The Collected Doug Wright Vol. 1

By Hervé St-Louis

May 13, 2009 - 22:09

Drawn and Quarterly

Writer(s): Doug Wright

Penciller(s): Doug Wright

Inker(s): Doug Wright

Cover Artist(s): Doug Wright

ISBN: 978-1897299524

$39.99 US

Montreal publisher Drawn & Quarterly released the first volume of The Collected Doug Wright, billing the artist’s as “Canada’s master cartoonist” comparing him with Charles Schulz, the creator of the comic strip Peanuts. Reporter Brad Mackay worked on the compilation and the archival research needed to assemble the book. The first volume collecting the body of work Wright did in comic strips and print advertising from 1949 to 1962.

Doug Wright was born in the United Kingdom in 1917 and immigrated to Canada in 1938 to work as an illustrator for the Sun Life insurance company, then, headquartered in Montreal, Quebec. Wright’s claim to fame is based on Nipper a family-oriented comic strip that was first published in the weekly newspaper, The Montreal Standard.

|

Publisher Chris Oliveros and writer Brad Mackay are making bold claims about Doug Wright being Canada’s master cartoonist and the Canadian equivalent of Charles Schulz, which unfortunately do not stand up to closer scrutiny. What Wright had going for him was a sure pen, and fluid storytelling skills allowing him to eschew written captions in his comic strips. But in terms of spirit, Wright’s work is nowhere near Charles Schulz or other celebrated cartoonists like Walt Kelly. As for being Canada’s master cartoonist, this is another brave claim that is more akin to chest beating than reality. At best, Wright was a good cartoonist, but not the foundation of comic strips as an art form in Canada. His work speaks for itself.

Oliveros and Mackay, both English Canadians seem to forget that any claim to be a master Canadian anything means that the person to whom the title is assigned to must be a stellar performer that is critically acclaimed in both of Canada’s solitudes. Publisher Chris Oliveros, though he lives in Montreal, should know better about the reality of Canada’s culture. However, his and Mackay’s claims are only symptomatic of the natural tendency of English Canadian elites to think of English Canada as the “real” Canada, while anything French or from First Nations is tolerated as exotic additions that spice up the Canadian makeup. On that score alone, Oliveros and Mackay’s claim that Doug Wright’s work somehow transcends Canada by being the ultimate the country can offer is a ludicrous claim at best, and publicity jingoism at worse.

Wright lived during the most important years that would define Canada as a nation and Quebec, as a province which was the center of Francophone society in the Americas. Looking at the strips contained in this volume, it is almost impossible to feel any influence of the Great Darkness and the Quiet Revolution that were affecting Montreal and Quebec, while Wright was churning a pile of comic strips every day.

What one can feel about Wright’s work is that he upheld a strict Anglo-Saxon White Protestant culture which was existent in the Montreal he lived in, but was continually encroaching and confronting the emerging nationalism of the French majority which was treated as an underclass not worth treating with dignity.

As Gabrielle Roy’s novel about the period, Bonheur d’occasion (The Tin Flute) shows, Montreal was a segregated city where the rich and dominating English upper class blocked the economic prospect of the French-speaking majority. Like Germinal a century before, Bonheur d’occasion forced the French-speaking majority to look at the sad state of its fabric where basic health care services, higher education outside the liberal arts and economic mastership of its fate was controlled by a minority for which Doug Wright drew self congratulatory comic strips daily. Montreal in the 1950s and 1960s was an Anglophone city. All services were offered in English only. Store clerks and restaurant waiters attended clients in English only, even if the majority of the people who lived in the city were French-speaking.

The almost complete absence of any flavour of the multilingual state of Montreal is more a conceited attempt by Wright to ignore the reality of the city whose night life he so much enjoyed. To this day, Anglophones from across Canada think of Montreal as nothing but a cheap Paris, with bars and booze every second street. Montreal was the original Sin City, and from Mackay’s introduction, it seemed that Wright loved that part of the cosmopolitan city, while furiously ignoring the underclass that made it work.

If Wright’s work deserved to be labelled as the best Canada has to offer, it needs the same breath of ideas and humanism of the work of some its contemporaries. The work of Mordecai Richler, a contemporary of Wright is a good example of what Wright lacks in grandeur. Richler was born from a Jewish family in Montreal. A writer, his work, although based on Jewish characters, exudes the flavour of the city he lived in. Richler’s The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz could not be mistaken for occurring in any other city but Montreal. Looking at Wright’s beautiful pantomimes, this reviewer could not tell whether the stories occurred in Mount-Royal, the small English enclave in the middle of Montreal, or in the Mount-Royal neighbourhood of Alberta-based Calgary. When a master’s work is bland, lacks humanism and could have occurred anywhere, should it be considered the best a country has to offer? If so, Canadians really are boring.

Wright also drew for the rest of Canada. His work was not just meant for the local Montreal English establishment. English Canadians across the country were also treated to Wright’s Nipper and other advertising cartoon. Nipper, the story of a toddler constantly involved in mischief was also translated for the Francophone market where it was called Fiston (Son). But some of Wright’s onomatopoeia had to be translated for the French audience and according to Mackay, Wright was less supportive of that and grew continually angry at the evolving social revolution of the 1960s that witnessed French Canadians, assert themselves as Québécois and masters of their own fate in their own land.

