Books

Superheroes!: Capes and Costumes in Comics and Film

By Zak Edwards

August 21, 2010 - 14:19

Roz Kaveney, a fairly well known popular culture commentator, recently devoted her efforts to the superhero genre of comics and film in her book Superheroes!: Capes and Costumes in Comics and Film, which offers a variety of meditations on the superhero genre of mostly the past thirty years. The book is, in her own words, a fairly "theory-lite" but still fairly academic analysis of the genre, but not without many of the problems that come about, both with the academic pursuit of graphic literature, especially in the superhero genre, but also in the addressing of a more general audience, which may cause her arguments to become both less well-crafted, but also more simplistic.

|

Unfortunately, as I have discovered in many of the various books and scholarly articles on the subject of graphic novels, Roz Kaveney’s defensiveness of the legitimacy of the study of comic books leads to some fairly strange points, many of which are exploited in order to gain notoriety and mostly require an acceptance of a hierarchy of art. Kaveney frequently compares her experiences with comics, quite pointedly and repetitively, to her experiences with classical music, ballet, and opera; assuming these forms of art are held in higher regard and are therefore a more legitimate form of artistic expression to which superhero comic books must be compared to gain similar notoriety. These discussions reminded me of the "video games are or are not art" debates which plagued the internet a few months ago, leading to people expressing that Metroid Prime led to similar emotive reactions as reading Dostoevsky (which somehow proves a point about art and aesthetics, I'm not sure how, though). Kaveney fairs only slightly better overall in these moments, but largely her inability to target an audience leads to a book which, while filled with some very good ideas, loses more than it gains.

Superheroes! has problems finding and speaking to an audience, choosing a large demographic with material which leads to many issues of what is being said, what is being glossed over, and what is being proven. Kaveney largely chooses, in many places (even in her exercises of close readings), to display an almost encyclopedic knowledge of comic books of the past thirty years and a little further beyond while maintaining an attitude of mostly mockery of people who hold value to such knowledge. Comic book readers have generally had the problem of amassing pointless facts in order to point out flaws and win matches of general knowledge, but Kaveney has largely displayed this almost to prove her worth on the subject, mostly leading to generalizations about material and arguing contexts known only to a select few. Similarly, Kaveney argues quickly about subjects known only to a select few from an academic perspective, leading to possibly an even more frustrating quick dump of information before moving onto another subject. Her close readings, which makes up the majority of the book, suffer from this sort of summarizing while avoiding fully developed arguments to seemingly keep the audience a larger demographic. Phrases like “this isn’t as Jungian as it sounds” frequently occur before the switching of topics, hiding entire papers in between sentences. The result, unfortunately, is the everyone is no one principle and everyone is left wanting more.

|

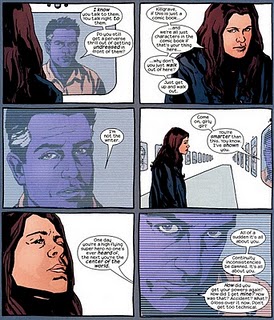

| Kaveney is particularly interested in the relationship Jessica Jones has with the Purple Man and how her past is explored through an already created history. |

Not to say Kaveney doesn’t have some legitimately good ideas and readings. Her book is filled with interesting readings of a variety of texts, especially her readings of Brian Michael Bendis’ “Alias,” Frank Miller’s “The Dark Knight Returns,” and Mark Millar’s “Civil War” (if only primarily from a publisher’s perspective). Her notion of “thick text,” which is left unexplained in this book, is helpful for considering the larger contexts in which these books exist. Her entire chapter dedicated to Alias is extremely interesting, exploring the book as both a meditation on the genre and the Marvel universe. Kaveney’s arguments against a feminist perspective are refreshing to a degree (arguing against the trend of infusing texts with a feminist critique despite there really being little to work off of), but ultimately devolves into the complaints against Marvel’s House of M and Avengers Disassembled which seems to be doing just what she is arguing against. The chapter is arguably the highlight of the book. Her Watchmen analysis doesn’t offer much to possibly the most discussed superhero book in existence, mostly reiterating points others have made. By contrast, the comic book often paired with Watchmen, The Dark Knight returns, is given a fairly in depth analysis which both highlights the beginnings of trends seen in Miller’s later works and attempts to analyze many other perspectives of the Batman tale. Avoiding the usual critiques, which basically highlight how the Batman story bucked the usual tropes of the superhero genre, Kaveney instead analyzes the text for itself, bringing some very convincing arguments and interpretations with her. Civil War is similarly given a decent amount of consideration, targeting both the extent of the political interpretations and the book as continuing the reflexivity of the superhero genre. Her promises of working through its more problematic points, however, are never brought forth, which is fairly disappointing. These close readings make up the bulk of the text and offer a great amount of contextual readings as well as interpretations of the book on its own.

|

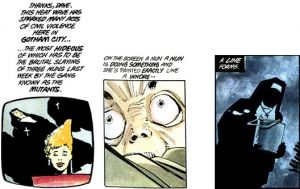

| One of Kaveney's more interesting analyses is the relationship between media, the public, and the creation and sustaining of the superhero, both as a public and vigilante figure. |

Superheroes! eventually falls apart by the end; her analyses of Joss Whedon, both his television and comics work, are nothing to be astounded by and mostly rely on already discussed comparisons between Whedon’s admitted influences and his own work. The chapter is ultimately a fruitless exercise considering the work accomplished in previous chapters and almost seems to work as filler given her previous books and papers written on Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Similarly, the final chapter on the comics-to-film industry really never draw any conclusions which argue anything at all, leaving the last two chapters of the book to really only have a brief skimming over. Kaveney also has a tendency to have her interpretations and analyses lead to both extreme points, with phrases like ‘the best book of...’ or ‘worst example of...’ frequently popping up, and the valuation of the texts based on her interpretations. The strength of Kaveney’s book ends up mostly in the first few chapters, reading certain particular sentences which hint at a deeper argument left untouched. The conclusions are ultimately up to the reader to work through the arguments which are left untouched and almost hidden. Superheroes! is a great book in theory (lite), but is too wrapped up in its apparent illegitimacy and unfinished good ideas to be fully effective. Kaveney treads a line between literary interpretation (academic) and historical recording (popular) without fully satisfying either. Worth the read, but one is left waiting for the day when a book of the scholarly consideration of superheroics is done without apology or excuse.

Last Updated: January 17, 2025 - 08:20