Watchmen and DC's New Frontier: Faith and Nostalgia

By Zak Edwards

November 2, 2010 - 15:13

$3.99 US

Having just recently read DC: The New Frontier for the first time, I found myself comparing the end of Darwyn Cooke’s take on the history of the DC universe with the conclusion of Watchmen, the book every superhero comic is constantly and consistently compared to. Despite my tiring of this comparison and frequently engaging in it myself, I believe an analysis of these two works side-by-side could be beneficial because of how close their material is to each other. Both, for example, focus on the tensions and paranoia created in America (and the world) during the Cold War, although Cooke’s is written with a certain awareness of more contemporary politics and their similar effects than Watchmen could be allowed. Where I want to focus on today, however, is the endings of each respective texts, how they treat not only the heroes involved, but humanity as well, and the ways in which a faith in humanity may be the lynchpins of both conclusions, but with very different effects.

|

| Ozymandias' famous line shattering the "Evil Scheme Describing" scene. |

In Watchmen, reductively as possible, the enemy is Ozymandias, the former hero who creates a plot which will hopefully bring an end to the tensions created by the Cold War. He is the murderer of the Comedian, one of his few direct actions, and also responsible for the deaths of the population of New York. However, as with most of the characters in Watchmen, and the long discussed major impact of the work, Ozymandias collapses the good-evil binary from the other end. He is ruthless, to be sure, and kills his most loyal servants with poisonous drinks before enacting his plan, yet is performing a terrible deed for the benefit of mankind, and it is Ozymandias’ faith in humanity that is the major point of his plot. The ‘extraterrestrial’ threat of the giant squid which destroys New York is dependent on two primary assumptions of the human populace. First, there is the capacity for mercy and sympathy. The Cold War is brought to an abrupt halt after Ozymandias’ plan, with Russia removing troops and even offering aid to the destroyed city of New York. In the film, the less believable Dr. Manhattan conclusion (Yes, less believable than an extra-dimensional squid randomly exploding into New York) compensates for the increasingly globalized world of the twenty-first century, but is problematic because of the citizenship of Manhattan to the States. Recently abandoned and exiled or not, the plan relies on an intimate knowledge of Dr. Manhattan’s recent political activities and ignores his past as an American soldier. However, the second part of the plan, which is somewhat ironic considering both our current political climate and the beginnings of the Cold War, relies on a population’s ability to be easily manipulated when faced with a nationally (or internationally) traumatic event which changes the collective memory of an entire population. However, just because the entire world is manipulated through a traumatic event does not mean they are incapable of action. The most important detail concerning this is the lack of heroes needed after Ozymandias’ plan is executed, and Rorschach’s journal could be seen to represent the dangers of attempting to move a past ideal into an entirely different present. Much in the same way as Wells’s “The War of the Worlds”, the social changes which occur in Watchmen are the work of normal people reacting to the event, something which The New Frontier is unable to commit to, instead depicting a romanticized view of humanity while still being condescending of their ability to change their own world, as if Cooke has done to all of humanity what James Cameron has done to Indigenous people in “Avatar.”

|

|

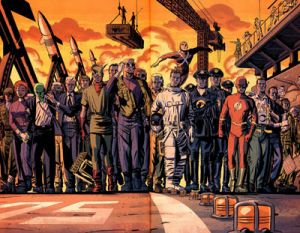

| The united heroes of The New Frontier before they fight against The Centre. |

If New Frontier is to be read as an allegory for contemporary politics, and many would argue against this, than the series suggests we are incapable of change unless someone does it for us, willingly and selflessly. Unlike Watchmen, whose ending implies humanity itself is responsible and capable of changing the world and itself, New Frontier offers up only hopelessness in the form of nostalgia, and the ending is a false sense of security offered to explain how the world as it stands may never be capable of change because of humanities inability to do so without direction and forced involvement of those above us. Watchmen certainly does not leave its audience with a catharsis the way The New Frontier does precisely because of the awareness of the responsibility it implies.

Related Articles:

DC: The New Frontier Trade-Paperback Review

Watchmen and DC's New Frontier: Faith and Nostalgia

Justice League: The New Frontier Special # 1

IDW to Publish First "Star Trek New Frontier" Comic

Justice League: The New Frontier

NEW FRONTIER # 4

DC: The New Frontier #2

NEW FRONTIER # 3

New Frontier # 2