Top Ten Comics of the 1980s

By Hervé St-Louis

March 31, 2021 - 00:36

|

Another major development was the advent of independent publishers outside of the major ones such as DC Comics, Marvel Comics, and a few standouts from previous decades such as Archie Comics. New larger publishers involved in the dominant superhero theme like Comico, First Comics, Eclipse Comics, Capital Comics, Pacific Comics competed with established publishers. Simultaneously, a slew of newer publishers expanded outside of the dominant superhero genre to give a voice to new cartoonists.

Changes in the production of comics forced larger publishers to offer new formats with better paper and colours that competed directly against the best offering of new entrants. At the same time, the English-speaking North American scene finally started to welcome comic from other parts of the world en masse.

Classics as well as critically acclaimed comics from Europe, Japan, and South America began making their way into the specialty comic book stores who now received all of the orders from the newly established comic book distributors that competed against one another to serve the stores and dig up the latest find.

In this crazy mix, independent creators creating black and white comics created a boom and bust from which new publishers such as Darkhorse Comics, Mirage Comics, of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle arose. This decade was one where comics were marketed as not being “just for kids anymore”, tackling topics that would have been censored in the funny pages in prior decades.

Facing extinction from much more popular and thriving Marvel Comics, DC Comics decided to reboot its superhero universe in a year-long maxiseries, one of the first of many in this genre. This, in turn, led to an influx of creative writers from the United Kingdom that generated an effect like the young Brits who had taken the world of music in the 1960s. This new British invasion brought many new names to the world of comics that continue to dominate North American output today.

Comic book conventions, begun in the 1970s became better organized and tried to invite and highlight as many of the older generation of creators that was aging and dying rapidly to meet their fans at dedicated venues. A slew of comic book movies, all cheesier than the previous one was released and highlighted the creative possibilities of the medium. Comics was finally drawing the attention of Hollywood beyond the world of cartoons.

In this article, I attempt to map and rank the most important North American comics of the 1980s starting from an honourable mention down to the first and most influential comic series of that decade. I am not looking at individual issues but whole series, even if I happen to mention the first issue of a series or a run. It was not an easy decision and many arguments can be made by other comic fans better educated than me about comics about which series should be deemed the most important comics of the 1980s. These comics are not just ranked in terms of sales, artistic merit, or literary value. I used qualitative and very subjective ways that are as impenetrable to me as they are to you when determining what are the top ten comics of the 1980s. Enjoy.

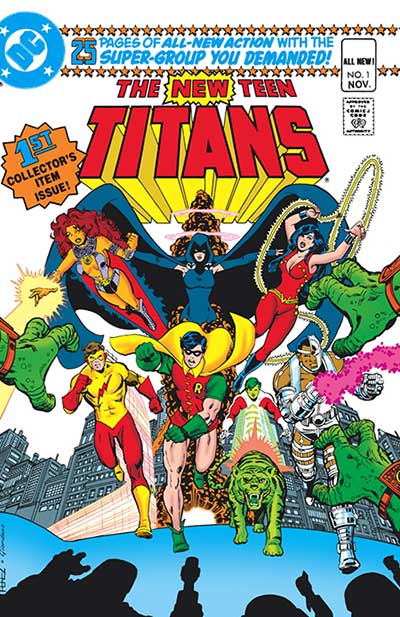

Honourable Mention: New Teen Titans #1 (1980)

But Wolfman and Pérez did more than aged a few sidekicks. They created new teens and added new creations to the mix that would revitalize the publisher, showing an initial interest in diversity and better representation of women in comics. Starfire, Cyborg, and Raven were new characters unattached to older heroes. They had their own trials that soon competed with that of their better-known friends. It is thanks to this series that Nightwing fully outgrew the perennial role of Batman sidekick. Wonder Girl became one of the most rounded girl next door. Starfire added exoticism to the Titans in the form of an alien girl clueless about our world. While New Teen Titans allowed DC Comics to resist a full onslaught by Marvel Comics, was it still does not merit, to me more than this honourable mention.

