Howard Chaykin: Back to the Drawing Board

By Philip Schweier

March 13, 2006 - 13:51

|

It was 2000, and Chaykin had just come to a parting of the ways with his last television show, the syndicated Mutant X. "It was a great job, a good ride. I learned a great deal, I had a great time, and I finally started working myself into an early grave. After I left the show I dropped 35 pounds, I started sleeping, and my life just got easier." The time seemed right for a full-time return to comics.

"I hadn't drawn in ten years,” says the seasoned comics creator. “I'd done some individual pieces here and there, but I hadn't really done any work of volume, and I discovered to my surprise and delight that my chops were still in pretty good shape."

Born in Newark in the early 1950s, Chaykin wanted to be a cartoonist since discovering comics around the age of four. He managed the feat by apprenticing himself to an acknowledged master in the field, Gil Kane.

“Everything I know I learned sitting and watching television with Gil Kane,” he says. “I'm serious. I didn't do anything. I was his go-fer, and the fact of the matter is it was the best learning experience I ever had. Gil Kane taught me everything. He taught me how to be a professional.”

He also apprenticed himself to Neal Adams and Gray Morrow, but it was Wally Wood who offered him his first published work. "I penciled Shattuck, a western strip for Wallace Wood to ink for the Overseas Weekly, a newspaper for sale to the military only."

Chaykin’s first job in mainstream comic books was in DC Comics' romance titles, a genre that soon died out. “The guys who edited them were failed book editors, and the guys who replaced them were comic book geeks. So they basically threw away the idea of girl readers, which really pissed me off, because I like girls.”

In the early1970s, super-hero comics were being done by men a generation older. “The Marvel Bullpen in those days was old guys,” he explains, “ And most of us were EC Comics fans or pretentious illustration fans, and came out of an entirely different world view. We all assumed – and this is not a joke – that we were the last generation of comics talent.”

Of his generation of comic book creators, he feels few of his colleagues were suited for drawing costumed crime fighters. "Rich Buckler was the most super-hero-appropriate character in the bunch," he says. "(Bernie) Wrightson was doing the horror and mystery stuff, (Mike) Kaluta was doing the same. (Walt) Simonson came in shortly after I did, with a science fiction portfolio. So none of us were really prepped to do super-heroes.

“All of us had grown up on that material, but by the time we'd become professionals – and I'm speaking for myself, and fairly certain I speak for most of those guys – we were interested in a wider range of material. I did pulp fiction, and science fiction, sword & sorcery. I was just testing the waters on everything I could get."

In 1972, DC Comics launched Weird Worlds, a science fiction/fantasy comic showcasing other characters created by Edgar Rice Burroughs, the creator of Tarzan. These secondary properties failed to find an audience. Before the book was eventually canceled, editor Denny O'Neil offered Chaykin his first taste of creative carte-blanche. His concept, Iron Wolf, led to seminal versions of ideas that would eventually be found in much of Chaykin's work. He infused it with "themes of romantic honor tempered by ironic detachment, played out against a background of galactic empires and brightly painted starships" – Howard Chaykin, from the Iron Wolf reprint, 1986.

|

Putting Atlas behind him, Chaykin continued to toil in the trenches of the comics industry, doing fill-ins on such titles as DC's Weird War. At Marvel, he and Len Wein collaborated on Dominic Fortune, another pulp-style character. They also put their heads and talents together for Gideon Faust, a Victorian era sorcerer published first in the pages of Star Reach, an independent sci-fi anthology comic, and later in Heavy Metal.

|

Chaykin was chosen to illustrate the Marvel Comics adaptation of the film. After a meeting with George Lucas in Burbank the year before the movie was released, Chaykin walked away with a box of 4,000 stills and a portfolio of conceptual paintings by Ralph McQuarry. "The stills were incredibly dead an inert," he explains. “They looked like a high school science project. What freaked me out when I saw the film was it ended up looking like the McQuarry paintings, and that was the most profound effect, that they managed to do all the work in post. It's a tribute to what was done to that film after it was shot."

