of whether video games can, in some cases, be treated in the same way drugs are. Gary Direnfeld, known for his advice on the lifestyle television show Newlywed, Nearly Dead, states that:

“While video games aren't the same as drugs, they can produce a similar effect: a sense of euphoria and power plus an adrenaline rush that proves addictive.”

A statement I have seen several times prove itself true. We all have. If you have experienced online gaming, you have most likely come across the kind of people who take the game far too seriously. The ones who insist on yelling angrily into their headsets each time they are killed in game. Daniel stated that he would become upset when the people he shot at didn’t die. Though, every head shot he got, made him feel good.

|

| Gary Direnfeld - Social Worker |

So I would agree with Mr. Direnfeld. I would never call video games a drug. They don’t physically affect your body in a negative way, which is the main case here. But self control comes into play. As it does with everything one does. The phrase “too much of anything can be bad” is quite evident here. Another aspect that kept Brandon coming back was he was part of a team or “clan” as they are referred to online. When anyone in the clan had to go do homework or just leave the game in general, they would be ridiculed. The concept of peer pressure came into play. From here we can see that anyone willing to put this above some of the more important aspects in life (like your family and friends) does indeed have some sort of an attachment issue. This is mainly what it came down to with Brandon and Daniel. The only difference is that Daniel realized his problem and got help. Brandon never got to that point.

Findlay posed the question to another industry representative: Why do you make these games “too desirable” if they can have this kind of negative affect on kids? I found this quite an odd question to ask, and you could see the man did as well from his abrupt pause after her question. From a marketing point of view, having your audience play the game for an incredible length of time is good. They make money the more people play. A game company wants to make their games this enjoyable. I found Ms. Findlay’s question quite absurd. She was almost trying to put the blame of addiction on the company, which is something I disagree with entirely. As I stated before, this is all about self control. It was obvious Brandon Crisp lacked enough of this.

In the end, video games can not be blamed entirely for how they influence the people playing them. The industry has set procedures in place to try and keep games which are meant for older audiences away from kids. If parents buy their young children these violent video games, it was the parent’s fault for not being educated. You wouldn’t buy a new car before you learned anything about it. When it comes down to the way Brandon’s case was handled, I would put fault on both the boy and his parents. The parents are at fault because they should have acted sooner and been more strict. There were obvious signs that he was creating an unhealthy living arrangement around this game; they choose to just let him be. But the main fault was Brandon for not realizing what was happening and acting out in such an erratic way. No one forced him to play this game in an unhealthy fashion. He was addicted – we can all agree on that – but it wasn’t because the game was created in a way to have this outcome, it was because he didn’t have enough self control and responsibility when he chose to play it so much.

Eli's Take:

Predictable. It's one of the best words to describe this episode of The Fifth Estate. Top Gun dramatically opened with the music from the Halo 3 diorama commercial, showing a gamer playing Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare and soon switching to images of a Major League Gaming tournament before Gillian Findlay made her introduction to the story of Brandon Crisp. For the most part, I saw what I expected to in this episode; sensationalist journalism which specifically focused on only one area of an industry, generalized it and then tried to make it look as if that case was a standard thing that people exposed to that industry's product would do. There were some interesting additions to what was known of Brandon Crisp's story though.

|

| Steve and Angelika Crisp |

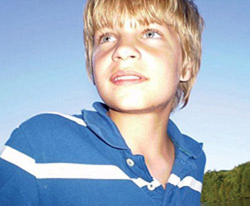

The first portion of Top Gun focused on the basics of Brandon's story; his receipt of an Xbox 360 and Call of Duty 4 in 2007, his introduced to online play by his friends in early 2008, how he became obsessed with the game between early 2008 and the summer, by which time his friends had moved on to summer jobs, his parents' worry over his constant play and their multiple confiscations of his system, and, finally, him running away, his disappearance and his death.

