Comics /

Spotlight /

Knowledge and Scholarship

A New Theory of Comic Book: Part One – The Love of Comic Books

By Hervé St-Louis

October 17, 2009 - 20:08

In my last article on Philosophy and Comic Books, I identified three biases and beliefs that I held that would be necessary to spell out and before creating a new methodology to analyze comic books. These three biases are;

- I love comic books

- The business side and the artistic side of comic books are equally important.

- Studying readers’ interaction to comic books is equally important as studying the art of making comic books.

In this article, based on the biases and beliefs based above, I will begin to spell out a new way of analyzing and studying comic books that differs from established methodological frameworks, theories and approaches. Specifically, I will deal with biases that can occur when one loves comic books.

Spelling out my love for comic book means that I spell out clearly the greater source of bias any study I undertake about comic books. It seems trivial to have to mention one’s love for comic book, but take for example the effects that this can have on the study of comic books.

Adult Comics: An Introduction, a book about comic book developments in the 1990s is the typical example of what can happen when the researcher/pundit is too close to the material he studies. In

Adult Comics, Sabin sets out to explain how comic books are more than juvenile literature. He carefully explain the history of comic books in the late 1980s and early 1990s. He explains the British school and how their contribution changed North American comic books.

In his book Sabin does exactly what I have criticized several comic book pundits of doing. He sets out to prove that comic books are not juvenile literature and that they can achieve greater cultural height than credited by outsiders to the field. This may not seem a bias to some but it is. If the study of comic book in recent times is to prove that it is a medium of equal stature and complexity in genre as other art forms and media, than there is a deterministic pattern to prove something about comic books instead of allowing for a contingency of outcome when studying them. I argued in the same essay that the quest to make comic books acceptable was also responsible for the bereavement of super hero comic books which are blamed for the juvenile bent of the medium in North America.

It is the same thrust toward making comic books acceptable to outsiders that influenced the push towards trade paperback compilations of comic books. The floppy comic book is seen as a perishable good. Its origin was as a cheap product that could be easily massed produced and cheap enough so that children and soldiers overseas could purchase them and dispose of them quickly. The perishable nature of early comic books, some could argue has remained intact in the psyche of the public and further damage the possibility of comic books as being more than disposable forms of entertainment.

The quest to make comic books acceptable has also favoured some comic book publishers and creators versus others. For example, most comic books published by Marvel and DC Comics are perceived by critics as juvenile in nature and dumped in a category called “mainstream.” Other comic books, published by “independent” creators (also known as alternative) are brandied as possible example of comic books that because they don’t focus on super hero contents and address other themes are more indicative of the literary opportunities available in comic books.

In all these cases, the search for champions of a new literary form of comic books is mandated to prove the thesis of the researcher/pundit to prove that comic books can achieve greater cultural and literary heights. This mean that comic books which may not adhere to the characteristics preferred for champions may not be studied with the same thoroughness but may be addressed subjectively when analyzed. For example, because Matt Fraction and Salvador Larocca’s

Invincible Iron Man may not be taken seriously by pundits. Work done on series which are considered mediocre creative properties by some pundits like the Transformers may not receive any attention and promotion at all. I contend that IDW Publishing’s

Transformers All Hail Megatron series is probably one of the best ever written that studies characters’ motivation intricately. But because it deals mostly with a toy property about giant robots that transform into objects, it may not receive any literary and appropriate critical analysis by proponents trying to prove that comic books are not juvenile literature.

Love of comic books can become contempt for some types of comic books. It can become hatred towards comic books that do not, superficially meet certain characteristics. Critics will contend that “popular and mainstream” comic books probably receive more than their fair share of coverage in the media and that more attention must be given to those comic books with different narratives and uncommon themes that require more attention. In terms of journalistic coverage this may be true, although it needs to be verified.

Love of comic books as a methodological bias may not be shared by all researchers and pundits. Some people studying comic books may not be enthusiasts of the medium. Can love of comic books colour research more than that performed by non comic book lovers? Bias, can be distributed equally and can creep in various places in research. Thus as a foundational element of a new theory of comic book, it is important for the comic book lover to know about personal biases and control for them in his research. Love of comic books can push the researcher and pundit to push an agenda about comic books, to highlight some elements about comic books and ignore others.

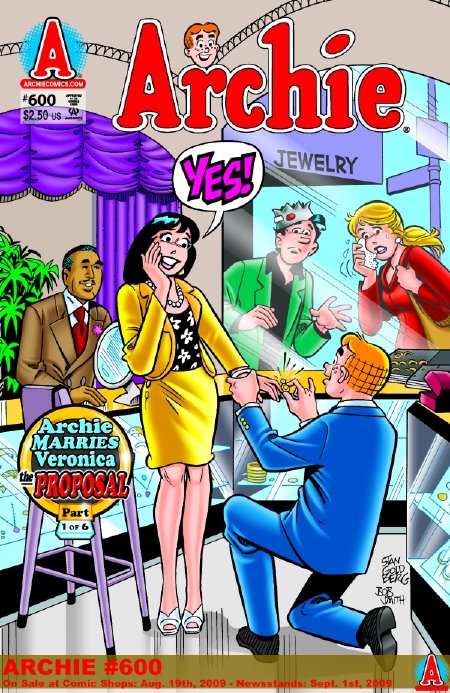

To control for biases in methodology, questions must be asked about the appropriateness of some studies. For example, studies that favour comic books written by a single creator may create a bias against comic books created by a team of creators, such as a writer and an artist. Critical studies that focus on comic books from a specific genre and publisher must explain why the specific genre was chosen and why others omitted. Was the omission caused by personal preferences, lack of primary sources, or was it conditioned by a criterion external to the comic book’s contents, such as its price, its format or availability in a specific language? Is the study focusing on comic books for girls aged eight-twelve? If so, how were the books chosen for the study picked as possible literature for that demographic group? Would it be deterministic and biased to assume that Archie Comics makes comic books for girls aged eight to twelve-year-old? How does the researcher/pundit ascertain that

The Punisher is not a book geared for girls aged eight-twelve and must therefore be removed from his study? These questions also raise the issue of the researcher/pundit’s prior relationship and knowledge of comic books. This is where existing biases can easily taint the methodological framework of a study.

There is only safe way to weed out biases. It is to be aware that they can creep in any study. However, biases as I have written before can open doors for new study avenues, when they are held as beliefs and used to ask new questions. I have such biases when it comes to thinking that the comic book artistry is equal to the business side of comic books. I’ll cover that in the next article in this series.

Last Updated: January 17, 2025 - 08:20