- Comics

- Comics Reviews

- Manga

- Comics Reviews

- European Comics

- News

- Comics News

- Press Releases

- Columns

- Spotlight

- Digital Comics

- Webcomics

- Cult Favorite

- Back Issues

- Webcomics

- Movies

- Toys

- Store

- More

- About

By Andy Frisk

January 23, 2011 - 16:46

(Being more an essay on than review of this story, there are spoilers ahead.)

Brian Wood’s realistic and engaging saga of the Viking Age circa AD 800 to AD 1300 is one of the best written and drawn series of all time. I’ve sung the praises of this series many times here at The Bin, and every time that I think that there isn’t much more to say about this wonderful series, a new issue or storyline is published and I find myself chomping at the bit to talk some more about this series and how it is an excellent example of comics-lit. Literary sequential art is not as rare as one might think. Some publishers like NBM are dedicated to only printing books that are literary like Ordinary Victories. Of course, there are books out there that exist for the simple pleasure of reading a fantasy, action/adventure, or horror story, but more and more often in the last few decades, many mainstream titles and their publishers (where most of the run of the mill escapist books come from) have really began to get serious about the art that they publish. Recent stories like The Sinestro Corps War and The New Krypton Saga are excellent examples of mainstream characters and books tackling important social and political themes in a manner that one would not expect from the spandex clad crowd. Some publishers, like DC Comics, have been brave enough to dedicate entire imprints to more discerning and literary types of books. DC Comics’ Vertigo line (another imprint that I, perhaps too oft, sing the praises of here at The Bin) is one of the best, if not the best, mainstream publisher of sequential art titles that are not only great reads, but are often great works of literature within their medium.

Brian Wood’s tale of turn of the last millennium European northlanders prides itself on demonstrating to us that the more things change the more they stay the same. This isn’t horn helmeted (or wing helmeted) Vikings, these are real and relatable to men and women living through, albeit in a much harsher and technologically primitive time, the same fears and struggles that men and women do today. Their world is often victim to rampant plague, religious conflict, and a mad grab for wealth. Many of the stories Wood has told thus far vary in length from seven issues to one. His most recent tale “The Girl in the Ice” lasted only two issues, but as a story, it encapsulates everything that is great and literary about this title.

|

Briefly, (and again spoiler alert) “The Girl in the Ice” is the tale of Jon, an aging hermit living in the frozen wastes outside of Reykjavik, Iceland in AD 1240. As a young man he fought for the ruling clan of Sturlungs, but as he’s aged his usefulness as a warrior has waned as has the Sturlungs “protection and support.” He fishes the ice ponds and ekes out a meager existence. In his own words, “soon I will die.” He is to live through one last adventure though before he passes way. Upon discovering the body of a young girl frozen in the ice he is consumed with discovering the truth behind her death, and by extension learns of the futility and at the same time rapturous nature of the age old adage “the truth shall set you free.”

The time period that Jon is living through is rife with clan warfare and political strife where everyone is suspect of something. Living on the outskirts of the main settlement of Reykjavik the warring clans demand information of him that he simply doesn’t have. His lack of knowledge is what makes him suspect. The clans don’t believe that he knows nothing. He is simply an old man waiting to die though, and the youthful warrior men can’t grasp this fact since they are ironically full of life yet so close to death themselves. When Jon is discovered with the body of the young girl, he’s accused of her murder and possible desecration. His only goal though has to been to discover the truth of her death and put her to rest, since there must be some significant reason for someone so young, beautiful, full of life, and obviously on the cusp of living a rewarding life to have been laid low and left un-mourned in the frozen wastes. The only possible clue Jon has to work with is a beautiful brooch that he finds on the girl. Jon surmises that perhaps a jealous lover has slain her and left her there among other possible reasons for her death. To Jon, this is “a crime of empowered men in a lawless land…who else could harm such a creature?”

As the story progresses, Jon really doesn’t get a chance to do any type of detective work or arrive at any evidence based conclusions beyond what he imagines are the reasons for her death until he is discovered with the body. He is brought to Reykjavik to face trial for the girl’s death. He had nothing to do with her death and the girl had nothing to do with him beyond the fact that he became absorbed in the mystery of her death. As it turns out, the young girl was the victim of no crime. She isn’t a violent, romantic, political, or dramatic victim either. The brooch Jon discovers her with belonged to her mother. The girl was to inherit it upon her marriage one day, but as young girls often are, she was impatient to possess it. The young girl is caught playing with the brooch in her mother’s bed room and upon dropping it, her mother is certain that it has been broken. It hasn’t been, but the ensuing argument causes the girl to flee from the home with the brooch. The girl essentially ran away from home after a mother/daughter fight. The mother, letting her “stubbornness drown out the fear and worry” that her daughter might freeze to death never pursued her. The girl was dead in a few days and the mother torn with grief. “The weather took her obviously,” the mother relates to Jon as he is held awaiting execution for the girl’s death. Jon’s futile attempt to discover the dark secret behind the girl’s death has lead him to the conclusion that there was no dark secret, and that the girl’s death was pointless and the result of the immature, but vibrant life that the girl possessed.

