Comics /

Cult Favorite

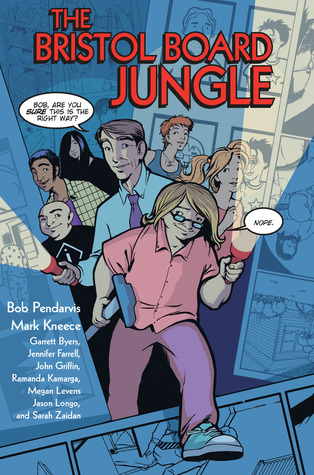

Tales From The Bristol Board Jungle!

By Philip Schweier

February 20, 2004 - 08:21

They say the streets of Hollywood are paved with dreams. So it is true in Metropolis and Gotham City, as many a young comics fan has hopes of someday breaking into the business and becoming the next Alex Ross or Stan Lee. But where does one begin? Two professors at the Savannah College of Art & Design (SCAD) may have an answer.

This month sees the release of

The Bristol Board Jungle, a graphic novel which chronicles the education of aspiring comics professionals. The 144-page black and white book is available from NBM Publishing for $11.95.

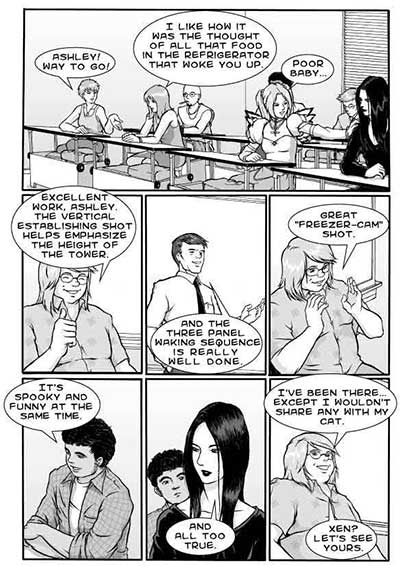

Created by sequential art instructors Bob Pendarvis and Mark Kneece, the book is more than a story of would-be comics creators and their professors. The project also serves to give some of the students in SCAD’s sequential art program experience on a professional level. Six students were chosen to illustrate the book, each in their own unique style. “Some people draw more realistically, some people draw more cartoony. It’s just a variety of styles that go through each chapter,” said Kneece.

SCAD’s sequential art program is one of the first in the country, established over a decade ago by Pendarvis and Kneece. Nevertheless, they avoid the implication that because of their combined experiences they know everything. The cover – illustrated by fellow professor Julie Collins – depicts the two instructors leading their students through a darkened maze of comics panels. “Bob, are you SURE this is the right way?” Kneece asks. Pendarvis responds unequivocally: “Nope.”

Beyond the humor, it reinforces that the book is not THE answer, nor is it a “how to” formula. “One of the things that Bob and I were kind of reacting to is that a lot people think that there is some kind of magic spell or magic pill that we can swallow that suddenly is going to make them great. It’s not a matter of ‘If you’ll tell me how to do this, everything will fall into place.’ That isn’t usually the way it works.”

“With a lot of comics artists, they don’t go to college at all,” Pendarvis adds. “They say you learn how to draw comics by sitting at home and learning how to draw. Then you send your work in and you get published. We’re saying there is another option.

“You can actually come to a friendly environment that exposes you to lots of other alternative ideas that would have never entered your head by itself. That would only happen in an environment where you would meet hundreds of other people, and then meet hundreds of other people in other majors.”

While featuring anecdotes of art classes, visiting lecturers and comic conventions, the story also serves to explain some of the nuts and bolts of creating comics, such as script writing, layout and character development. However, serving as a learning tool for people interested in a career in comics is only one facet of the book

Pendarvis feels that by labeling

The Bristol Board Jungle a textbook for a class limits it to that class. “To me it’s more of supplemental reading. It doesn’t necessarily correlate to specific lesson plans.”

Kneece agrees. “I think you can look at the book and get a lot of its basic techniques and exercises and things like that that will make you a better artist and a better writer. If you’re reading our book and you’re paying attention, you will understand it’s not all that subtle either.”

The book has been a goal for both professors since the sequential art major was established. “Mark wanted to do a textbook pretty much as soon as we started the major, and so did I,” says Pendarvis.

“Back when I was a SCAD grad student, my master’s thesis was originally going to be a 200-page graphic novel,” he says. “It was going to be about the history of comics and it was eventually going to involve the idea that in the future this will be taught in school, and it was going to get tied into my thesis. But that whole idea was vetoed.”

Meanwhile, Kneece was approached by Phil Amara, who was with Kitchen Sink at the time. “He asked me if I wanted to do a book specifically about writing comics.”