Of course nobody had any idea the phenomenon that Star Wars would become. "Had I known, I probably would've worked harder on it. I still haven't gotten over the resentment of the fact that it existed in the pre-royalty times, so I got chump change for those books.”

|

However, the effort wasn’t as rewarding as expected, and he continued moving from project to project, such as DC’s World of Krypton mini-series, and another Marvel movie adaptation, James Bond: For Your Eyes Only. “I had to support myself elsewhere until I had a big screaming match with one of the mainstays with one of the major companies."

Driven out of comics for two years, Chaykin made a living by doing covers for Western and romance paperbacks. However, the national economy dipped dramatically in the early 1980s, coinciding with a developing conservatism in paperbacks. Publishers turned to other talents such as Pino and Elaine Dewillow. "It was the year of the bodice-ripper. I was doing fairly graphic stuff, and more influenced by Bob Peak and David Grove, and those guys."

|

|

"I make no secret of the fact that I'm a left-leaning kind of guy,” he says. “Unfortunately unlike a lot of my fellow left-leaning freres, I also have really complex ideas about multi-culturalism, and I'm profoundly patriotic, because I don't feel the right has any right to hijack patriotism, although they've done a fabulous job of it.”

Former First Comics editor Mike Gold regards Chaykin to be one of the most prescient comics creators since Steve Canyon creator Milton Caniff. “Every Chaykin reader who followed our culture, our technology and our politics for the past two decades is constantly suffering from deja vu.”

American Flagg! was just the sort of huge success any start-up company hopes for, but the arduous task of writing and drawing a monthly comic book took it’s toll on Chaykin’s health. After two years, he turned the art chores over to others; a year later, he left altogether.

A more relaxed schedule in the mid ‘80s allowed him to generate an enviable variety of projects. He created two additional graphic novels for First Comics centering on the post-modern world of Times(Squared). Featuring Runyonesque characters based on his own family, the books are among Chaykin's personal favorites.

|

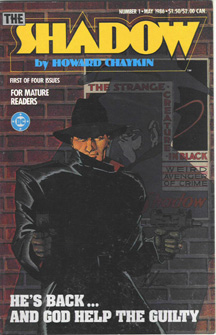

Chaykin’s version also imbued the hero with what today are considered unappealing character traits. "The Shadow is a man of the '30s, and in my version he's a man of the '30s running around in the '80s. Men of the '30s had certain attitudes."

Specifically, a certain amount of chauvinism, a trait which Chaykin defends as the nature of the beast. “We are a society that is constantly victimized by presentism. You've got a contemporary culture doing period material that imposes contemporary ideas on period ideas. So when I do period work, I try to convey period sensibility, and buyer be damned. And I'm frequently damned by the buyer because they want presentism, and they can find it elsewhere."

He then wrote and illustrated two mini-series for DC – Blackhawk and Twilight. Featuring the art of Jose Luis Garcia-Lopez, the latter instilled more realistic – and sometimes less pleasant – human qualities to DC's stable of science fiction heroes.

During this time, Chaykin returned to American Flagg! When the series concluded a year and a half later, he found new avenues for his work, most notably the controversial Black Kiss, an erotic thriller published by Vortex in 1988.

While major companies might have loved to have Chaykin on staff, he continued to eschew super-heroes. "You know, when you start giving a guy super-powers, my own innate goofiness comes in. I always felt the stuff that (Harvey) Kurtzman did, the Super-Duperman, the Plastic Sam, was closer to the way real people would behave. I believe that super-heroes should have feet of clay to bring them down to size and to make them more fun to be surprised by.

"One of my favorite comic books is that last Superman story that Alan Moore wrote. But I have no idea where to begin writing Superman because there's something, for me, so innately goofy about this guy. He's huge, he's all-powerful. Y'know, what if God and Superman had a fight? Superman would probably trip Him, so I can't imagine writing Superman."

Despite his disinterest in the super-hero genre, Chaykin is fascinated by Batman. "Batman is an allegedly normal guy who, if you really look at the subtext of Batman, he's a guy who had a bad day when he was eight years old. Since then he's been justifying the idea of going out and beating the living shit out of criminals dressed up as a bondage guy, and I'm fascinated by that. I think it's an amazing idea and I love taking a character and playing with him. It's why I've always done Elseworlds."

|

Another story, the three-issue Flyer published in Legends of the Dark Knight in 1991, is noteworthy as it was illustrated by Gil Kane, Chaykin’s former mentor.