|

There are literally a myriad of literary ideas and themes on display here within this story. It really is one of those (now clichéd) examples of a work that would “tie up grad students for hours” discussing the work’s themes, ideas, etc. I myself, with my meager education in literary criticism, can think of no less than four or five critical approaches to take towards this story. The most obvious though are the most powerful: The story can be seen from a nihilistic point of view, or it can be seen from a revelatory point of view regarding the validity of the aforementioned adage “the truth shall set you free.” A third powerful theme of the story is the power of the mind to create something that simply isn’t there.

Perhaps most obviously and perhaps most superficially, a nihilistic view seems to permeate the tale. Jon is determined to find out the truth behind the girl’s death and pursues this goal to his own death. His quest for the truth leads him to it, but it is not the truth that he thought he would find. All his efforts lead to a disappointing end, and his subsequent death and the revealed death of the girl’s are both meaningless in the scheme of things. A silly familial argument and a baseless conviction for a crime not committed definitely round out a tale that (to borrow from Shakespeare) “a tale full of sound a fury, signifying nothing.”

In opposition to the nihilistic view of the story that is easily taken is a more redemptive one. Yes, Jon’s and the young girl’s death are overall meaningless as far as regards to what we expect or demand by way of our sense of justice and drama, but Jon does end up getting the truth of her death, as unsatisfying as it may be. He is condemned by the priests that nurse him back to health before his trial to hell for his sins, but Jon ends up, through death, being set free of his harsh existence. He has committed no crime and is not a pervert or a murderer. Who is to say that his fate is burn in hell (obviously from a religious point of view)? Jon does bring a final peace of sorts to the girl’s mother and in essence sacrifices himself in her place, becoming much more holy than any of the priests that tend to him. As an aside here: the views of the Christian priests and their blatant disregard for their god’s teaching, which is forgiveness, is yet another springboard that can be used to jump off into a discussion of the themes of redemption, forgiveness, and the hypocrisy of religion that are on display in the story.

Some might say that Jon’s plight is neither meaningless nor redemptive spiritually, but simply a product of his own mind. He creates his world and his plight by investing more meaning in the girl’s death than was actually there. He leads himself on that there must be some really significant reason that the girl passed away in the ice and snow. There really isn’t a complicated reason that goes beyond a family fight. He also takes it upon himself to dig her out of the ice in the first place instead of leaving her to her rest, or even notifying one of the soldiers that are constantly questioning him. His dreams of solving some dreadful murder are all a figment of his imagination, as many philosophers might argue that our whole world is.

|

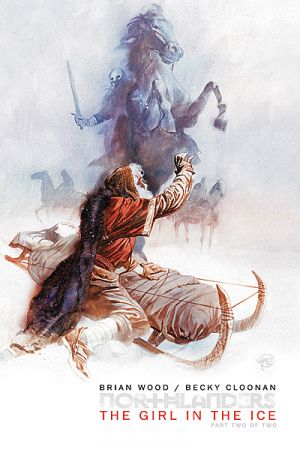

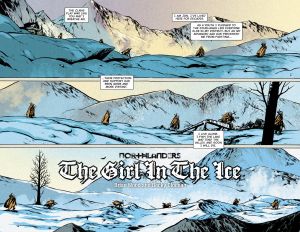

What makes “The Girl in the Ice” a truly unique work of literature though is the fact that all of the above literary themes and assertions are communicated not just through Brian Wood’s script and story, but through the medium of sequential art as interpreted by artist Becky Cloonan. Several panels successive art are completely devoid of words. The tale is told through image and atmosphere. The body language Cloonan imposes upon Wood’s characters and the vast blank and enveloping whiteness of the landscape echo both the nihilistic idea of nothing and the redemptive idea of cleansing purity. The violent visages of the nameless warriors of the Sturlungs and their rivals in battle also emphasize the universally existential struggle that engulfs all men and women in their lives regardless of their station in life or identity. The medium of sequential art used this way resembles cinematography-like artfulness, but is completely unique on its own regarding its print nature.

I know that the assertions I have made in this rather long look at what I consider to be a work of literary art range from dead on accurate to absolutely and completely wrong. I expect them to be. That is what great literature does for its readers. It challenges them to think, debate, argue (civilly), and eventually prove their assertions on the work, and by extension life, as true to the world at large or themselves only…or vice versa. There is a great amount of comic books, sequential art stories, or whatever you what to call them already published or being published, but few rise to the level that Brian Wood has taken his tale of turn of the last millennium northlanders to. While literary sequential art isn’t as rare as you’d think, as I mentioned above, we, as scholars and fans, would definitely be benefited by there being more like this.