- Comics

- Comics Reviews

- Manga

- Comics Reviews

- European Comics

- News

- Comics News

- Press Releases

- Columns

- Spotlight

- Digital Comics

- Webcomics

- Cult Favorite

- Back Issues

- Webcomics

- Movies

- Toys

- Store

- More

- About

By Geoff Hoppe

March 6, 2009 - 10:21

I come to bury Watchmen, not to praise it. No, seriously. I didn’t like Watchmen.

This makes me something of a pariah in the comic book world. Watchmen is regarded (not unfairly) as the pinnacle of the sequential art medium: rich with reference to superhero tradition, gripping characters, and a narrative with the inescapable momentum of myth, Watchmen is a work of such pressing immediacy that, like Impressionist paintings or great jazz, it engages both expert and novice, self-styled subversives and “banal” bourgeois. Time magazine named it one of the 100 best novels since 1923 (condescendingly referring to Watchmen’s “ambitions above its station”). That popular approval multiplies exponentially among comic book fans. Watchmen is that rare comic you don’t have to be embarrassed about liking. Saying “I don’t like Watchmen” in the middle of a comic book store is a bit like reading Hemingway in the middle of a NOW meeting: it’s not guaranteed you’ll suffer physical harm, but it’s a wise idea to have your will made out ahead of time, just in case. The suicidal loyalty it commands makes trekkies seem tame by comparison. Which is kind of odd, given that Moore seems to view his fans as little more than cat piss.

|

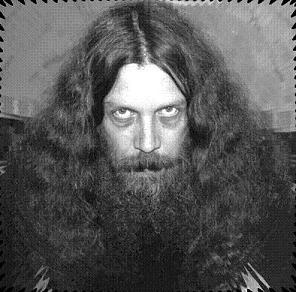

| Profile ElderGrigoryxoxo at match.com. |

If this is the case, why is Watchmen so popular? The question is, of course, rhetorical, because Watchmen is superb technique-wise. It’s funny, exciting, emotional, meticulously well-paced, multi-layered and somehow maintains all these qualities over the course of a lengthy narrative. I could illustrate a lot of instances from Watchmen, single scenes even, that outdo the total output of a lot of other comic book writers (or novelists, or tv writers, or…). But appreciation’s been done. There have been plenty of online reviews of Watchmen, and the release of the movie today will make for many more. The predictable tsunami of mainstream criticism gurgles and starts to rise. The Financial Times even published an embarrassingly hagiographic piece on Watchmen way back on February 7th, gushing over the book’s “soar of thought and reach of eschatological feeling.” No doubt other uncritical praise jockeys have already, and will continue, to appear in the coming weeks.

There are no more reviews to be written, thank God. This, then? This is not a review. This is reappraisal, complaint, criticism. This is not a review, in the ordinary sense of the word. This is an attempted revaluation of a book and a writer. The ability to appreciate a book’s strengths shouldn’t blind the reader from its weaknesses. And, Moore’s jackassery aside, there are crippling weaknesses in Watchmen people rarely acknowledge.

|

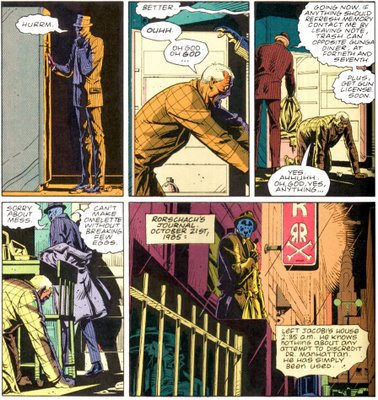

| Somehow, it doesn't scream "realism." |

Still, there are some realistic things about Watchmen. In the story, like in real life, crime is ugly, criminals are simply real people pushed into awful situations, and nothing is solved in thirty-two pages. Heroes and villains don’t always have witty retorts. They snivel, cry, or take refuge in violence, that “last refuge of the incompetent.”* Like in real life, good and evil are ambiguous. The good guys don’t always understand what they’re doing, or why they’re doing it--the “costumed adventurers” of Watchmen are less “Charge of the Light Brigade” than “ignorant armies clash(ing) by night,” a la Matthew Arnold’s “Dover Beach.” But if Moore’s story is full of moral ambiguity, it’s filled with twice as much accusation.

|

| Bring out the hell, man, and bring out the best. |

|

| Crap, if you don't want the thin mints, just SAY so... |

If people really felt the way Moore describes, comics wouldn’t exist as they do now. Titles like Garth Ennis’ The Boys (or the comic about pirates that a side character reads in Watchmen) would be the majority, rather than the exception. But they are the exception, and most people don’t buy them. People still get excited about good guys and bad guys. Sure, these stories have become increasingly ambiguous in the past several decades-- but they’re all still, at their heart, good-vs.-evil stories. Last year, the most consistently sold-out story arc at my local comic shop was “New Ways to Die” in Amazing Spider-Man, a story that paired-- guess who-- a notorious villain and a virtuous hero for the first time in awhile. Not to mention the fact that the biggest box office success of 2008 was a good-vs.-evil comic book movie. Meanwhile, Wanted, another comic book movie, did less well-- and even then, only after writers butchered and rewrote the film until it barely resembled the nihilistic, anti-heroic comic that inspired it.

|

| Don't know who made this. But it rocks. |

Whenever I read a gut-wrenching story, a voice in me says “that’s so realistic! How true to life!” That voice-- the one that equates despair with reality and brilliance--I used to mistake for my critical, rational faculty. It isn’t. It’s the opposite side of the same coin that believes, say, that unicorns are real, subsist on jelly beans, and crap rainbows. Cynicism isn’t reality. It’s the coward’s variant of stupid, unthinking optimism. Maturity resides in avoiding histrionics of either sort and soldiering through life-- in other words, it’s a lot more like Spider-Man or The Incredibles than Watchmen. If hopelessness and depression are proofs of brilliant tragedy, then Nicholas Sparks is Shakespeare and disease-of-the-week movies on Lifetime deserve Emmys. Watchmen shouldn’t be mistaken for a tragedy. True tragedy has peace at the eye of its storm, some substantial core. It was Arthur Miller who denied the idea that “tragedy is of necessity allied to pessimism…pathos truly is the mode for the pessimist. But tragedy requires a nicer balance between what is possible and what is impossible.”

|

| How does Melinda Gebbie resist him. |

P.S. And remember kids, all those nasty comments you want to leave below = hits, and success, for this site. So thanks in advance ;)

*Thanks to Salvor Hardin, and, of course, Isaac Asimov.