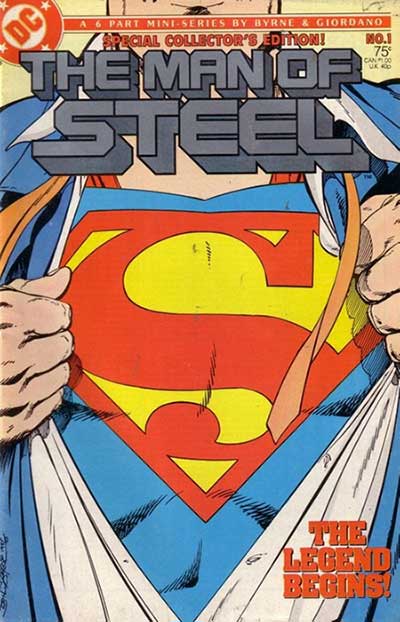

10-The Man of Steel (1986)

|

Byrne had wanted to tackle Superman since the failed deal surrounding between Marvel and DC Comics where the former would publish the latter’s comics. Byrne loved a challenge and when he was given an opportunity to revamp and rethink Superman, he did so. His revamp had been the first and the most provocative ever. He brought back Superman’s parents, got rid of much lore and secondary characters that had crippled development of the hero for decade. He made Lex Luthor an evil tycoon instead of just a mad scientist.

Suddenly, Superman was fresh and interesting again. He was no longer overpowered and capable of doing everything. He was more hesitant, less infallible, and much more a man. Clark Kent was no longer a cover for Superman but his real identity, who he really was. As the historical flagship character of DC Comics and symbolically the first superhero (The Phantom was first but in comic strips, not comics), a revitalization of Superman was important to comics in the 1980s as they were dominated by superheroes. This one goes to Superman.

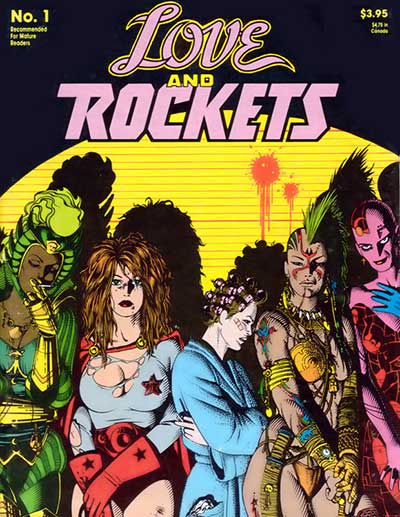

9-Love and Rockets (1981)

|

Love and Rockets had titular superheroes but they were not the central characters. Stories focused mostly on the relationships between a wide cast of characters whose stories and interaction have now span decades. They aged. Such a series would be unique today but back then, it was ground-breaking and something not told from the usual perspective of white Anglo-Saxon or Jewish men.

What differentiated the comic from everything else was the intricate collaboration of the brothers. Unlike many comic book creative teams, they did not work on the same comic, adding more than sum of their parts to a new work. Instead, they each did their thing but published together allowing both brothers to shine. Even though each has published independently of the other, the Love and Rockets format is a unique collaboration in American comics.

The other aspect of Love and Rockets that was ground-breaking in 1981 was the cartooning of the brothers. While each has a different style, Jaime’s work being rounder and softer, than the edgier Gilbert, together they created the Love and Rocket look. It is inspired by Archie Comics and Dan Decarlo but also like European ligne Claire. The brothers are also not afraid of producing cartoons. The break the reality trap that 1980s would further plunge into in favour of lighter illustrations that hide much depth and angst.

