Comics /

Cult Favorite

Storytellers Weekend, pt. 4 of 8: The Paradigm

By Philip Schweier

March 24, 2010 - 08:06

On Feb. 19 and 20, the Savannah College of Art & Design hosted Howard Chaykin and Klaus Janson, who presented a two-day seminar originally conceived for Marvel Comics. The purpose of the seminar is to introduce new comic artists and Marvel editors, some of whom come from an editorial background and lack the experience to effectively judge comic book techniques, to basic tools of effectively telling a story in the comic book form.

“The paradigm in this case is the basic idea of what we do,” Chaykin explains. He got it from Rik Estrada, an artist who did a great deal of work for Marvel and DC Comics in the 1970s. “Not that this the only way to layout a page, that’s where your creativity comes in, but this is boiled down to layman’s terms. We’ll start at the top.”

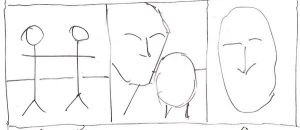

The top panel is called an establishing shot. “It’s horizontal for a reason,” says Chaykin. “Horizontal panels exist as a means of conveying lateral information. Cities and other locations are usually horizontal. Buildings may be vertical, but the cities spread outward as landscapes.”

Chaykin points out there are three levels of depth in panel one. “In the foreground there is a tree. In the middle-ground there are two figures. We’ll call them Dick and Jane. Dick is on the left, Jane is on the right. And in the background is a building or a mountain.”

What this layout does, besides fit the horizontal shape, is it tells the reader where we are, and we’ve got two characters to deal with, and the general relationship the characters have to each other and their environment.

Panel two is called the two-shot full figure, which Chaykin describes in film-making terms as a truck-in. It enlarges the first panel using the same angle, to amplify the information received in the first panel. “We now have costume, we have posture, we have visuals. Even in the crudest drawings, we can convey all those elements. The function of this picture is to take information about our characters from the first panel and enhance it by coming closer. It is NOT something to convince someone how good you are at drawing people.”

Panel three is called the two-shot medium close-up. As Chaykin said in panel one, Dick, on the left, is in the foreground, Jane is behind him on the right. “Now the amateur,” Chaykin said, “would make the large shape the important shape, but in this case, Jane’s in the middle-ground. She’s the star of the page because she’s being framed by Dick’s head. Dick’s head is once again serving as our surrogate in the context of this picture.”

What the reader gets from this is again enhancing the information from panel two. “We have facial expressions and a better idea of how they relate to each other,” Chaykin says. “We now know it’s Jane’s story and we more interested in what happens to Jane rather than Dick, which means in panel four, a tight close-up, who’s it gonna be? Jane.”

According to Chaykin, the amateur says the function of a tight close-up is to show us what someone looks like. It’s also there to tell the reader how he or she should feel about what this cast member is experiencing. “Some of this stuff is really obvious, but what gets lost when you’re doing a job is juggling all this stuff at the same time. That’s really the issue. It’s all this stuff. It’s balance, it’s organization.”

Panel five is called the return. “It’s very much like panel one,” Chaykin explains, “but the function of the return is to bring us back approximately the same deep space as that first panel. We pull back for action. In a Western culture, we are a three-point culture. In a joke – set-up, middle-ground, punch line. We deal with things in threes. That’s why there are three tiers, and three panels in the middle.”

What Janson finds fascinating in Chaykin’s paradigm is that it touches on all the important concepts that comic artists use to tell a story. “For instance, by panel four we realize that it’s Jane’s story but there’s a set-up before we there. Panel three kind of hints that it’s Jane’s story, and that’s confirmed by the close-up in panel four.”

Janson goes on to say one of the most important things is the relationship between set-up and pay-off. “There is no ability to reward the reader with a pay-off unless the situation is set up first.”

For example, if a character in panel four walks through a door, that door needs to be established before panel four. “You can’t pull stuff out of the air,” explains Janson. “You have to embrace the reader and gain their trust and be reliable in the way you communicate information to them. So again, if somebody pulls out a gun in panel five, those elements have to be established before they use it. I would never have somebody walk through a door, unless that door was already established before they actually walk through it. It’s important to establish a relationship between you and the reader, and that relationship is one of trust.

“That’s one of the reasons why this is so difficult – there’s so many things to juggle and so many things to think about. Establishing you environment and setting up things that the characters use later on is only one of the many things you have to consider.”

Janson says he approaches a page very individually; each with its own set of problems. “I start from scratch because I think every scene has it’s own set of problems, and every panel has it’s own problems. There are certain things that you’ll find you’re going to draw over and over again – somebody sitting at a computer. How do you make that interesting for the hundredth time that you’ve drawn it? So there are certain things that are going to be repetitive but I really think that each vignette or scene works best if I approach it new and fresh and don’t resort to things I’ve done already.”

Regarding Chaykin’s paradigm, Janson also emphasized that while it may become apparent it’s Jane’s story in panel four, the set-up is in panel three. Sequential storytelling is all about relationships. “It’s the relationship between and among images, the relationship between compositional choices. It’s the relationship between black and white, between large and small shapes. It’s about the ability to put things together, and in a lot of ways each panel is a small fragment of information and the only way that a reader is able to understand, and for your communication to be successful, is if those small fragments have a relationship. If they don’t have the ability to relate to each other, they become isolated bits of information that don’t add up to anything.”

The practice of sequential narrative, whether in film or comics, is addition – your ability to add pieces of information into a larger whole.

Chaykin summarized by saying, “It’s all about units. It’s all about individual units of information. Everything in this paradigm is a unit; the panel is a unit of the page, and the page is a unit of the story.”

Next Time: Panels & Relationships

Last Updated: March 3, 2025 - 20:40