Comics /

Spotlight /

Knowledge and Scholarship

Maus: A Comic Tale of Moral Panic

By Hervé St-Louis

February 4, 2022 - 16:49

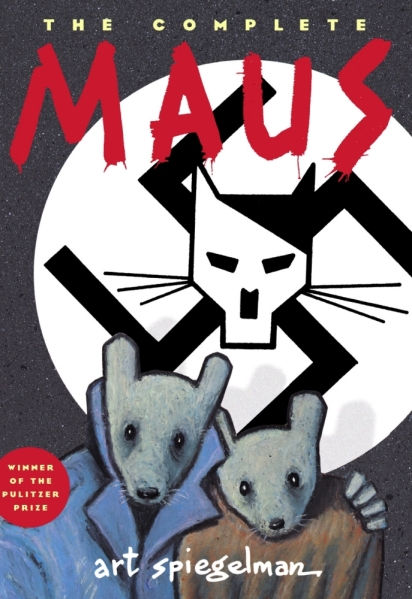

On January 10th, 2022, the McMinn, Tennessee, County Board of Education unanimously voted to remove the Pulitzer prize-winning

Maus comic from its eight grade English curriculum.

Maus, a comic strip created by American cartoonist Art Spiegelman is the adaptation of the recorded memoir the cartoonist had with his Holocaust-surviving father, initially published in

Raw.

Raw was a self-published fanzine Spiegelman published in the 1980s with his wife Françoise Mouly. The schoolboard decided to remove

Maus over concerns over nudity and objectionable language, prompting accusations of censorship by the media, pundits, literary critics, academics, and Spiegelman.

Similar censorship, banishment of comics and other forms of literature iare not new.

Maus joins an illustrious list of banned books such as

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,

To Kill a Mockingbird,

The Catcher in the Rye,

Of Mice and Men,

A Farewell to Arms,

On the Origin of Species, and many more. Comic-centered censorship has happened since the 1950s when psychiatrist Fredric Wertham wrote

Seduction of the Innocent (1954) where he denounced comics’ immorality and effects on children.

Comics as Children Literature

There is common perspective that comics are children’s literature, thus cannot broach certain topics and should be moral.

Maus, using anthropomorphic characters where Jews are mice, Germans are cats, and Poles are pigs can easily be perceived as a children’s book because of the cartoon representation of characters.

There is an expectation that children’s literature must be dumb and safe for kids. It is important to mention that being added to a schoolboard’s reading list or not also has deep financial consequences. Youth-focused book publishing is a big business, especially for comic creators. Because of the simplification of characters, and places, into universally recognizable iconographic elements, as argued by Scott McCloud, many see comics as juvenile literature lacking the serious of more realistic renderings. Thus, even though

Maus is a Pulitzer-prize winning comic strip, it is still viewed and perceived as children’s literature that must be clean, and innocuous beyond anything. It should be the equivalent, in a way to the

Muppets Babies, or anything on Disney Kids.

But many people who espouse such views about children literature and entertainment forget that traditionally, children's literature was anything but feeble and safe. Any story from

Aesop’s Fables, later adapted into countless Disney animated films and books have inherently depictions of violence, deviance, and can provoke fear, and amazement in youthful readers. A bit like watching the old tween Canadian horror television series

Goosebump, being afraid is a valuable form of entertainment.

Comics as History

But then,

Maus was never deemed purely juvenile literature. It was awarded a Pulitzer Prize on the strength of its narrative message which many forget is a serious historical account of the Holocaust and concentration camps during the Second World War, much like Hemingway’s

A farewell to Arms is also considered a historical account by World War One historians, because of its depiction of the German advance against a retreating Italian army.

In fact,

Maus is closer to a historical account than Hemingway’s novel as it features autobiographical accounts of concentration camps and the Holocaust through Jewish survivors. Comics as historical accounts have been established by scholars such as Joseph Witek as historical texts. Cartoonists such as

Joe Sacco and

Marjane Satrapi have used comics to tell stories about social and historical situations that are legitimate historical scholarship. I teach that such comics are as legitimate research materials in my research methods’ courses.

