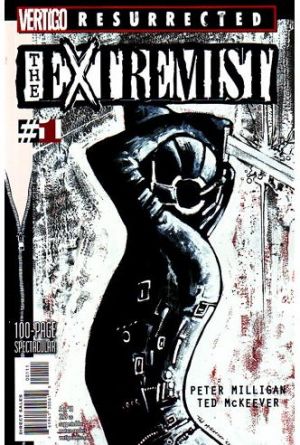

Vertigo Resurrected: The Extremist

By Andy Frisk

December 29, 2010 - 14:58

DC Comics

Writer(s): Peter Milligan

Penciller(s): Ted McKeever

Inker(s): Ted McKeever

Colourist(s): Tom McCraw

Letterer(s): John Costanza

Cover Artist(s): Ted McKeever

$7.99 US

I read The Extremist when it was first published back in 1993. It was one of the early mini series published under the Vertigo imprint. I was in the prime of my first major comic book collecting periods and DC Comics’ Vertigo imprint was my new favorite publisher so I devoured everything that Vertigo printed. Even the series that weren’t big hits, or even very good, at least in my opinion. The Extremist fell into both of the latter categories. I wasn’t a fan of Ted McKeever’s art and I really didn’t know much at all about Peter Milligan, a fantastic author who would go on to helm Hellblazer and write Greek Street among other noted projects such as revamping Shade, The Changing Man and writing Detective Comics. The only other Vertigo title I had read of his at the time was Enigma, which I really didn’t like either.

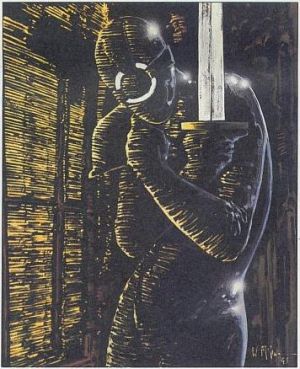

To me The Extremist was a quandary. It was obviously supposed to be an edgy and progressive book so I was drawn to it, but I couldn’t figure it out. It wasn’t a superhero book, but it had a costumed avenger (of sorts) prowling its pages wielding the ever popular katana (no self respecting costumed character of the time period would be caught dead without using or having used a katana at some time in their bloody career as an avenger or a bloody punisher of evil). The story had copious amounts of nudity, sex, violence, and kinky underground sex clubs. It even frankly referenced masturbation in one panel, but the artwork did nothing to make these topics titillating or pornographic in the sense that a Hollywood film with a theme and storyline similar to The Extremist’s, or one of the era’s pin up titles like Dawn, Lady Death, or Razor would in order to sell tickets or issues. McKeever’s art has a unique beauty to it, but it is nowhere near the style of the hyper idealized and anatomically unbelievable look of the typical female heroes of the era. So The Extremist’s female hero, Judy, really didn’t really stoke my late teen years’ libido like say…Psylocke of the X-Men did. There was an anatomically impossible hottie with Asian looks who also packed a psychic knife and psi-blade…what else could have been hotter in the world of comics? The Extremist was a story that seemed to advocate an extreme lifestyle or at least suggest an examination of the transient nature of the strictures of what is considered moral or ethical and how these strictures change of the years, but instead left me with the feeling that such freedom to be or live in the extreme, if you will, really didn’t lead to the gloriously revealed life that Judy’s mentor and bona fide extremist of his own, Patrick (later Pierre) preached that it would. I really didn’t get it, so to speak, so I bagged and boarded the series for posterity and promptly forgot about it. With its republication though, I’ve looked at it again, this time through much more matured and well read eyes.

|

Briefly, The Extremist is the story of Judy, an average all American girl, and her encounter with a secret organization that exists to provide its members with nearly any type of extreme intimate encounter that is morally acceptable, at least according to the most liberal of sexual mores. The character of The Extremist exists to punish (by killing) members of this secret order who commit crimes or betray the order, but as we see, as the story unfolds, The Extremist’s victims aren’t limited to order members. Some are outsiders who find out too much about the order. Most of The Extremist’s victims are members of the order though, and are those who have committed criminal acts such as murder, rape, or other types of sexual abuse. The order is seemingly headed up by the enigmatic Patrick, a man who appears to be immortal in some supernatural way (Milligan often dabbles in the supernatural, even in his most straightforwardly non-supernaturally based tales), and is utterly free in his own sense of the word, sexually and morally. Judy takes up the road tread by her husband, the former Extremist, who was murdered right in front of Judy. Judy is unaware of her husband’s extra curricular (and extra marital) affairs. She follows clues though that lead her to a discovery that not only was her husband morally freer than she (but not enough—this is why he was killed after attempting to leave his post as The Extremist), but that the call of the type of freedom that Patrick offers is much too tempting for Judy to resist, and in the end she just might end up being more of an extremist than her husband.

