Mystique: Crossing the Boundaries of Sex, Gender and Human Nature

By J. Skyler

August 23, 2012 - 12:08

|

Before we can understand her representation of trans-related issues, it is important to first separate sex from gender. Among sociologists, psychologists and medical professionals, the word sex is used to describe a person’s chromosomal make-up (XX for females, XY for males) and reproductive organs. Gender, however, implies psychology—the mannerisms, characteristics and behaviors which shape a person’s sense of manhood or womanhood—and the degree to which such attributes are dependent on biological factors or cultural influence. Secondly, we must separate sexual orientation from gender identity. Whether we are discussing heterosexuality, bisexuality or homosexuality, what defines sexual orientation is what sex a person is attracted to. Gender identity, however, reflects one’s inner sense of being male or female, regardless of their physical anatomy. When we discuss gender identity, sexual orientation is more or less irrelevant. Generally speaking, men—regardless of sexual orientation—typically develop a male gender identity, while women—again, regardless of sexual orientation—usually adopt a female gender identity. Even among gay, bisexual, or straight men who are comfortable expressing feminine characteristics, or lesbian, bisexual and straight women who possess masculine attributes, there is still a fundamental difference in exhibiting certain qualities and seeing one’s self as literally being the opposite sex.

In classroom forums, or other public speaking venues where I am a panelist discussing LGBT culture politics and history, I usually introduce myself by stating that my name is Skyler and “I am transgender.” During the course of these panels, I typically get fielded the most questions in comparison to the other participants. Since people look at me and see a presumably “ordinary” male (aside from the fact that I love cosmetics), questions such as “what does that mean?”, “are you male or female?”, “have you had sex reassignment surgery?” are among the most frequently asked. My answer is usually as follows: “I am biologically male, meaning my chromosomal make-up is XY just as any other male, but my gender identity or psychological sense of self is female. I’ve been aware of my gender identity since my earliest memory at age 4. That being said, I have not had sex reassignment surgery and I have not undergone hormone replacement therapy.” Since SRS is the recommendation for gender dysphoric individuals (transsexual being a medical term specifically referring to those in the pre-operative, in-transition, or post-operative stage) the most common follow-up question is “are you planning to transition in the future?” The simple answer is no for a multitude of reason, but primarily because of the fact that surgery (of any kind) terrifies me to no end. I’ve often joked that the only way anyone would be able to get me into the ER after an accident is if I were instantly knocked unconscious, but that’s more a matter of fact than an exaggeration (it’s ok to laugh about it, I do quite frequently).

In the book Biology of Human Reproduction (2002), author Ramón Piñón states that “[f]or nontranssexuals, the discordance between gender identity and anatomy is impossible to conceive… The transsexual does not deny her or her anatomy; rather the anatomy is the source of psychic pain. The discordance has varying degrees of intensity, ranging from mild dissatisfaction and vague sense of unease (a sense of being trapped in the wrong body) to a pronounced dislike, even loathing, for one’s body, particularly its sexual characteristics.” Personally, I loathe having a penis, as well as other male characteristics (for the anatomical females reading this, picture for a moment what it would be like for you to wake up with a full beard and having to shave your face), but the idea of reconstructive surgery—for me—is unappealing; I don’t believe I would be able to walk away from it without a sense of dissatisfaction, despite my discordance. However, most individuals who opt for SRS are perfectly happy with genital reconstruction, and in fact, lead much psychologically healthier lives after their transition. The choice to transition or not will vary from person to person—therefore, my own personal experience should not be taken as being uniform for all gender-variant people.