But while original reports on Crisp's story made it appear as if he was just a kid so addicted to video games that he simply had an irrational reaction, and ran away from home when he was told he wouldn't get back his system, there was far more going on behind the scenes. Further investigation, after his disappearance and death, found that Brandon was extremely involved, not just within the regular online Call of Duty 4 gaming community, but, quite specifically, the hardcore tournament gaming community. As it turned out, and as his parents noted, Brandon was the kind of person who was driven to become the best when he excelled in a particular field. And, unbeknownst to his parents, Brandon actually working his way to becoming a full fledged tournament gamer. According to his profile statistics and people he played with, Brandon was playing within the top ranks of the tournament community. So what does this mean?

According to Gary Direnfeld, a social worker who, along with dealing with numerous other family related issues, has had parents come to him asking for help relating to their kids and video games, “The parents are at their wits end”. Direnfeld says that the parents who come to him don't know how to deal with their child's attachment to video games, telling Findlay, “They're pulling out their hair. They don't know what to do. They don't know how to limit their son. And they get held hostage by the backlash from their teenager, when the teenager says, 'You can't do that to me'. They're scared”. It appears that Steve and Angelika Crisp were in a very similar boat with Brandon. It also certainly seems as if their only solution to a recurring problem, in this case, Brandon's excessive gaming, was to do the same thing over and over again, regardless of whether it worked or not.

|

| It took Daniel Folmer a few years to recover from video game addiction. |

Daniel Folmer, a gamer who fought and overcame video game addiction, knows the feeling and the situation all too well. Before he realised he was addicted to video games, Folmer would “get in pretty intense arguments” with his mother over his video game use. “I felt physically compelled to play,” he told Findlay, “And every time I couldn't play, I was angry, I was upset”. It took him years to recover and return to the point where he was just playing for fun. While demonstrating the gameplay in Call of Duty 4 for Findlay, Folmer explained how he felt when he first started playing. He would get “chills”, or what many of his friends call “the shakes”. He would, and still does, feel anger when he would shoot an enemy in the game and the enemy didn't die. When he made the kill though, it felt good.

Then Folmer mentioned one of the things that makes video games so enjoyable, the sense of achievement and reward for progressing in games. “What's even weirder about it is that there's achievement, experience involved,” he said. “You kill 50 people, you get to level 2. You kill 100 people, you get to level 3. You kill 200 people, you get to level 4. And as you level, you're accomplishing things and getting rewards, and your brain is telling you, 'Okay. I got a reward. I love this'”. This works similarly in less violent or non-violent video games, where the more objects of a particular type you collect, the more you have achieved.

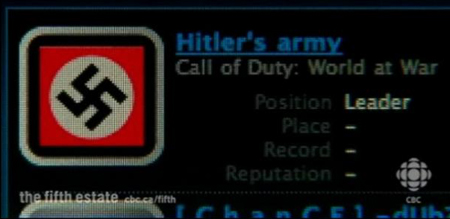

Things then took a tangent to the way kids talk and act when they play online. For gamers, hearing smack talk while playing online is nothing new. For an investigative journalist though, hearing the kind of things young kids say, and seeing the kind of clan names that you can find online (like Hitler's Army), was a shock. Findlay says, “In this parentless universe, where players talk to each other over the Internet, you can be whoever you want to be, and act in ways you'd never get away with at home”. If that's true though, this “parentless universe” must exist outside of all time and space, because, at some point, parents must, at the very least, hear the kind of language their kids are using while online. And whether a parent knows their child is online or not, if they feel that kind of language is inappropriate, they would be doing something about it. This all lead to the question of “Why are kids playing these games in the first place?”. Brandon's own friends, also 15 years old, play games like Call of Duty 4 and Gears of War 2, both of which are rated M for Mature (ages 17+), regularly. They also purchased each of those games by themselves, something they shouldn't have been able to do, based on procedures the industry has attempted to get retailers to cooperate with and put in place.

|

| Yes, that's a real clan name. |

David Walsh, a child psychologist, was one of the people who pushed to have the Entertainment Software Rating Board's (ESRB) ratings system adopted as a standard for the North American video game industry. He understands that when the ESRB rates a game M for Mature, it isn't appropriate for younger teens or kids, and parents should understand that. But kids are still getting their hands on the games somehow. Walsh suggested that kids are getting the games on their own, but Danielle LaBossiere Parr, a representative for the video game industry in Canada, told Findlay that, most often, uneducated parents are buying them, and, even if their kids get the games through other means, those parents are still allowing their kids to play the games, even if they are inappropriate. As someone familiar with the retail sector of the video game industry, I can say that Parr is quite right.