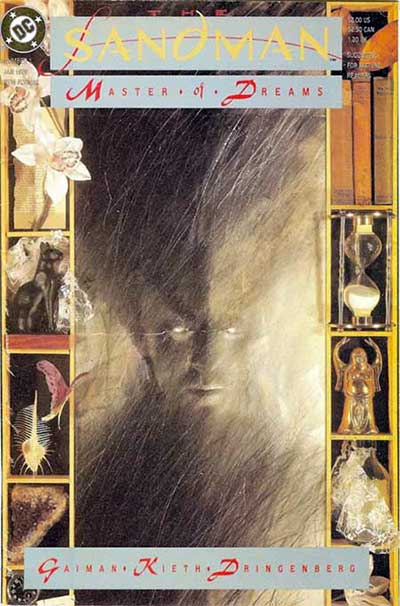

8-The Sandman #1 (1989)

|

Gaiman, notwithstanding what his fans will argue, played with superhero tropes without making it seemed that he was writing superhero comics that women and older male readers would not be ashamed of reading. Thus, they could proudly claim that comics were not just for kids while reading stories that were superheroes for snubs and young adults. Of course, DC Comics and Gaiman would never say so out loud, fearing that that would destroy the illusion that the comics were something new and different. The whole marketing around Sandman was that it was not a superhero comic and something that could appeal to older readers unfamiliar with the genre.

As harsh as this criticism may seem, Sandman was not a very intricate comic with the most complex situations. It was a comic that could hit readers’ sense just enough to make them seem smart and different from people reading Archie, Spider-Man and Batman. The thing is that it worked. Sandman also began the age of the fable comic book writers having ascendancy over artists in comics. This was interrupted by the Image Comics gang in the 1990s, but following their implosion later that decade, the writers became the most important collaborators to most comic projects. Sam Kieth, the original illustrator of the series is a great cartoonist but not known mainly for having contributed to Sandman. It was Gaiman’s baby. Had it appeared earlier in the decade, perhaps Sandman would have been higher up on my list.

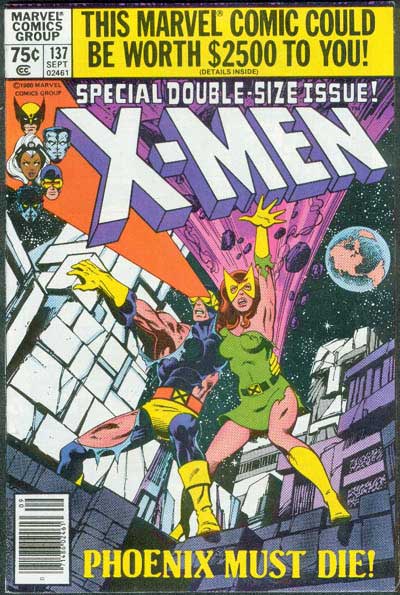

7-Uncanny X-Men #129-138 (1980)

|

The best was that everything that led readers to this story while Byrne and Claremont collaborated, and everything that followed, while the pair was still on speaking terms was part of the myth-building that propelled the X-Men for decades. It was the best superhero material in the world of comics at the time.

The Dark Phoenix achieved many greats here. They completely pushed aside the Fantastic Four and the Avengers at Marvel as the premiere superhero team of that publisher. But they did more. They also pushed the standard for what a superhero team, DC’s Justice League aside. It took Marvel over 20 years to recover from the domination of the X-Men, only achieving this thanks to cinematic representation of the Avengers. As for DC Comics, it forced the publisher to seek to reinvent its flagship team comics many times, going as far as aping the X-Men in the form of the Detroit Justice League.

That ability to force your competitors to reinvent themselves, whether they are part of your own family or from the company next door is quite a feat. While the cosmic scale of superhero comics was not new, it was brilliantly expanded with the Dark Phoenix saga.