|

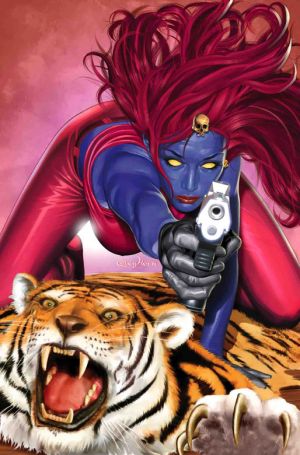

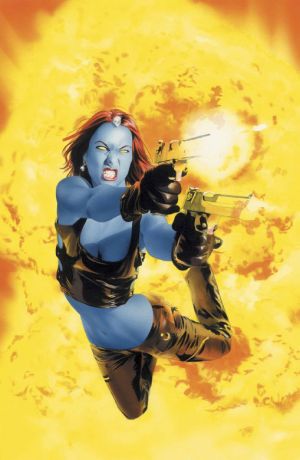

Being a girl, and yet a boy, my affinity for Mystique led me to view her not only as an analogy for trans-identification, but for a more universal theme of gender non-conformity. Mystique was born female and possesses a female gender identity, but neither defines her. She is as comfortable adopting a masculine persona and living as a man as she is in her natural form—an atypical mindset in a world where sex and gender so rigidly define all cultures and our perception of one another. Most people believe that as human beings, we are divided into being exclusively masculine or feminine. In the article “The Measurement of Psychological Androgyny” by Sandra L. Bem in the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology (1974), the author writes that “[i]n general, masculinity has been associated with an instrumental orientation, a cognitive focus on ‘getting the job done’; and femininity has been associated with an expressive orientation, an affective concern for the welfare of others.” The reality is that while men may more frequently exhibit masculine traits (aggression, ambition, autocracy) and women may more typically express feminine characteristics (passivity, empathy, compassion) both sexes naturally possess each of these qualities to varying degrees. Thus, androgyny is an innate aspect of human psychology, regardless of sex, sexual orientation or gender identity. It isn’t feasible for a man to be in a constant state of aggression any more than a woman can be in a constant state of passivity. Rather, both men and women can “be both masculine and feminine, both assertive and yielding, both instrumental and expressive—depending on the situational appropriateness of these various behaviors[.]” Part of what makes Mystique such an effective character is her sense of fluidity, her mental capability to adapt to any situation as it arises. As the authors of Handbook of Gender Research in Psychology, Volume 1 (2010) wrote, “[p]sychological androgyny can be understood as both stereotypically feminine and masculine characteristics. Androgynous individuals do not conform to expectations based on gender alone.” Mystique has no concern over what is deemed “appropriate” for a man or a woman, but she will utilize gender preference or stereotyping to manipulate those around her, taking advantage of any situation.

|

Mystique’s villainy also illustrates a negative stereotype about transgender individuals: the idea that we are inherently deceptive and gain self-gratification out of "misdirecting" others. However, given the long history of transphobic violent crimes, including assault, rape and murder, concealing one’s birth sex as a matter of private medical history can be a matter of life or death depending on the situation. In Violence, Victims, Justifications: Philosophical Approaches (2006), author Felix Ó Murchadha states that “a GenderPAC study in 1997 found that almost 60% of the participants had either been victims of trans-based violence or harassment, and 47% of the participants reported having been assaulted in some way over the course of their lives.” In a similar vein, Mystique has been depicted as leading multiple lives, hiding her status as mutant and in some cases, as a born-female. She has abandoned and adopted a number of identities after being “outed” in order to escape persecution. Had her environment been nurturing for those of a mutant background, and especially for shape-shifters, misdirection and concealment—and most importantly, criminal activity—would have been entirely unnecessary. Though Mystique cannot be absolved of all her sins, she does represent a tendency to blame the victim, even when the abused rise up against their abusers in a violent and militant fashion.

While her classification as a transgender character is understated, what has gained more universal acknowledgement is Mystique’s bisexuality. Since the now-defunct Comics Code Authority forbade any depiction of same-sex relationships, her sexual orientation could only be hinted at for a number of years. The Supervillain Book: The Evil Side of Comics and Hollywood (2006) notes that “[h]er relationship with the blind precognitive mutant Destiny goes back at least to the 1930s. Though [writer Chris] Claremont did not make it explicit, he implied that Mystique and Destiny were lovers. In fact, in the 1930s Mystique adopted a male identity, ‘Mr. Raven,’ as Destiny’s companion.” Her sexual orientation also makes her an unprecedented bisexual icon, as bisexual people have also face persecution from gays and lesbians as frequently (and ironically) as transgender individuals. Bisexuals are often seen as being as equally “deceptive” as transgender people due to the fact that they are assumed to be incapable of monogamy. Moreover, the invisibility of her bisexuality epitomizes the concept of bisexual erasure—the assumption that bisexuality does not exist or the tendency to ignore the bisexuality identity of those known to have been in opposite and same-sex relationships by heterosexuals, as well as gays and lesbians alike.

|

In honor of my 28th birthday, take a moment to listen to Lady Gaga’s “Hair” from Born This Way, available on VEVO!

Follow me on Twitter @jskylerinc

Related Articles:

Harry Octane: Virage mystique

Mystique: Crossing the Boundaries of Sex, Gender and Human Nature

Mystique

Mystique

Mystique # 6

Mystique # 5

Mystique # 4