- Comics

- Comics Reviews

- Manga

- Comics Reviews

- European Comics

- News

- Comics News

- Press Releases

- Columns

- Spotlight

- Digital Comics

- Webcomics

- Cult Favorite

- Back Issues

- Webcomics

- Movies

- Toys

- Store

- More

- About

By Leroy Douresseaux

May 7, 2006 - 20:17

|

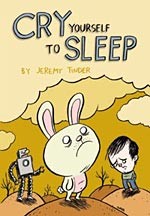

Jeremy Tinder’s CRY YOURSELF TO SLEEP follows three characters: Jim, a yellow-furred anthropomorphic rabbit who can’t keep a job to pay his rent; Andrew Saturday, a failed novelist; and The Robot, a machine who wants to be a better man. Jim goes back to his parents (a rabbit mother and a human father) for financial help; Jim’s friends give him advice on improving his recent novel (he probably needs a date), and The Robot follows a bird, hoping to learn something from the bird’s simple life, which revolves merely around survival. As they struggle with disappointment in their early adulthood, they may also be missing the bigger picture of human companionship and connection.

American comics aimed at young adult readers have generally avoided the unpleasantness that can be real life – focusing on some kind of sub-genre of fantasy. Even manga, which broaches topics as diverse as self-mutilation, depression, substance abuse, youth violence, etc. often does so within genre constraints (as the recent American version of Rozen Maiden can attest). With a mixture of sweetly melancholy humor, quirky characters, and matter-of-fact bluntness, Tinder takes a look at the hardships of life, both minor and major, in the context of a life full of wonderfully supportive people.

Without preaching and with sly subtlety, Tinder tells us that as long as we have a helping hand, the tedium and trials of life are, if not small, then, not so major that they can’t be surmounted. As a cartoonist, Tinder’s style is as accessible as a daily comic strip, and like For Better or Worse, he doesn’t offer pat solutions to problems. Disappointment exists, and there is often no way to fix things. The beat goes on, and so must we.