Comics/Culture #4: Watchmen's Squid

By Zak Edwards

September 19, 2014 - 22:14

True to form, the final episode of The Wire, “-30-“, is really depressing. The title references a journalistic note that typically appears at the end of a story, but of course that’s a bit of a misnomer. Nothing really ends in The Wire, after all, and nothing truly changes. It’s sort of the point. Characters that have died, been promoted, or moved on are replaced by a younger generation so the entire series becomes cyclical. In the case of Carver, he becomes the new Daniels, and every major character’s next chapter, as it were, is simply is reiteration of someone else’s past. It can’t end, to end would betray The Wire’s chosen genre.

|

The Wire’s strange adherence to realism, to it’s vision of the “real” Baltimore, is exactly why the ending leaves its audience out to dry and why it makes such compelling television. The agendas, competing aspirations, and bureaucratic mechanisms paralyze everyone, or rather recycles them in a cycle of destruction and revival. There can be happy endings, but they must be tempered, any emotion elicited has to be given the larger context of the series’ other characters and system, systems including it’s real Baltimore itself. In short, The Wire’s claims to realism force it to end up back where it started. It’s a caveat of its chosen genre and Watchmen comes very close to a similar realization until an animal, a wholly unrealistic animal, is forced through the narrative. With that intrusion, Alan Moore’s trademark cynicism can to give way to the possibilities of escaping its crushing reality, its need for that happy ending and classic superhero finale, and Moore’s own utopian aspirations.

Watchmen was obviously one of the landmark comics of the Dark Age, a movement in mainstream comics that (mis)took cynicism and grit for realism and, in doing so, reexamined the superhero. Caped crusaders became sociopaths, sufferers of extreme trauma, maladjusted, and through that lens we discovered that the “hero” in superhero is a misnomer as well, a potentially dangerous mislabelling that works on a structural level.

Curiously, The Wire’s cycles of violence are a mainstay in the superhero genre, which is evident in most major superhero comics and even groundbreaking runs in different stories. Every change must be tempered by the status quo, the potential for another story. For all the changes Grant Morrison brought to Batman in his recent run at the character, for example, the world is pretty much left as it started. Batman gains and loses a son. His international conglomerate Batman Inc. is started and dismantled. The entire story shakes up the status quo only to return to normal. All the violence, the deaths, and everything else, are ultimately fruitless and serve no larger purpose than immediate necessity.

But within these cycles, superhero fiction is allowed to speculate, to imagine possibilities. Entire worlds can be created to see what would happen. A status quo may be a returning point, but the deviation can be all-encompassing and those possibilities continually inform the baseline status quo. The Age of Apocalypse, for example, imagined a world where Apocalypse won and Rick Remender spent much of his Uncanny X-Force run looking at how that universe informs the standard Marvel universe. Brian Michael Bendis’ run on the ironically titled All-New X-Men literally injects the original status quo into a world with a need for continuity. For the old guard, as it were, to come and evaluate where everything has gone. The Wire’s entire narrative wraps into a perfect circle, but a superhero comic acts more like a rock in water, spinning out multiple circles that meld and fall away, all dependent on an original idea (or rock).

|

| Watchmen being real, complete with bullet deflection. |

This is where Watchmen, allowed to exist within its own tiny universe without an inherent demand for ongoing stories, differed. It was allowed to end this creates a tension between realism’s ultimate and essential failures with the superhero genre’s desire for change and speculation. When we talk about art as a mirror or a hammer, realism generally falls into the category of mirror. Many other genres can cross into the hammer. Watchmen shows that realism’s hold can be invisible and strong, so a jarring intervention of fiction is necessary for Moore’s ending.

For all its cynicism and grit, Watchmen ends with Moore’s own dissatisfaction with the world itself, and a very traditional form of utopianism. And we don’t need to go back too far into the history of science fiction to see where Moore’s squid comes from. It’s lifted from The War of the Worlds, a work that Moore has used more than once.

The War of the Worlds ends with a sort of global socialist utopia with countries sending aid to Britain and banding together against the extraterrestrial threat. With something outside to fight against, the post-invasion world in Wells’ novel becomes this sort of socialist paradise, or at least the beginnings of such a vision. The ending is a fictional representation of discussions Wells probably had at the Fabian Society, a Victorian group that discussed socialist means to change the world, and obviously something Moore himself believes in himself.

|

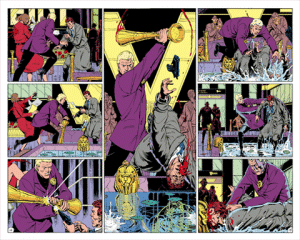

So when Moore’s own graphic novel, steeped in his particular brand of realism, comes to its end, realism’s cynicism competes directly with Moore’s utopianism, the superhero genre’s desire to speculate something other than reality. The result is jarring and almost confusing, a squid blowing up in New York, a means through which Moore’s world can copy Wells’ and move towards a definitive utopia.

Essentially, the squid is a perfect manifestation of something alien to Watchmen thus far. It may show up a few times before it appears properly at the book’s climax (which is, fittingly, violent and plot-based like most superhero story arcs). The squid doesn’t quite make sense to the overall narrative. Dr. Manhattan is long purported as the only individual with superpowers, but the squid is the result of experimenting on people that have ESP. The world itself, for all of Moore’s claims to realism, actually holds latent supernatural elements, people born with ESP, that counter Dr. Manhattan’s freak accident origins as the birth of the superhuman.

That squid is a forceful, near illogical invasion on the narrative itself, more than just the plot, but the foundational structures on which Watchmen is supposedly built, what made it famous and important.

Because it turns out that Watchmen isn’t realism and never was, it’s pure fantasy and conjecture from the beginning, never once adhering to a strict for of realism that’s present in something like The Wire, where the reality of situations is more important than the dreams of the author. Only through the forceful injection of something seemingly otherwordly can we see the utopian vision Moore desires, and the backwards changes he makes in order for such a vision to be realized.

And that’s why the squid matters.

Related Articles:

Comics/Culture #5: Superheroes vs. #HeForShe

Comics/Culture #4: Watchmen's Squid

Comics/Culture #3: Stray Bullets and Billy Joel

Comics/Culture #2: The Economics of Spoiler Alerts

Comics/Culture #1: Marvel's Failed Diversity