Pulp Culture, Part 4: From Pulps to Comics

By Philip Schweier

August 6, 2006 - 05:45

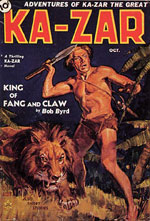

Heroes come in various forms. In the age before comics, they usually came in a magazine with a dramatic cover, featuring a fantastic setting with danger looming. Sometimes it was another planet, or maybe it would be the heat of battle with death on every side. Only one thing was certain: in the end, the hero would triumph. The variety of genres tapped into wider audiences, and gave birth to heroes to suit every taste.

|

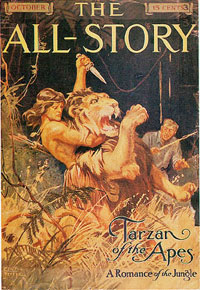

A prolific writer in the fields of fantasy and adventure, Tarzan’s creator, Edgar Rice Burroughs (ERB) first foray into fantasy fiction was A Princess of Mars, in 1912. His tales of Mars were later adapted to comics form, first from Dell in 1941. His comic book adventures were few and far between, perhaps overshadowed by his more successful literary sibling, Tarzan. The King of the Jungle went on to star in 24 novels written between 1912 and 1950.

First drawn by Hal Foster in 1929, he became one of the most popular stars of the funny pages, later illustrated by Burne Hogarth, and then Russ Manning. In comic books, he has starred in several ongoing series from all the major publishers. He made his comic debut in Dell’s Four Color Comics in 1947, leading to his own title a year later. Dell later

|

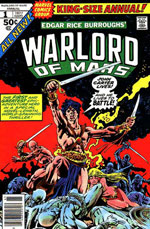

In 1971, when DC Comics acquired the license to many of ERB’s creations, John Carter, along with other Burroughs creations such as the Pellucidar and Venus stories, were featured as back-up stories published in Korak, Son of Tarzan.

Six years later, when the Burroughs properties moved to Marvel Comics, John Carter graduated to his own title that lasted for two years, as did its Tarzan title. Since then, the ape-man’s comic appearances have been sporadic, most notably from Dark Horse Comics in the late 1990s.

|

Another fantasy legend Marvel would resurrect from the pulps was Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian.

|

| At the age of 30, Conan creator Robert E. Howard tragically committed suicide. |

Despite the success of characters making the transition from printed pulp page to feature film, not every character enjoyed such movie stardom. Two of the most popular, Doc Savage and The Shadow, were introduced to new audiences when republished in paperback form in the 1960s, but the movies – released in 1975 and 1994 respectively – were box office disappointments.

The Shadow magazine from Street & Smith debuted in April 1931, feeding off the popularity of The Shadow radio program. Walter Gibson, under the pen-name Maxwell Grant, wrote 282 of the 325 stories published between 1931 and 1949. Street & Smith followed up The Shadow’s success with Doc Savage, debuting in March, 1933. Most of his 183 adventures were written by Lester Dent, under the pen name Kenneth Robeson.

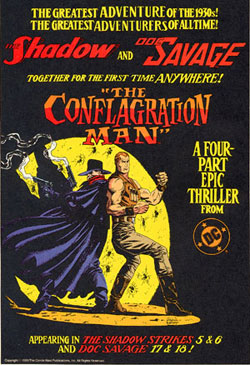

Street & Smith published several issues of The Shadow comics beginning in March, 1940. Some featured Doc Savage in backup stories before being launched in his own four-issue series. A Shadow newspaper strip was also attempted, but failed to find an audience. In 1964, Archie Comics attempted to revive him, but strayed form the original concept by giving him a blue and green skin-tight costume. The title lasted only eight issues.

In the early 1970s, The Shadow made another foray into comics. DC published adventures of The Shadow, written by comic book legend Denny O’Neil. Mike Kaluta, who has been identified with the Master of Darkness ever since, was a young, ambitious artist illustrating the adventures. Despite a well-received interpretation of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Carson of Venus stories, he was still new to the comic book format, and unaccustomed to the demands of a full-length monthly title. He began to fall behind in his deadlines, eventually leaving the book halfway through its 12-issue run.

|

Gold Key Comics attempted a Doc Savage title in the 1960s, but it was Marvel who seemed to have the most success. It began with a full-color comic series which ran for eight issues featuring adaptations of pulp novels. After the 1975 feature film starring Ron Ely, Marvel launched a black & white magazine of new original adventures. It also ran for eight issues, and was very much in step with the original stories from the pulps.

|

The pulp-like comic The Rocketeer and its sequel, The Rocketeer: Cliff’s New York Adventure, both featured characters that may or may not have been Doc Savage and The Shadow. Though never mentioned specifically by name, specific similarities make it obvious to longtime fans.

|

Dark Horse Comics then released an intermittent series of Shadow comics, some produced by fan favorite Mike Kaluta. In 1995 Dark Horse published The Shrieking Skeletons, another union between The Shadow and Doc Savage. Doc would go on to star in additional stories published by Millenium Comics in the 1990s.

|

It would be 1997 before the Man of Steel would encounter the Man of Bronze, and even then only as a vague figure in a darkened alley, but to fans the reference was obvious. Superman, in many ways inspired by Doc Savage, shared much in common with his pulp counterpart. Both were actually named Clark. Both had young cousins who would share some of their adventures, and both had an arctic hideaway known as the Fortress of Solitude, in which to retreat from the demands of their respective careers.

In 1991, The Spider made his first appearance in comic book form in a three-issue miniseries from Eclipse. It was successful enough to warrant a second turn a year later. It would be ten more years before his next appearance in The Spider: Scavengers of the Slaughtered Sacrifices from Vanguard Productions. Set in modern times, it was produced by long-time mystery collaborators Don McGregor and Gene Colan.

Praise and adulation? Scorn and ridicule? Email me at philip@comicbookbin.com.

Related Articles:

Pulp Culture, Part 4: From Pulps to Comics

Pulp Culture, Part 3: What's Black & Bronze and Read All Over?

Pulp Culture, Part 2: An Overview

Pulp Culture, Part 1: Copyright or Copy Wrong