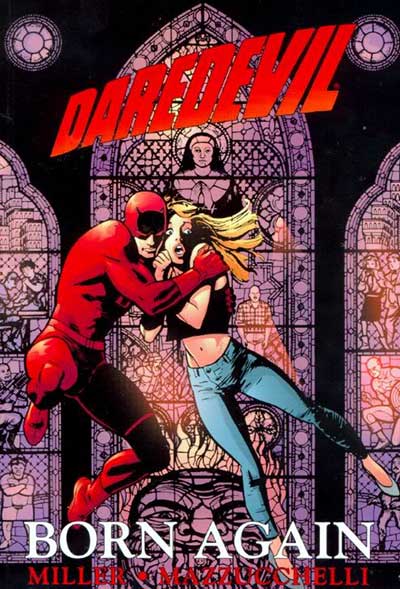

6-Daredevil #227-233 (1986)

|

Stories where a character is broken are not new in comics. But Miller’s take was the best at the time. Miller returned to familiar grounds with the Born Again story, adding a catholic spin to Matt Murdock’s back story. When creators return to older material, they often try to outdo themselves and it may not always turn well. But here Miller showed restraint and let Mazzuchelli tell his story the way he never could. But Miller was a smart writer, always writing to the strength of his artists.

Daredevil wasn’t a character that drew sales numbers like Spider-Man, who he was originally thought of as a poor imitation. Instead, he was the character that people wanted to write and draw because of the prestige it would give them. Born Again was not really a superhero comic. It was more street level and closer to courtroom drama with a few ninjas thrown in the mix.

Interestingly, when Frank Miller’s best work on Daredevil is adapted to film and television, Born Again, thematically is never the first story told. It cannot work this way. It is more the coup de grace that ends the journey of the character. I argue that Miller’s work on Born Again was so important, that in a way, he broke the character, and nothing ever again can match its brilliance. The only stories I’ve read that come close to Born Again are those written 15 years later by Brian Michael Bendis and drawn by Alex Maleev.

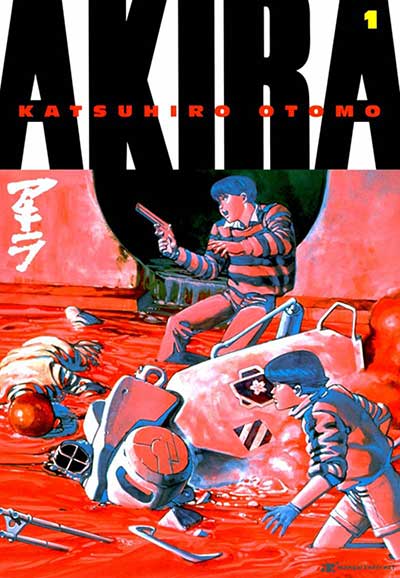

5-Akira (1982)

|

Akira, the tale of post nuclear Japan dealing with the complexities of its society and competing interests was the perfect tale for those comic readers that had already discovered materials from Japan. The energy cartoonist Katsuhiro Ōtomo put in the comic was like what creators like Frank Miller were trying to accomplish here. Except, Ōtomo was more in the same leagues as Mœbius than most North American creators. His work showed the discipline of Japanese cartoonists, creating pages of contents regularly for avid domestic readers.

Akira’s designs were not always easy on the eyes. The characters’ faces were ugly, but it was done on purpose. The lines of backgrounds and the design of everyday objects and technology was beyond anything drawn in North America at the time, except for Geoff Darrow. What made Akira special was that it was distributed as interstitials, a staple of manga, but much newer in North America.

The story was available through many publishers over the years but was in 1988, Marvel’s response to DC Comics. Marvel’s imprint Epic tried to capture some of the energy of independent comics and some of the ground-breaking work being released by DC Comics, always in the attempt to capture a more mature audience that was ready to transition out of comics. To that effect Epic published works by comics’ greats, such as Mœbius, and Frank Miller.