This is an important dimension of

Maus that was forgotten and ignored by the Tennessee schoolboard, and most people when they think of comics. Comics often are historical texts. Instead of just writing history, they can also be illustrated with a narrative. It is odd that taken separately, writing and illustration objects, as is often done in medicine, biology, other natural sciences are all valid usage of illustrations, and drawings, but when this becomes cartooning, often combining both words and pictures, comics are no longer valid scholarly texts.

Moral panic

Part of the reason for that is a continuing moral panic about comics where there is a need to protect “credulous” and “innocent” minds from an art form traditionally perceived a low form of culture, and potentially, detrimental to the intellectual growth of youths. Previous moral panics about comics have led to book burning. However, let us not ignore that there were comics burn by well-meaning youth and cultural advocates, as happened in the fall 2021 in Ontario, Canada.

While many pundits probably feel the need to attack the Tennessee board members and label them conservative, right-wingers, and reactionary, stupidity should be equally shared with many left-leaning adherents who also indulge in extremes about comics.

Tintin, while containing very racist imagery, as I have discussed in the past, is an important historical and cultural text about Belgian culture and society. There may be some amount of hypocrisy today about

Maus from some of its defenders who may not extend the same protection to Hergé’s

Tintin in the Congo and

Tintin in the Americas.

There is always someone that needs to be protected with moral panics and comics, much like games, and animated cartoons, are often on the edge of censorship and what some deem good taste or contents safe for kids. Comics, I often argue, come from the tradition of the cartoon (caricature), which is itself the inheritor of the king’s fool, the mad who was able to criticize society.

Thus, comics present an alternative to the usual critical traditions that stem from Marxism, while being able to espouse any ideology. That makes comics, cartoons, games, and animation subversive. They can mock anything, and anyone, not just those in power. They can also play the role usually held by the journalist, the essayist, and the scholar.

I do not seek to condemn the decision reached by the McMinn County Board of Education. No matter what their motivations were, they do not understand comics, and it is the responsibility of comic scholars and other pundits to make sure that people “get” comics. Comics are complex and their history mostly unknown.

Maus is an excellent comic that I read in 1991 when I was developing my formative thoughts about comics.

Maus is a comic strip, not a graphic novel. It was created as a serialized story told through a few pages at a time and only later was the full work assembled into collected editions. The fact that many of the pundits defending

Maus today as an exceptional graphic novel, which it is not, means that much work needs to be done to educate people.

Maus was an exceptional comic strip. It is not a graphic novel.

Comic strips have different lives than graphic novels because the magic behind their storytelling approach rests on the fact that the reader does not have access to the entire work, while perusing parts of it. Often, most of the work has not been created while the reader views a particular instalment. That is because, the unit of reference of the comic strip, unlike the graphic novel, is the page itself, not the whole work. Through one page at a time, the cartoonist must convince and engage the reader, and not rely on the full body of a work that often is not even borne out of the creator’s imagination, or notes, in the case of historical comics such as

Maus.

Maus can continue to be an important comic strip, or for purists, a sequential art work about a part of recent history that is already contested daily by deniers. The mice and the cats’ device was simple and easy for most to relate to.

Maus, like good comics and other works of literature drew from readers’ familiarity to open a breech, to tell a compelling historical account of a concentration camp survivor. There is still much to learn from

Maus.

Sources

Hemingway, Ernest. 1929.

A Farewell to Arms. New York City: Scribner.

Hergé. 1931.

Tintin au Congo. Bruxelles: Casterman.

—. 1932.

Tintin en Amérique. Bruxelles: Casterman.

McCloud, Scott. 1994. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: Harper Perennial.

Sacco, Joe. 2001. Palestine. Seattle: Fantagraphics.

Satrapi, Marjane. 2000.

Persepolis. Paris: L'Association.

Spiegelman, Art. 1991.

Maus. New York City: Pantheon Books.

Wertham, Fredric. 1954.

Seduction of the Innocent. New York City: Rinehart & Company.

Witek, Joseph. 1989.

Comic Books as History: The Narrative Art of Jack Jackson, Art Spiegelman, and Harvey Pekar. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Hervé St-Louis, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Emerging Media at Université du Québec à Chicoutimi, in Canada.

Last Updated: January 17, 2025 - 08:20