Comics /

Spotlight

The New Age of Comics & Culture (Part 1 of 4!)

By Zak Edwards

October 1, 2012 - 10:36

One thing that I have been thinking about for a while now is the impact of the Dark Age and the work of Grant Morrison, who has generally taken an anti-Dark Ages stance on the state of comics even when he seems to be caught in it himself. In this four-part series, I want to look at comics history, its relation to cultural events, and how we seem to be entering a new age of comics, an age perhaps predicted by comic scribe Grant Morrison but maybe gaining ground outside of comics first.

|

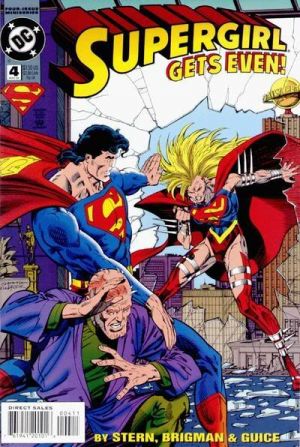

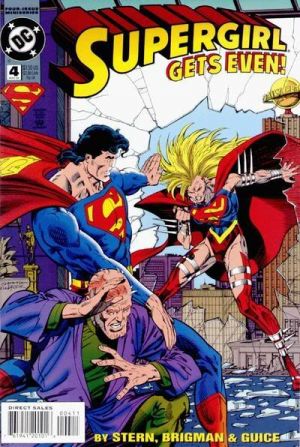

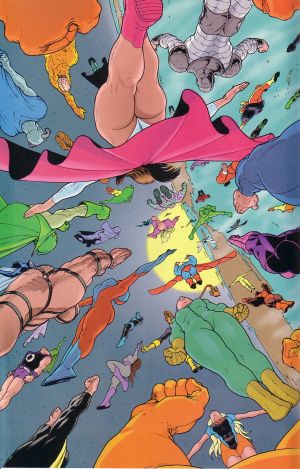

| This image typifies the Dark Age: good guys being bad, bad guys being good, and violence and sex at the forefront. |

For those of you unfamiliar with comic book history, the Dark Age refers to a period in comics generally considered to begin around 1985, when

Watchmen and

The Dark Knight Returns created a new way of looking at superheroes and their actions.

Watchmen in particular addressed the psychological curiosity of characters who want to, or are compelled to, dress up in a costume and beat people up.

The Dark Knight Returns focuses heavily on the superhero as a vehicle of violence. Both books brought the aesthetic people generally refer to as ‘gritty realism’ to comics, namely a noticeable rise in the violence and graphic depictions of superheroes who are not always good doing things to villains who are not always bad. Characters like Wolverine and the Punisher gained a renewed and continual popularity for their devil-may-care and violent approaches to problem solving and this popularity speaks to the period as a whole. The Dark Age has lasted a long time, most would argue up to the present day, as comic readers are continually fascinated by the sex, violence, and anti-heroics the Dark Age represents. Some exterior events have influenced the longevity of the period as well; the Comic Code Authority has all but lost its censoring abilities so mainstream comics can regulate themselves and the impact of the September 11 attacks on fiction fed this already present cynicism in comics. I would also tend to believe that the bulk of the DC reboot last year adheres to the aesthetics of the Dark Age, with the use of excessive violence and graphic, complicated sexual scenarios used to destabilize the good-bad dynamic of the characters (and to titillate a primarily male audience).

|

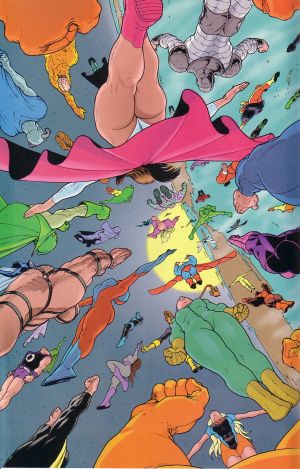

| Flex Mentallo ends with his heroes flying towards our earth at dawn. |

Grant Morrison’s

Flex Mentallo speaks to this comic history, with each issue reading and representing an historic age of comics, from the Bronze Age, through the Silver Age, past the Dark Age and towards a New Age of superheroes. The third issue, with its cover bearing a strong resemblance to the famous