When

Understanding Comics by Scott McCloud was published in the early 1990s, Pendarvis was frustrated at missing an opportunity to feature the philosophy and theory of doing comics in a broader sense, but all in a comic book form. “We started the major, and we got to do other things,” he said. “It was Mark who said, ‘Hey, I’ve got a publisher that’s interested in doing a book about writing comics.’ So we both were working on separate ideas, but we came together.”

“I remember we spent several summer evenings over dinner, taking notes and coming up with characters and ideas about what we wanted,” Kneece continues. “Every time we would talk about it over a period of time, we would revise certain things about it because we’d been doing it longer and we had more things to talk about.”

“If that first book had ever come out,” Pendarvis says, “it would’ve been based on relatively limited experience of teachers. By doing it this past year, we had the weight of history behind us.”

In 1998, Scott Hampton was invited to visit the school and conduct workshops. Kneece relates how the guest artist contributed to the what would become

The Bristol Board Jungle. “Scott came and he did

Confessions of Cereal Eater for NBM. Scott was acting as editor and he got students – I think there were 12 in all – who contributed work to the book and it came out as an anthology. So basically the idea had been set up that we could have a group of students do work that a publisher would publish within a class here at SCAD. So that kind of set the model really for what Bob and I would end up doing.”

Pendarvis, consulting with Kneece, selected the artists to work on the book. “Our number one criteria was ‘Are we sure all these people are capable of doing it?’ “ he explains. “In other words, ‘Do we trust them to take on this job and not let us down?’ ” He cites factors such as confidence and a professional attitude as considerations in their choices.

Also integral to the artists they chose was a willingness to listen and accept constructive criticism. “Since we were going to say ‘That’s a great page. It could be better,’ I couldn’t have any prima donnas.”

The style of each illustrator’s artwork was matched up with a suitable chapter. For instance, Jay Longo, who illustrated the final chapter, was chosen for his attention to detail. “The last chapter is in a convention environment,” Pendarvis says. “I said, ‘I want robots and Klingons and giant, cool stuff, and this all takes place inside a hotel, so I want to see the scale.’ “

“Then I illustrate the so-called ‘student’ artwork,” he adds.

Based on the story, Pendarvis gave the students very rough thumbnails which they used to create the pages, applying their own style. Guided by the instructors, revisions were occasionally necessary, with some of the students redrawing things for various reasons. “I think people learned a lot from doing that,” says Mark. “Everybody that’s been involved has put a lot of effort into it.”

Both authors are quick to credit their assistant editor for taking on some of the production chores of the book, such as lettering and toning. “The hard work was done by Jen Farrell,” says Mark. “She worked her behind off on this book, so she deserves a lot of credit. She was a godsend.”

Farrell, a graduate in the sequential art program two years, says working on The Bristol Board Jungle was very positive. “It was a good experience to work with all these people and to coordinate all that was going on. I hope to get some more professional experience with editing. I want to go on to do more publishing and editing in the future.”

Farrell, who holds an undergraduate degree in graphic design from the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee, has now graduated from the master’s program and is job searching with major publishers. “But I will definitely be continuing my own art, my own stories,” she says.

In addition to her assistant editor duties, Farrell also illustrated a chapter using computer-generated art. According to Pendarvis, this drew the ire of some of the other illustrators, but he defends his decision. “A computer is just another tool. Everything else in the book is pen and ink, or Sharpie marker, but computer art definitely deserves a place in the book.”

Another ambition of the book is to dispel some of the preconceived notions regarding comics, such as the concept of comics as a boys-only club. “If you look at most mainstream comics,” says Pendarvis, “it’s guy, guy, guy, guy, OH! A woman – How nice and token. I didn’t want to have the token female artist that did a chapter. There are all kinds of ways to do a comic book. One way is to embrace an entirely different gender which most artists aren’t. I’d love it if some kid who might ordinarily dismiss girls doing comics thinks, ‘Well, damn, I didn’t even realize that was a girl artist and she’s good.’ ”

He also hopes exposure to different cultures will help readers rethink their idea of what is appropriate comic art and what isn’t. “In our classes you’ll meet other people, some of them female, and Americans will meet people from England, Australia, Indonesia. So it’s neat to see something and say, ‘I would never draw comics like that,’ and someone says, ‘In my country, that is the main style.’ “

Comic book professionals have already demonstrated their enthusiasm for a book such as The Bristol Board Jungle. According to Kneece, a number of comics creators feel that it’s a concept that nobody’s quite tackled before.

