Backissue Retrospective: Grant Morrison and the Gospel of Batman

By Dan Horn

June 28, 2012 - 13:17

|

The instant which sparked this article was very recent actually, though I'll be digging deeper into my back-issue annals in a bit. In the debut installment of his second volume of Batman Incorporated, Morrison, via Chris Burnham's gorgeous panels, presents a gruesome scene in which Batman and Robin bust a Leviathan-run slaughter house. Between panels of the father-son vigilante duo incapacitating goat-masked Leviathan agents are disturbing images of cows being slain in quick succession, bled-out, and gutted. From the goat imagery to the ritual sacrifice of calves, this scene has several symbolic implications, foremost a religious context whose broader parameters I will be examining, but it seems here Morrison is picking at a certain psychological scab. Are copious amounts of gore acceptable when they do not distinguishably originate from human bodies? It is a question that begs an immediate visceral response from its viewer and one that thumbs its nose at the inconsistencies and unviabilities of comic book rating systems and censorship. Morrison's subversion here is of a more subtle stock relative to his mature readers books because of Batman Inc's somewhat mainstream manacles, but because of Morrison's prerogative to supplant normative storytelling constructs, that subversion remains ever present.

|

For that matter, Morrison's current Batman saga, spanning the gargantuan run of Batman (Volume 1) #655-658, 663-683, and 700-702, Batman and Robin (Volume 1) #1-16, Batman: The Return of Bruce Wayne #1-6, Batman: The Return, Batman Incorporated (Volume 1) #1-8, Batman Incorporated: Leviathan Strikes!, and Batman Incorporated (Volume 2) #1-present, seems like little more than a deliberate and picaresque pastiche of the long-form comic tale. The staggering longevity itself of the saga makes the story, each chapter almost inextricably linked back to the beginning, difficult to follow, and its mining of decades of obscure continuity minutia beyond Morrison's own influence is enough to make a seasoned comics reader's head spin. Even the reboot of DC's continuity has done little to rein in Morrison's neurotic experiment in comic book convolution, leaving his Batman Inc as perhaps the only series unscathed by the line-wide retcon despite inclusion of or allusion to characters that no longer exist in DC continuity (Stephanie Brown, Kathy Kane, Jezebel Jet, etc.).

|

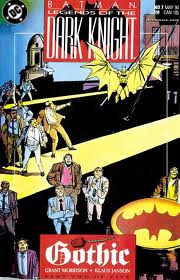

Morrison's relationship with Batman began long before his current run, with his and Dave McKean's best-selling Arkham Asylum graphic novel and the Legends of the Dark Knight arc which I'll be focusing on for a moment, a five-issue story entitled "Gothic" or "Gothic: A Romance" with art by Klaus Janson. "Gothic" took full advantage of the continuity-free Batman book in its fledgling months, exposing mainstream audiences to a berserk, satanic fever dream as the unsettling story explored among many motifs the Faustian immortality pact. For our purposes, it's worth noting a particular Janson cover in this series, Legends of the Dark Knight #7, as it relates to Morrison's Batman now. The cover at first glance seems terribly odd, incongruous when compared to the fairly commercial illustrations promoting the other four issues of "Gothic." An abstract, unbalanced composition with no clear point of reference, an imperfect linear perspective, and subtle hierarchic scaling, it certainly wouldn't appeal generally to the average comic reader. However, the image does evince something familiar, the religiosity and symbolism found in 15th Century Northern European paintings.

|

The background of the cover illustration contains in the right corner a modern, brick, curtain-wall structure and toward the left corner the parapet of a Gothic-revival cathedral. This in particular seems to indicate a parallel of relative time periods: past and present or the post-modern United States and its devoutly religious roots in Europe and colonial America. Through the foreground of the image, criminals are scattered across a rooftop like the somber and beleaguered denizens of hell in a Hieronymous Bosch piece, an inverted Batsignal dominating the bottom right corner like some heretical upside-down cross. Just below the upper right corner is the signal's converse, Batman, weirdly illuminated in the shadows between two rays of light, the only hope left for the criminals who have gathered on this rooftop to summon him, yet seemingly so far removed from them spatially, as if Batman exists on some other plane apart from those around him. This image conjures occult tonality and presages Morrison's radical presentation of Batman as a Christ figure.

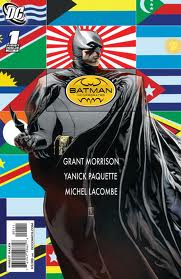

We see these classical art motifs once again in J.H. Williams III's cover illustration for Batman Incorporated (Volume 1) #1, where Batman, standing before a collage of national flags, is crowned by a Japanese rising sun, like a plate halo adorning Christ in Gothic portrayals. The same literary motifs appear time and again as well, most notably in the death and resurrection of Bruce Wayne, Bruce's post-mortem excursion through time-space reflecting the assertion of the Apostles' Creed that Christ descended into hell after his crucifixion and the institution of Batman Incorporated perhaps being an analogue of Christ's disciples taking the Gospels abroad after the Ascension.

|

This deification of Batman and strict adherence to scriptural structure might at first seem an implication of Morrison's personal religious fervor, but that is not quite the case. Rather, Morrison handles the transfiguration motifs like an extension of myth, a modern meme of an old god, in much the same way Arthurian legend is continually repackaged and retold, through stories like Star Wars, to preserve its thematic essence yet to also present it to progressing audiences. The identification alone which Morrison makes of the Christ figure as myth is striking, and his assertion that comic books should be the modern torchbearer of that myth is equally eyebrow-raising.

|

In this way, Morrison sees his own work on superhero comics as a manipulation of that mythic fabric rather than mere storytelling solely for the sake of entertainment. His addition of Batman to a long line of resurrected messiah cognates, which includes Osiris, Achilles, and of course Jesus of Nazareth, is profanely amusing in that the addition is meant to be a literal transfiguration of a mythic figure rather than a literary transfiguration of an admittedly fictional character or analogue, such as Sydney Carton or Harry Potter.

The question is, with the death and resurrection already out of the way, what comes next for a Christ figure, the book of Revelation? One thing is certain: It will interesting to see what Morrison envisions as the messiah's unwritten act.

Interested in reading more Backissue Retrospectives? You can find the other editorials in this series on ComicBookBin's Back Issues page.

Related Articles:

Z2 To Release The Doors "Morrison Hotel" Graphic Novel In October

The Anatomy of Zur-en-Arrh: Understanding Grant Morrison’s Batman

ComicBookBin Writer Zak Edwards Writes Master Thesis on Grant Morrison’s The Invisibles

Grant Morrison has been stealing my ideas, too!

A Retrospective On Grant Morrison's Doom Patrol

What Really Happened At Morrisoncon

The Binquirer, July 25 Edition: Grant Morrison quits superheroes, Chik-fil-A fails to spin Henson Co announcement, Christian Bale visits Aurora, and much more!

Backissue Retrospective: Grant Morrison and the Gospel of Batman

Grant Morrison’s Superman: Work Boots or Jackboots?

Grant Morrison on Action Comics at SDCCI