Dark Knight Returns cover, is filled with superhero sex clubs, wanton violence, and an air of hyper-ridiculousness, the general tropes of the Dark Age. While most superhero books operate on a central idea of melodrama, it seems even more pronounced here and, indeed, the sex and violence of the Dark Age only seemed to intensify as it went along. The fourth issue of

Flex Mentallo, however, speaks to a coming New Age where heroes return to being heroes and comics become, to quote Morrison’s Playboy interview, “Western culture’s last-gasp attempt to say there’s a future for us.” In short, Morrison argues superheroes can be templates,

Supergods that are closely linked to their Greek roots in terms of how their believers look at them. Greek gods are humans on a different level. They are flawed, yes, but they are also handy metaphors for the human existence, identifiable because of their humanity rather than an ultimate and impossible purity. Morrison’s New Age seems to argue for both ends of the spectrum, that the heroes operate in a purely metaphorical capacity rather than spectacles for disposable enjoyment.

My question is this: Are we at this New Age and is it already being expressed both in and out of comics?

To think about this, I’m going to look at what I would call 9/11 fiction, works that express a certain aesthetic that (re)emerged after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Key examples include

Lost, The Wire, The Ultimates, The Office, and

Arrested Development. All of these works are deeply involved in and respond directly to the impact of 9/11 on our culture. There was a noticeable increase in racial profiling that led to some basic films being put out, a friend of mine argues that the

Lord of the Rings trilogy turns into a basic “let’s hunt down and kill the insurgents” plot that dominated this period, but these aforementioned works speak to a general distrust in fiction. As one person put it (and I can’t remember for the life of me who, so apologies for the paraphrase and the lack of credit) “the conspiracy theory domination of nineties popular media became real in the wake of 9/11, so fiction itself became more real.” Reality TV became huge, not only because it is some of the cheapest television to produce, but because it emphasizes a mediated ‘true experience despite the extraordinary experience of the show itself.

Survivor, for example, is about people being petty and cynical in an exotic and strange environment.

Lost came in response, and with it

The Office and

Arrested Development, shows that owe a debt to reality TV and emphasize different aspects of the current human experience.

For

Lost, the first season features many concretizations of the 9/11 mindset. For one, a smoke monster, a creature literally made of smoke that cannot be defeated, terrorizes the predominantly American cast, making the fear of the abstracted terrorist threat into something out of a horror film. Another concretization is the inclusion of a Middle-Eastern man, Sayid, who allows the audience to be simultaneously nervous about and identify with one of those who fits the racial profiling of a terrorist (in a way, the inclusion of this character is a great example of the postmodern idea of the shift between either/or to both/and; the character is both/and an expression of racism and acceptance). The show, through high concept science fiction, acts as a microcosm of the 9/11 experience: everyone is a potential enemy, the outside threat is extreme and incomprehensible, and we must all band together against this outside threat while sacrificing our rights in order to protect ourselves from each other.

The Office, by contrast, deals with the enormity of the mundane and grounds the 9/11 experience so far into the everyday that it becomes absurd. The show, about a paper company and the people who live out their lives there, is more about the mundane reasons for never reaching potential because of the most heartbreakingly real excuses. This concept works across both the English and American versions of the show; Jim/Tim stays for love, Pam/Dawn for low self-esteem, and other characters because they simply can’t afford to do anything else, making them terrible examples of the work to live and live to work problem. It’s to the point that the only people legitimately enjoying their work are absurd in and of themselves (the Dwight/Gareth character). Boss Michael/David is ludicrous but also sound like those people that read books about business and then try to act on what they learn only to sound fake and plastic. It makes perfect sense that Michael falls for a pyramid scheme in one episode of the American version because it represents both his inability and his desire to know. By contrast, Dwight/Gareth simply cannot be real, they are too absurd, and their love of their occupation makes them even more hilarious. At its core,

The Office represents the intense cynicism of the 9/11 condition and represents a place where the anxieties of the social climate can be analyzed and reasoned through in the most horrifying of ways: by making fun of the audience through relating to their own entrapment. We can identify too well at times and there is little sweetness and little innocence to the daily struggle in the little towns of Scranton/Slough.