The magic of Akira was the computer colouring done by Patrick Oliff. In hindsight, he was using a lot of gradients to colour Akira and to give it a dark edge. It worked and instantly, Akira would capture the imagination of readers into its web of urban science fiction and nihilism. Akira is ranked higher here, because unlike similar works by Mœbius also published at Epic, it generated a substantial audience eager for more Japanese comics and ready to try more. This was not something that Mœbius’ visit in North American comics, achieved for European comics.

4-The Dark Knight Returns (1986)

|

Grim and gritty could be nothing but a genre in film akin to film noir. But Miller’s influence reshaped comics for decades forcing every superhero creator to darken their characters, to make them a bit ambiguous and less cavalier and honourable. Their flaws, unlike Marvel characters of the 1960s were not impediments to surpass but characteristics that made them less likeable.

In comics, a good idea is never left alone or unused. Thus, before the decade ended, The Dark Knight Returns was the template for the superhero comic mixing a disdain of then President Ronald Reagan in a story that was nothing more than an orgy of poorly thought political ideas.

Miller often has narrative flaws in his work and The Dark Knight Return is full of them. But the excess that would have made the work of another creator ludicrous became the signature the model used by many other creators at the time, and even today. Batman was never as depressing as in The Dark Knight Returns but it sold like hot cakes for DC Comics.

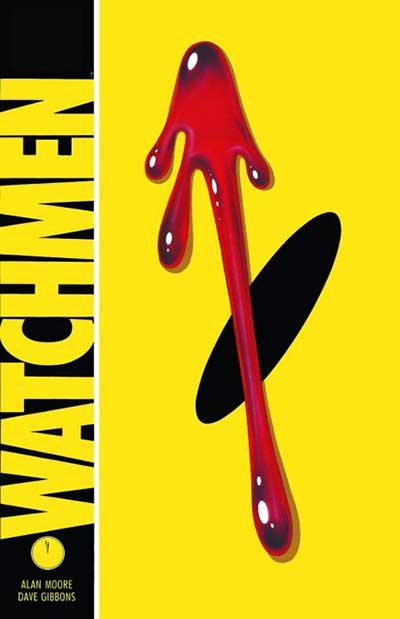

3-The Watchmen (1986)

|

Everything Moore, did, he did with a finer touch than Miller could. And to this day, the fodder created in The Watchmen can serve as an allegory for other social ills, such as racism, and homophobia. Miller could only scream at issues in The Dark Knight Returns but he could not expose a situation to the same extent as Moore and Gibbons did.

What worked in their favour is that they used the comic genre, the medium to tell a story that was not ashamed of being a comic book. The Watchmen was not a pretentious graphic novel or a comic only geared for mature readers. It was a comic that used classic superhero comics as an inspiration and then broke down the formula in front of readers.

Since, many comics have been about the deconstruction of a genre. Moore has always specialized in that, but he did it very well with Watchmen. He played with the nine panel grid, he played with cliff-hangers and the fact that the series was published in twelve instalments to create more anticipation and interest in the tale. So was The Watchmen the best superhero comic of the 1980s, I still maintain that the X-Men was, as Moore was interested in understanding the formula, while Claremont and Byrne perfected it.

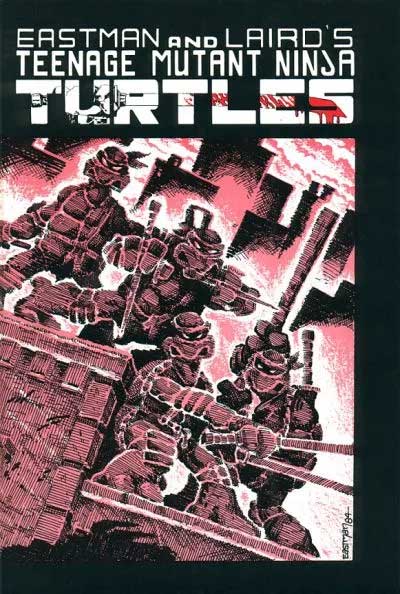

2-Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles #1 (1984)

|

Peter Laird and Kevin Eastman sold the “Turtles” when they wanted to. They had complete creative control over their comic a decade ahead of the Image Comics founders. The derivative product of their comics were the most popular properties in the second half of the 1980s while coming from humble beginnings as a black and white comic.