Most often, parents do not take the time to educate themselves with the video games their children are playing, or asking them to purchase. Many parents ignore the ESRB rating on the front of the box and the content information on its back. As they do with television and movies, parents will often leave the electronic babysitter to do its job, and the kids will just naturally know what is right or inappropriate for them, as well as when enough is enough.

Finally, Findlay moved onto the last piece of the “puzzle”; video game tournaments, and the pressure tournament gamers and gamers on teams feel driving them to play, from teammates and the possibility of sponsorship deals. This portion of Top Gun included interviews with the AMP Energy Pro Team, their manager, Bruce Wayne Yip, and the CEO of Major League Gaming, Matthew Bromberg. This portion also brought to light the very thing that was likely the driving force behind Brandon Crisp's gaming addiction; his drive to become the best, and the acclaim that would come with holding a top gaming title.

|

| Thousands crowd around an MLG tournament event. |

The world of tournament gaming is an interesting one. E-sport is a spectator sport unlike any other, because it is the only one that takes place outside of the real world. Players make their mark in number of kills, instead of hits, goals, runs. The games most commonly played at Major League Gaming tournaments are first-person shooters, and the players often range from young teens to guys in their late twenties or early thirties. It has emerged as a whole new sport, and the players, as a whole new type of athlete – e-athletes. Tournaments are held at conventions, but are on their way to becoming their own full fledged events. They are already broadcast over the Internet, and have even been shown on networks like CBS and The Score. Players don't just play for titles and the money that comes with them, but the chance to be sponsored as well, just like the AMP Energy Pro Team, which is sponsored by Pepsi.

While there is nothing wrong with major corporations sponsoring events and players, or even advertising at events, just like they do at regular sporting events, Top Gun raised a serious issue in the way corporations like Pepsi are involved in gaming tournaments. At Pepsi sponsored events, AMP is handed out indiscriminately to young gamers. A high energy drink like AMP is not meant to be consumed by kids, especially not at the levels they are often consumed at these events. This is a separate but crucial note. Pepsi's involvement in the video game tournament circuit had nothing to do with the episode overall, but was simply something extra for The Fifth Estate to go after.

What really happened here?

The case of Brandon Crisp, tragic as it was, was one that could have been avoided. Due to the unfortunate stigma associated with video games, Brandon's parents only saw his excessive gaming as a problem to be dealt with, not something to be discussed or to involve themselves in. Rather than educate themselves on his situation,

|

| Brandon Crisp |

Brandon had also made poor decisions of his own. Instead of trying to tell his parents what he was working towards, at any point, he simply kept playing and fought with his parents when they confiscated his system. He was so addicted and driven to win that he was blind to his problem, and to his parents worry. When that fateful day came, he made a completely irrational decision and ran away. And his parents made things even worse by calling his bluff. This was simply a case where there was absolutely no communication and no compromise.

What makes things even sadder, especially in the way The Fifth Estate portrays tournament gaming and gamers in general, is that, had Brandon still been taking part in mainstream sports (he used to play hockey, but his father took him out because his small stature was holding him back from advancement), his obsession and drive would have been considered a good thing. When looking at the amount of training time the AMP Energy team puts in during the average course of a few months (over 800 hours combined), Findlay says that amount of time “reveals what appears to be to us some pretty unbalanced playing”. Would Findlay say the same of mainstream athletes training schedules? What if Brandon had been on the ice or, in the summer, out on the street, wearing himself out to become a better hockey player? What if he was driven to become an NHL All-Star? Would his obsession have been praiseworthy then?