Regarding Batman as a guy who is completely and totally his own self-product, Chaykin, like an actor searching for character, chooses to look under the mask. "I've always been much more interested in Bruce Wayne than Batman. Bruce Wayne's a really interesting guy. I want to do a story about Bruce Wayne involved in an Enron-type scandal, and Bruce Wayne at Bohemian Grove. It's where all the rich republicans and celebrities go up in Northern California and run around naked. You know, ‘Eliminate rage,’ and they dance naked around a bonfire. I want to see Bruce Wayne doing that."

Stumbling into television, he managed to find the financial success for which he was searching. "It was whore money,” he says shamelessly. Cultivating a television career throughout most of the 1990s, he worked on such shows as The Flash, Viper, and Earth: Final Conflict. “I started out a rung above the bottom (staff writer) and finished a rung below the top (executive consultant).

During his tenure in television, Chaykin continued to do occasional comic book projects, such as Power & Glory for Malibu Comics’ Bravura imprint. The story of a costumed hero manufactured by the American government, he describes it as " Broadcast News with super-heroes."

In more recent years, Chaykin, with writing partner David Tischman, scripted a number graphic novels and mini-series for DC comics. An ongoing series from Vertigo, American Century, ran for two years.

His television days behind him, Chaykin has returned to comics with fresh interests and renewed sensibilities. "I'd always been an anal structurist in every sense of the word. I'm a great believer in order and geometry, and for some ungodly reason, and I have no idea where it came from, I developed a jazz musician's improvisation, a lack of fear about not knowing exactly where I was going with an idea, which is a very new idea for me. It's brand new.

“I try to reinvent myself every five years. My stuff looks pretty much the same, but there's also stuff added to it, because I find myself getting too rock bound and conservative, so I end up throwing stuff out and trying something new. I mean, I've had a lovely career, but the truth is, it's been different every time and it's what keeps you young and fresh.

“I'm really lucky to have the work that I've got to do. I'm having a great time, because a lot of guys my age are sort of stultified and atrophied in their abilities and in their attitudes toward the material. It's a seven-day week, and I put in a minimum of 65 hours a week, and I'm not making nearly the amount of money I used to make in television, but I'm a lot happier.”

Chaykin shows no sign of letting up. Leading up to his drawing duties on Hawkgirl, Chaykin has done several covers for DC Comics, as well as a couple of limited series, one featuring a new take on the Challengers of the Unknown, the other his original story, City of Tomorrow. He also wrote Legend, a four-issue adaptation of Philip Wylie's novel Gladiator, with art by comic book veteran Russ Heath.

He is also currently working on a prequel to Black Kiss, as well as a personal project, Midnight of the Soul. Chaykin describes the book as a transliteration of the Greek myth of The Journey through a single 12-hour experience in a guy's life. “It's about a guy who is mortally wounded during the liberation of the death camps who's carried around a belief system that he's supported for five years through addiction to morphine and cheap wine. In this 12-hour period, where for the first time in five years he hasn't had a drink or a drug, he begins to learn that his memory is a screened memory, and it's all a lie, and things begin to evolve and change. By the end of the 12 hours his life is changed dramatically. It's violent, it's funny and it's very, very dark."

Both writing and drawing, he's danced around the idea of self-publishing the project. "It's come close to being published by various companies but it's something I really want to control. It's personally derived, there are metaphors from my own life in this job but in a world where super-hero comics are held in the regard they are, this is not an easy sell."

Despite such challenges in the comic book world, Chaykin feels very lucky. “It's an absolutely fantastic way to make a living. I work in sweats and a t-shirt and a four-day beard. I look like a homeless person, and I love my life, and I'm real proud and happy.

"One of the things about my life and my career I've always said is I am absolutely blessed."

(Portions of this story appeared in BACK ISSUE #10, May, 2005.)