The success of TMNT helped create a bubble that would soon bust after the craze around black and white comics that helped the establishment of distinct comic book retail market would collapse. However, while all their competitors were collapsing, the Turtles remained popular and continued to thrive. That’s quire a legacy for a comic series that did not come from Marvel nor DC Comics. The human part of comics, which are the creators matter very much and often looking at comics, we tend to forget that they are part of any successful formula. Therefore, I rank the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles ahead of so many comics in the second spot of this top ten list.

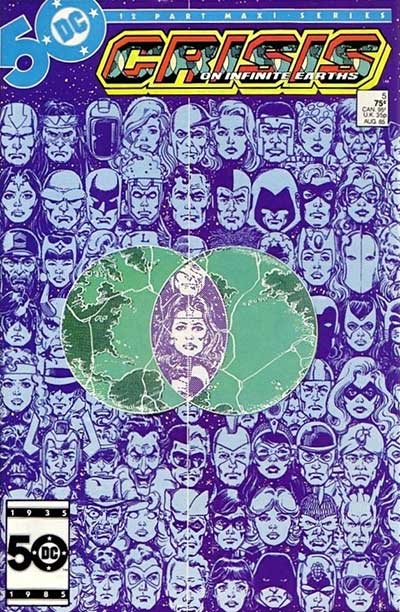

1-Crisis on the Infinite Earths (1985)

However, there was a brief time in the early 1980s where comics could have ridden itself of superheroes, but that plan ran afoul the moment Crisis on the Infinite Earths showed up. DC Comics was dying with very series selling well. DC Comics had always been committed to preserving its rich history but was compelled to do so at incredible length. Everything had to make sense. This is not an approach that was favoured by Marvel. But DC Comics was obsessed with its continuity and explaining everything, much like Geoff Johns.

|

It worked so well, that Crisis beat Secret Wars, the competing the maxiseries from Marvel Comics. And the story still reverberates today. One entity called the Anti-Monitor wanted to consume several parallel universes or something like that. Heroes from many dimensions and time rallied together to defeat the new evil. In the end, many characters that had been popular in the previous Silver Age of comics from the late 1950s to the late 1960s ceased to exist. DC Comics cleaned house removing much of the dreck that would slowly crawl back over time.

DC Comics cut off several of its limbs in order to better grow in the future. The new DC Comics still did not best Marvel, but it was ready for a new decade and would soon be free to innovate in comics. However, I argue that this exercise left the company and its readers a bit schizophrenic. Can you imagine the mental effort of reading a Superman or a Batman comic only to have to recall that Wonder Girl here does not have her memories of being Wonder Woman’s sidekick because they are the same age now… I thought the point of the Crisis was to streamline and make things simple, not to remember obscure trivia like who Fel Andar, is.

But that is DC Comics for you and that is the rich legacy of Crisis since. It made us car even more about the Wildcat of Earth One. Crisis asked readers to invest a lot of mental effort which DC Comics would gladly erase and restart every few years, just for fun. It celebrated the weird world of superhero comics by taking it all seriously. For many of this initial investment in the fictional world of a comic universe is still paying off. For some of us, the knowledge of Crisis is useless, but the visuals as drawn by Pérez can still stir the imagination. Crisis on the Infinite Earths, taken as one unit remains to this day the most important comic of the 1980s.

Check out

Related Articles:

Top Ten Comics of the 1980s

The Top Ten Trending Articles at ComicBookBin for August 2015

The Top Ten Trending Articles at ComicBookBin for July 2015

Top Ten Female Action Figures

War Fix In Top Ten

New Top Gun Game Nintendo DS