Gorilla My Dreams: Tarzan of the Comics

By Philip Schweier

March 13, 2006 - 09:17

|

Burroughs, unlike most authors, saw himself as an entrepreneur, whose product happened to be fantasy fiction. Ever the businessman, the author exploited his creations in every way imaginable. Tarzan’s name and/or likeness appeared on all types of products, from clothing to household goods. In 1943 more than 3 million loaves of Tarzan bread were sold. There was even Tarzan brand gasoline.

Probably Tarzan’s highest profile endorsement was in 1928, when the community surrounding the author’s San Fernando Valley estate petitioned the federal government for a post office. The writer gave permission to name the town Tarzana. Burroughs then subdivided his 540-acre ranch to build more homes and businesses.

In January, 1929, Tarzan broke new ground by being the very first adventure newspaper comic strip. Until this time, the daily funnies were, appropriately enough, humor-oriented. It was a gamble for Metropolitan Newspaper Syndicate, but within a few years others soon joined in with ongoing strips such as Dick Tracy and Buck Rogers.

Harold Foster was the artist who launched the strip, but stepped down after the first adventure had run its course. Rex Maxon took over, but in 1931, Foster returned to illustrate the Sunday strip, while Maxon continued working on the daily adventures.

|

During this time, the ape-man invaded comic books, beginning with a handful of anthology titles such as Tip Top Comics and Comics on Parade. Published by Metropolitan Newspaper Syndicate, the Tarzan feature was primarily re-prints of the newspaper strip.

|

However, fans could console themselves that after three years, Burne Hogarth was returning. The artist came back with a fresher perspective, and a renewed enthusiasm, enough so to work on both the daily and Sunday features. It proved to be a heavy workload, and he was aided by a handful of assistants before giving up the daily strip. Eventually, the Sunday strip also began to show signs of inconsistency, as much of the work was being done by Hogarth's students from the New York School of the Visual Arts. Among these were future comics legends Al Williamson, Wallace Wood and Gil Kane. Hogarth left the strip entirely in 1950, and Bob Lubbers took over until 1954 when he was replaced by John Celardo.

In 1961, a small controversy launched a period of revival for Tarzan. A teacher in Downey, CA removed Tarzan from the bookshelves of the school library, amid concerns by parents that Tarzan and Jane were living out of wedlock. But Burroughs fans rallied to the cause, clarifying that the jungle couple were indeed married in the books, and that while a wedding may not been portrayed in the movies, who is to say that it didn’t happen off-screen?

|

During this time, Robert Hode, the vice president and general manager of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc., began looking for viable outlets for Tarzan. Ballantine Books stepped forward, releasing legitimate copies of the original stories at the rate of 10 per publishing season. While sales were slow at first, by the time all 24 books were published, they were once again bestsellers on the paperback market. Later editions featured covers by popular artists Neal Adams and Boris Vallejo.

Dell eventually eliminated its comic book publishing, and Gold Key took over the property beginning in 1962. Its efforts, adhering more closely to the books, were better received by the growing number of Burroughs fans. The publisher also launched a companion title, Korak, Son of Tarzan.

|

In all his comic incarnations, Hode had always insisted that ERB, Inc. retain ownership of the material, granting it exclusive reprint rights. For the company, it was extremely beneficial. Gold Key put up the money to pay the writers and artists, and handled distribution. Burroughs, Inc. was able to keep the negatives for reprinting in other markets.

By 1972, Gold Key was interested in getting out of the comic book market, and Hode was running out of material for the overseas audiences. While Manning’s work had noticeably raised the level of quality, it also made some of the more mediocre work that less appealing. So Hode proposed hiring its own creative staff to generate new comic book adventures. All he needed was a distributor.

|

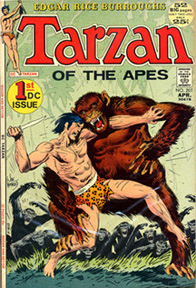

Though it is common today to re-launch a series beginning at #1, that is a more recent practice. DC chose to build on the momentum and numbering system already established, picking up with issue #207. However, publisher Carmine Infantino had his own artist in mind, rather than ERB, Inc.’s choice of Russ Manning.

Joe Kubert was a comics veteran, and a new breed of editor at DC, having built his career as an artist rather than a writer. So when he was offered a chance to not just draw, but write and edit one of his boyhood heroes, he was happy to take the job.

He began with a four-issue adaptation of the first story, Tarzan of the Apes. Its sequel, The Return of Tarzan, soon followed. He adapted several of the original novels written by Burroughs. Regretfully, Kubert’s Tarzan, leaner and less muscular than most comic book heroes, was not well-received by the overseas market, being too radical a departure from Manning’s version. His rendering style was very clean, whereas Kubert’s was somewhat sketchy.

|

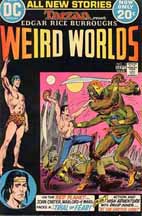

DC had also assumed publication of Korak, Son of Tarzan, which featured Burroughs’ Carson of Venus as a back-up feature. The company also launched Weird Worlds, a showcase for other Burroughs creations. However, sales were poor, and the title eventually merged with Korak to form Tarzan Family. As sales continued to weaken, DC stepped away from the property entirely in 1977.

|

Marvel also published comic book versions of single episodes from the sixth book in the series. Jungle Tales of Tarzan is a collection of short stories that take place during Tarzan’s youth in the jungle, before encountering white men. As such, the individual episodes are perfectly suited for comic adaptation, sometimes by more than one comic creator.

ERB’s heirs had now assumed control over the family empire, and daughter-in-law Marion was upset over one of the short stories published by Marvel. It seems that in 1976, former Tarzan strip artist Burne Hogarth returned to the character for which he is best remembered, adapting the same story. Sharing the same source material, both versions inevitably shared certain similarities, which was cause for concern on the part of ERB, Inc. Even though the same story had also been adapted by Kubert during the DC run, Thomas chose to leave the book. John Buscema would eventually follow.

Tarzan and its sister title, John Carter of Mars, continued to struggle, eventually succumbing to the dominance of the growing popularity of mutants in the Marvel Universe, as well as the diminished profits of licensed properties. Marvel canceled both after just less than 30 issues.

Meanwhile, the newspaper feature continued, though when Manning left the feature resorted to reprints. Eventually, other artists such as Gray Morrow and Gil Kane stepped in for various lengths of time. Mike Grell, who drew the Sunday feature in the early 1980s, says, “Doing the Tarzan Sundays was beyond a doubt the most fun I ever had in comics. I was so excited about my first strip that, as I was putting the final touches on the color guide, I actually started to hyperventilate. Then I started to laugh. A moment like only comes along once in a career.” Today it is still being read by Tarzan fans the world over.

|

To learn about Tarzan's appearances on film, visit www.inthebalcony.com

Praise and adulation? Scorn and ridicule? Email me at philip@comicbookbin.com

Related Articles:

Interview with Edgar Rice Burroughs Estate on John Carter of Mars

Edgar Rice Burroughs Adapted