Classification and Comics

By Hervé St-Louis

January 23, 2013 - 11:45

|

Classification taxonomist Robert Sokal argues, is an act that humans, animals and possibly plants practice. We differentiate entities according to many traits or schemes. Some argue that classification is innate and may reflect nature. Some argue that we construct categories. In the case of comics, classification is potentially completely constructed, or should I say artificial. Affirming this may help avoid conflicts and tensions about what is a comics and what is not. What belongs to comics or not is the first question that comes up when one thinks about comics and classification. In another word, I’m asking what is a comics? This is the first class, the first differentiation, the first attempt to make sense.

Here are three ways that we can use to classify what is a comics and what is not. The first one is based on a philosophical perspective called essentialism that was inspired by Aristotle and reinforced by Descartes. There is an assumption in Aristotelian classification that every entity in nature has an inner essence that determines where it belongs or not. For example, if you spot a cat with three legs, you will still classify the animal as a cat, whether traditionally a cat has four legs. There is an essence to what it means to be a cat that one just recognizes.

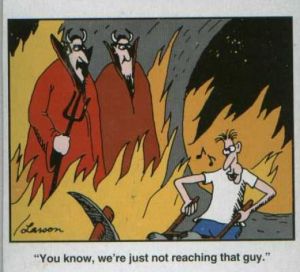

To some extents, looking at a say, a comic strip of Peanuts may generate the same reaction in you. You’ll tell yourself, this is a comics. Looking at a still illustration of the Far Side may generate in some people the same reaction. They would dump the cartoon into the comics’ class. But others, following Scott McCloud and other comics theorists would say that a single caption of the Far Side is not a comics. It is comic art based on cartoon stylings and renderings. But it does not have the sequential traits that they use to classify what is a comics or not.

The definition of comics as defined by Scott McCloud in Understanding Comics states that for a comics to be a comics, it needs to have a sequence of at least two images with an element of closure between the two visual captions, where the mind must fill in the gaps to explain the transition from one drawing to another. This kind of definition reminds me of what British philosopher John Locke would say about the essence of comics. If he could peak close enough with a microscope, he could see the underlying bits that shape a comic book. In a sense, arguing that a comics is build from at least two parts may be a Lockean way of finding out the parts that create the essence for an entity.

But there is another way to make classifications. This classification scheme is called cluster analyses. It looks at a cluster of traits which may or may not be shared systematically within the entire class defined as comics but with enough overlaps. In that perspective, the Far Side cartoon may very well be a comics because it shares enough traits with other comics such as Detective Comics or Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy. The Far Side is not generated as sequence of illustrations, yet is perceived as a comics nonetheless. Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein argues that the relatedness and the family traits between individual entities matters more than differences. One example he uses is the class called games. Scrabble and Monopoly are games, specifically board games. But baseball and softball are also games. Poker and Blackjack are card games. All these games are part of one family and share similar traits without sharing the same essence.

|

The comic strip, in this historical approach to classification would be the source from which comic books came from. Based on this proposition, animated cartoons could also be branded comics in that they were created much the same way by cartoonists such as Winsor McCkay that worked on comic strips like Little Nemo in Slumberland. Their sequential qualities and inked lines are very reminiscent of illustrations stemming from comic strips at the time. Hence, I’ve committed the biggest heresy in the field of comics and animation by lumping the two fields together, like all these lay people who can’t tell the difference between the two media! Except in my case, I’ve done so through a philosophical inquiry based on historical classification!

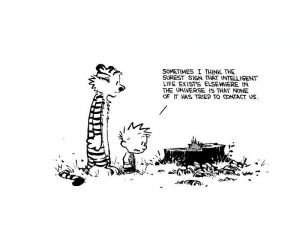

Of course, since comics are man-made constructs, their classification can be modified and argued without any certainty or definitive position as long as the classification scheme used can be defended. In the past, I had a more stringent and restrictive view of what comics and sequential art were, influenced mainly by Scott McCloud. But classification, although many claim is natural because living organism instinctively just classify their environment into entities may be a very artificial activity to respond to a natural world where dividing lines can be reshaped by thought.

Related Articles:

The Design Philosophy of the GI Joe Classified Vamp

Analogue versus Digital Teleportation: The Philosophy of Space

The Philosophy of Comics

First Look at Philosophy Behind "Green Lantern" Timed for Release with Movie in June

Philosophy and Comic Books