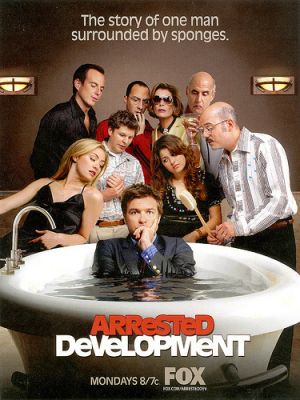

Arrested Development is possibly one of the most adept and covert analyses of the 9/11 condition in American media. The show starts off with a condemnation of the leader of a corrupt corporation and eventually tries him for treason before revealing the entire thing was a result of the incompetence of American bureaucracy. On top of all this, the show constantly refers to the incompetency of the people in charge of us or trying to direct us. Michael Bluth, the ever faithful straight man archetype, designed as a place where reason and logic can ground the wacky misadventures of the other characters, rarely ever actually accomplishes this in any episode. Mostly, he acts as the exact opposite while thinking he is this straight man amongst idiots, buying a Porsche while telling everyone to tighten up on their spending and even almost marrying a very obviously mentally challenged individual that he believes is just really into him. Many

Arrested Development episodes involve an arc where Michael is proved wrong while his family is also proved wrong, all the while pointing out to absurdity things like the military’s directed recruitment procedures (and various ways of increasing the number of soldiers), our governments’ paranoia and incompetence, and our culture’s continued distrust of immigrants.

In comics, I can think of nothing better than

The Ultimates to truly depict both the 9/11 condition and the Dark Age aesthetic. The reboot of

The Avengers into the Ultimate Universe is packed full of the cynicism and distrust that appears in comics before and after 9/11. More can be read about this in an article I published a long time ago

here, but there are plenty of examples of how the book relates to 9/11.

|

| Captain America is shown here with military weapons behind him, asking is he himself a weapon and, given the politics of the War on Terror, is he truly a hero? The answer is, as Dark Age books like to say, is complicated. |

In

The Ultimates, Captain America is a punch first, ask questions later John Wayne whose black-and-white morality leads him to constantly cause more problems than he solves. Iron Man is a charming, functional drunk who is more than willing to violate labour laws so he can have a cool proposal to his girlfriend, a white collar criminal who represents pointing the problems of conviction of white-collar crime in the United States (in one issue, Captain America hunts down a man who hit is wife but will fight alongside a man who blatantly exploits underpaid workers). The heroes operate under the US Government and are used in the Middle-East despite the promise they never will and, eventually, the Cold War literally comes back to destroy the United States and with it questions of the age we live in. The characters are bad people doing bad things (like spraying their wives with Raid) in the name of good, a constant discourse of the 9/11 condition.

In summary, the impact of 9/11 in our culture is profound and it bred an entirely new yet familiar ways of expressing ourselves through our fiction and consumption of it. Shows like

Lost expressed our internal distrust because of an external, incorporeal enemy while highlighting the classic security/freedom dialectic.

The Office, by contrast, made fun of our ultra-mundane existence while highlighting much of our anxieties.

Arrested Development pointed to our social systems and governance by removing logic and replacing it with absurdity thinking its reasonable.

The Ultimates seems to work as a bridge for superhero comics, extending the life-span of the Dark Age by talking about the New Cold War of 9/11. Overall, the 9/11 condition still exists, but I wonder about its continued relevancy, how people and are responding to the 9/11 condition, and if we are in fact at the beginning of something new.

Now that we have this groundwork,

next time I’ll talk about what lies ahead and now.

Last Updated: March 3, 2025 - 20:40