When it comes down to it, what makes e-sport so different from regular sports? The athletes, or in this case e-athletes, involved are either playing or training all year long, to become the best. Their young fans look up to them and want to become like them, hoping to, one day, also play the games they love for large sums of money, whether from sponsorships or prize money. The age of players entering the sport are getting younger and younger. Heck, they even, supposedly, have their own performance enhancing substances (I'm looking at you AMP, Red Bull, Bawls and others). E-sport is a more mental sport, like professional chess, poker, crosswords, Scrabble, Boggle, etc. The only difference is that, because of the games involved, e-sport has a lot more action and is therefore more exciting. E-sport simply hasn't been accepted as mainstream, so it is stigmatised and, thus, looked down upon.

What about the fact that kids are getting their hands on and playing games that are clearly inappropriate for them? This is a multifaceted issue.

|

| The Entertainment Software Rating Board's ratings system |

The mainstream media chooses to lay the blame on the video game industry and the retailers for making it easy for kids to acquire M rated games, saying that kids can simply purchase the games by themselves. In truth, the video game industry in Canada, with the cooperation of major Canadian retailers, has specific procedures in place to make sure that kids can't easily purchase M rated games. Retailers like Toys'R'Us, Best Buy, Future Shop and EB Games are just some of the retailers in Canada, which sell video games, that have specific policies against selling M rated games to teens under the age of 17. Some of them even require their employees to sign contracts to make sure they adhere to those policies. Video game sales associates will often have to check photo id to confirm that the buyer is of age to purchase that game.

That said, the system isn't perfect. Sometimes an associate will ignore the policies, only to receive severe repercussions after the fact. Other times, the retailer involved is a smaller one that does not have any such policies. Most often though, uneducated parents, and sometimes grandparents, are the ones who purchase these games for their children. Parents don't take the time to educate themselves about the games their kids are playing, or they don't care. When Findlay asked Angelika Crisp what she thought about Call of Duty 4 when she first saw it, she sighed and said, “Well, lots of boys love guns and shooting and war,” clearly resigned to the “fact” that since “boys enjoy violent things”, it would be alright for Brandon too. She simply did what most parents do; shrugged it off. Unfortunately, that is essentially an admission that the parent believes that game is, indeed, appropriate for their child, regardless of the level of violence, blood, gore or other adult content. In actuality, it was alright for Brandon, as the level of violence in the game was not the issue at hand. His addiction stemmed from other issues, including pressure from teammates and his drive to become a top ranked player.

What about the fact that the games and tournaments are made to be so enticing? As far as the games go, what's the point of creating a game if nobody is going to want to play it? The same goes for tournaments, and those require endorsements from either a parent or guardian. And if a parent, or in the case shown in Top Gun, a grandparent, feels that their child/grandchild can handle it, then that's up to them. It is also up to them to manage their child/grandchild's training time.

|

| Time and training pays off for this tournament team. |

Finally, let's say that, even with all the procedures in place, a young player still acquires an M rated, online-enabled game, his/her parents don't feel that it's inappropriate, but they don't want him/her playing in online tournaments. Online subscription services like Xbox Live usually require parental consent in order to play, but that doesn't mean there aren't ways for kids to get around the system. Kids know how to use today's technology quite well, and if they really want to play online without permission, they can usually find a way. The only way parents can actually be sure their kids are “staying out of trouble” is to actually get involved and be parents.

It's time for the mainstream media to stop picking a scapegoat of the day and focus on the real issues. Parents need to be parents, and actually take responsibility for the things that happen in their households. Sometimes, even when precautions are taken, bad things can happen. But those situations are actually quite rare. It's time to stop looking for something to blame, and to work on preventing this kind of thing from happening again.

Related Articles:

Top Gun: Maverick

Top Gun (1986)

The Binquirer, August 21 Edition: Sergio Toppi passes away, Joe Carnahan moves on to Nemesis, James Gunn eyed for Guardians, and much more

The Fifth Estate: Top Gun – Two Takes

New Top Gun Game Nintendo DS