So as mentioned, Judy travels down the road of extremes while partaking in the most extreme of actions: the taking of human life. Her life becomes consumed by extremes that range from actualizing her deepest sexual fantasy to avenging the murder of two girls. Again though, as I stated, this isn’t a pornographic work, even though some of the themes and images (none of which are graphically explicit) that appear in the work could be considered soft porn. It also isn’t a superhero work, so getting at meaning in this work requires the reader to accept Judy, her and Patrick’s world, and the events of this story as complete metaphor, and to look closer at the characters and attempt to discern what they are representing themselves as well as what the meaning of the word extreme is to Milligan, to the tale itself, and to the reader.

|

As we follow Judy’s journey through The Extremist, we begin to notice a change in her that leads her to, not so much a discovery of her true self, but an honest acknowledgment and comfort with her own drives and desires. While Judy’s husband is dying in her arms, she states that she can only utter the words “I dye my hair Jack…I dye my hair.” Odd yes, but the fact that she never told her husband this fact and he lived (as far as Judy knows) his whole life with her without the knowledge that Judy was not a natural blonde, speaks volumes for the lack of honesty and truthfulness in their relationship. A relationship that neither fully committed too on a most basic level. Perhaps this is why Jack was drawn to Patrick’s world and the role of The Extremist. He longed to engaging in the unmitigated and base honesty that this world offered. The appeal of this world to Judy proves to be even stronger. Patrick helps her open up and get in touch with herself honestly. Patrick brings to life Judy’s most private and honest sexual fantasy (again, not explicitly shown, but explicitly detailed), and as Judy begins to get in contact with innermost desires she becomes more and more extreme…which is to say honest. As Patrick tells her, “For some in the order, sex is the goal, for others, sex is simply one of the means to the goal…”

The goal, as Milligan demonstrates in The Extremist, is much like Patrick’s assertion. Milligan uses sex and a potentially titillating story as “the means to the goal,” and Milligan’s goal is to comment upon the act of being honest with oneself and in one’s life. Such extreme honestly is, by definition, extremism. What is more extreme that taking someone’s life (even if it is deserved in the Biblical sense of “eye for an eye” and all that)? Judy does this repeatedly. Those she kills are criminal in some way, some have committed murders themselves, and at least one is using Judy to commit suicide. Milligan obviously isn’t advocating murder or suicide, but is using the metaphor of the quiet, all-American, bottle blonde girl turned bondage leathered killer and avenger to represent an extreme journey into honesty. What we as readers have to focus on though is whether or not Judy’s type of extreme journey is really necessary. If she would have been honest about her sexual fantasies and desires (and her hair color) with her husband, who honestly had a predilection for such as well, would he have gone down the road that eventually got him killed and turned Judy into a killer herself? It would seem that their fates were not destined and could have turned out differently if they exercised a little honesty, no matter how extreme it might have seemed, in their relationship and marriage.

|

Milligan further demonstrates how being honest with oneself and with ones’ loved ones can avoid tragedy or at least trauma through the character Tony. Tony, the man who stumbles upon The Extremist’s (both Jack and later Judy’s) secret apartment, becomes enthralled in Judy’s story, which he listens to the taped diary of. He becomes obsessed with The Order, Judy’s story, and The Extremist persona. (At this point in the tale it’s unknown whether Judy has remained with the order or forsaken it—it turns out she definitely has remained with it.) Tony is constantly at war within himself as to whether he should put on the suit and attempt to take up where he believes Judy has left off or to return to his wife and young child. As we’ve earlier in Judy’s story though, Judy didn’t hesitate to put on The Extremist outfit. She is “compelled to do it” in her own words. Tony isn’t compelled, and when he finally does try the suit on he realizes how absolutely ridiculous he looks and that he’ll never be The Extremist. At this point he should honestly walk away from the whole thing and go after his wife, who has left him and taken their child with her. He doesn’t though and ends up pursuing Judy and her story to his end. Sometimes being honest about oneself means being honest about what one is not, not just what one secretly or inherently is.

So, with 17 years and a great deal of literary knowledge and reading under my belt, I finally really see what Milligan’s The Extremist is all about. It can be summed up simply as another tale that demonstrates that “the truth shall set you free,” but in reality it’s more complex than that. It’s a comic book that uses an extreme story (pun intended) as a metaphor for the need to acknowledge the truths about ourselves and each other, even the ugly ones. If one never does so, the affects on oneself and those in one’s life can be traumatic. Granted, what happens to Jack, Judy, and Tony is (again pun intended) extreme. It is a metaphoric example of the lengths to which dishonesty, most of all to oneself, can be damaging. Great art though revels in metaphor and tells or reaffirms a truth about the human existence in a new and unexpected way while educating its readers. This is what Milligan’s The Extremist does.

Rating: 10/10

Related Articles:

Vertigo Resurrected: The Extremist

Vertigo Resurrected: Winter’s Edge

Vertigo Resurrected #1