“The reason a lot of professionals that we talk to like the idea of the book is because they’re at conventions, looking at portfolios, and a lot of times they see the same people over and over. They’re always telling them, ‘You need to do this or that.’ Then the people come back later and they haven’t or they argue with the professionals, or they misunderstand their genius or something. What we’ve tried to do all along with this is try to address that issue, of how people see themselves and how they can try to reconcile that with the work they’re trying to do.”

Pendarvis hopes the positive buzz they’ve already gotten will continue. “I’d like to get the kind of response I’ve kind of pre-gotten from people like Walt and Louise Simonson, and Mark Schultz, and Bob Burden, who say, ‘I just love the concept of that book. That’s such a great idea. I can’t wait to see it.’ I just hope we meet their expectations.”

Scott McCloud’s

Understanding Comics has been praised for its thoroughness on the theory and philosophy of comic book culture.

The Bristol Board Jungle builds on elements already established, but is different in that it is told in a more narrative format. “Having taught,” says Kneece, “Bob and I thought, ‘What about practical?’ – When you’re dealing with some hardheaded student who says, ‘I insist that I am good and this is what I’m going to do.’ My thing is how to actually reach a person like that and show that maybe they need to consider some other things.”

At the same time, the book avoids step-by-step instructions. Kneece says, “It’s one thing to tell somebody, ‘You should do lines this way,’ or ‘You need to write that way,’ or ‘You need to set panels off like this.’ What do people do when they start scratching their heads and actually doing that? Most books kind of leave that in the shadows, suggesting that if you’re a perfect person in a perfect world, you’ll do exactly what we say. What we’re talking about in the book basically is what real people do when they’re confronted with these things.”

“When you read our book the first time you might think ‘I either liked it or I didn’t,’ ” says Pendarvis. “But you could read it several times and find yourself thinking about stuff you didn’t even realize were that important, and remembering it more than the thing that was actually said in front of the classroom. It could be a conversation between two students, or a connection between chapter one and chapter six.”

Pendarvis says by avoiding a lecture in comic book form, such subtle lessons enable the book to work as a simple narrative. “There are all kinds of moments in the book where you can read the book once and you don’t notice certain things but you read it two or three times, and there’s another message we snuck in. So a lot of the messages are in between the lines.”

One message in particular that Pendarvis and Kneece hope readers will understand is the book has an appeal beyond the realm of comics. Kneece suggest that anyone with an interest in the teacher/student dynamic will appreciate the book. “Even if it’s not art school necessarily, just any kind of environment where people are learning from somebody else. It would be an interesting read just on that level, I think.”

“It’s a little bit about how to teach as well,” he explains. “You’re not looking at a group of students as a group of people who are all exactly the same. The teachers are taking into account that the students have individual strengths and weaknesses.”

Pendarvis feels that learning is not restricted to a school environment. “Maybe students are not paying enough attention to each other, that they’re believing that as long as they have a good relationship with their teacher, that’s good enough. You need to have a good relationship with everyone in the class, and it might be the person that you respect the least that gives you some little insight that you weren’t expecting, that came out of left field. Because you are in a classroom setting, you are exposed to that person.”

Pendarvis also sees the book as an effective recruitment tool. “If you’re interested in teaching, or if you’re interested in going to art school in general, this gives you a sense of what it’s like to be in an art class. I want to try to get it into the hands of high school teachers around the country who can turn their students onto the idea of considering art school as an actual serious choice,” he says.

Kneece agrees. “I think people have something of a stereotypical view of art school as being a kind of a lame place where you go and some professor walks in and looks over your shoulder, and says, ‘Eh, that’s not so good,’ and then wanders off and doesn’t think about it any more.”

“Basically we’ve had to invent classes and we’ve had to come up with things that maybe no one has ever done before and we’ve had to put a lot of thought into it. That means sitting down and thinking about what the goal of this book is suppose to be, what do we need to cover here, what are the important things that people need to do. The point I guess is that it’s not the lazy professor scenario. We actually care about what you’re trying to do and how you’re trying to do it.”

Kneece also feels that comics as an academic subject in college has been overlooked. “I’ve heard so many stories from so many students who say that back in their high school, the teacher hated this stuff. The idea is that this is something that maybe high school teachers would read and it might inspire them to give a little more credence to comics in public schools before a student even gets to art school.”

The Bristol Board Jungle puts the spotlight on teaching comics. “If they read our book with an open mind, they might realize it’s more complicated than they thought,” Pendarvis adds.

“We also imply – if you’re reading the book with a brain – you start to imagine all the things we could conceivably be teaching, and that brings attention to our major. So it would be neat if other people were to read the book and be convinced to give the sequential art department at SCAD a shot.”

For more information, check out their website at

https://www.scad.edu/academics/programs/sequential-art.

Last Updated: March 3, 2025 - 20:40