To compare Wright to Schulz, the former would have had to maintain a propos, a body of work that challenged its readers. Schulz, a contemporary, did not ignore the changes happening in American society, like Wright ignored what was happening just outside the window of his downtown office. Schulz introduced a black character in his comic strip at a time when blacks were still controversial figures only good for comic relief. Schulz had strong female characters and his philosophical musings did show concerns for other realities than the status quo. Although not a leading figure of change, Schulz was far from being a reactionary standout like Wright. Schulz was a master wordsmith that with but a few words could create a complex and profound short story, while Wright relied on his aesthetic skills only.

Wright’s office was located in the Sun Life Building, a symbol of Montreal’s economic might as Canada’s metropolis. At the time of its construction in 1931, it was the largest building in all of the British Empire. Its construction was a direct challenge to Cathedral Marie-Reine du monde, a replica of Saint Peter’s Basilica of Rome. The cathedral had been built by the French Canadian Catholic Church in what was seen as prime WASP real estate decades earlier to exhibit the power of the French population of Montreal. Well-read natives of Montreal and good historians would not ignore the symbolic importance of such things in their research. None of that insight is available in Mackay’s introduction. As an Ontarian, he does not understand what it meant to work in the Sun Life Building for a man like Doug Wright. He does not understand the ascendancy Wright automatically had over 90% of the population of Montreal and how he was elevated as an elite and mouthpiece for the English-speaking establishment. His publisher, Oliveros although a Montrealer, seems to have lacked the proper knowledge to guide Mackay's research.

Wright, like 700,000 thousands of English-speaking Montrealers, eventually left Montreal and transplanted themselves to Ontario where their numbers and economic might was sufficient to tip the balance in favour of the Great Lakes upstart and its Queen city. Toronto became the new metropolis of Canada, while Montreal was punished for affirming the reality of its nature as a city inhabited by a French Canadian majority. Sun Life and the majority of the financial industry that was headquartered in Montreal moved to Toronto. Wright chose no other day to move his family and himself out of the province of Quebec but Saint John Baptist Day, the religious and national holiday of all French Canadians and the patron saint of French-speaking Canada.

|

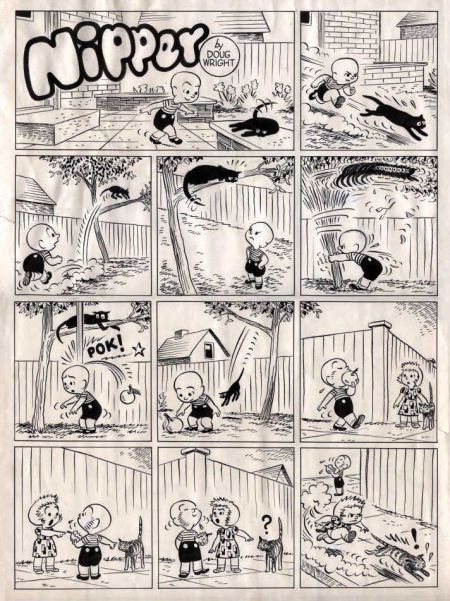

| Uncleaned scans of Nipper |

The editors used many archives that were not cleaned up properly before being printed. For the price of this book, you would think the publisher would provide cleaned up artwork without newspaper ridges. That’s a sign of poor editing. God made Adobe Photoshop so dirty newspapers comic strips scans could be cleaned up.

What is most interesting about Doug Wright’s work is its visual aesthetics. Given his lack of ideas and context, his penmanship is impressive. Wright uses curt lines that he fails to close in many of his drawings, suggesting more than a form, but not a totally rounded figure. This approach is quite useful at displaying the quick gestures and movements that populated his work. His lines are sometimes stark, sometimes shaky, suggesting a cartoonist more interested in an overall picture than details. It forces the reader to complete much of the information provided in the comic strip mentally and is in tone with the pantomime aspect of the work. Readers are asked to fill-in the blanks.

This reviewer believes that it is the charming nature of the pantomime and their extensive reliance on storytelling that propelled Mackay and Oliveros to elevate Doug Wright as Canada’s master cartoonist. However, the stories contained in this volume had little to say and are not memorable. However, what is revealed by omission in Wright’s work, is the elitism and contempt English Canadians felt for their fellow French Canadian brothers. This contempt continues to this day in the Doug Wright Awards that Mackay established in 2004 as a prize for the best Canadian cartoonists. In Mackay and his associates’ world, French Canada only exists if it’s translated. The apple rarely falls far from the tree.

Rating: 6/10

Related Articles:

The Doug Wright Awards 2010

Does Canada Need a Master Cartoonist Like Doug Wright?

The Collected Doug Wright Vol. 1

The Doug Wright Award – Minority Report

Doug Wright Nominees Announced

Doug Wright Awards Return