Comics /

Spotlight

Spotlight on the Louvre Collection

By Beth Davies-Stofka

June 23, 2010 - 18:57

The Louvre was the first public museum, established in 1793 when the French people, having overthrown the monarchy, nationalized the royal collection. According to Wikipedia, it is also the world's most visited museum, averaging 15,000 visitors per day.

The 20th century saw a lot of discussion about the purposes of art museums, and it has carried forward into the 21st century. The discussion remains vigorous, especially when public funds are involved.

What is the purpose of the Louvre? Is it to provide a safe home to hundreds of thousands of objects, and to take responsibility for their care? Is it to provide its visitors with experiences and encounters that are either interesting, or edifying, or both? Is it to guide, perhaps even manipulate, private and public perceptions of art? Is it to determine the outcomes of the sometimes violent conflicts generated by changing theories of art? Is it to create and mediate value? Is it to act as arbiter of good taste, and bad? Is it an outlet for the cultural elite to acculturate the barbarians of the twenty-first century, barbarians like you and me who might actually enjoy a little kitsch? Is it, to put it baldly, to make money?

The question of a museum's purpose is a wonderful one for artists to ponder, since they rely on museums. Museums provide sanctuary for studying and learning from other artists. Museums are sources of funding and publicity. Museums serve as a constant reminder that art and artists matter to a society and its people. And yet this relationship between artist and museum can be a double-edged sword as when, for example, a museum follows the money. When one artist is in favor, another is out. It's a dirty and competitive world.

In the current co-publishing project between NBM and the Louvre, the question of the museum's purpose figures prominently. Four well-known artists have been invited to make up a story involving this world-famous museum, and the Louvre and NBM co-publish them. The first three have already been released:

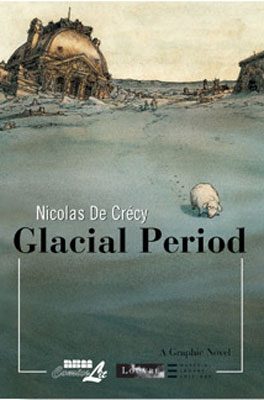

Glacial Period by Nicolas De Crécy,

The Museum Vaults: Excerpts from the Journal of an Expert by Marc-Antoine Mathieu, and

On the Odd Hours by Eric Liberge.

De Crécy imagines a time far in the future, when human history is lost and archaeologists are explorers attempting to find surviving artifacts and interpret their meaning. In a glacial period, or ice age, the cold, cold scientists find the buried Louvre and enter. They simply can't understand what they see, and their speculations on the purpose of the building and its contents are hilarious. Their adventure takes a fantastic turn that leaves the reader surprised, hopeful, and perhaps a bit dazed.

The art is beautiful. De Crécy was nominated for the 2007 Eisner Award for best painter. To tell a story which takes place in the Louvre is to paint many of the Louvre's treasures, and each painting De Crécy paints flows with a dedicated accuracy. De Crécy has a particular talent for animating the distorted and animal-headed icons of ancient civilizations. His painting relies on subtle use of colors, and he maintains a sharp artistic difference between the objects in the Louvre and the faces of his explorers.

I would have loved for this book to be larger-sized, but each frame of this 6x9 book is rendered with such perfect accuracy that even the ones that are the most densely packed with information are easily accessible.

Glacial Period is an absolute wonder, one of the most sophisticated artistic and literary graphic novels available in English.

Marc-Antoine Mathieu's

The Museum Vaults: Excerpts from the Journal of an Expert is a radically different kind of novel from

Glacial Period. NBM calls Mathieu "an artist who marries Escher with Kafka," and knowing this might help you find a helpful entrance into this darkly satirical and very funny story. On the first page, Day One, we meet Monsieur Volumer. He has just arrived at the "Musee du Revolu" (one of many anagrams of the Louvre used in the story), and his mission is to index and evaluate the museum's collection. By the story's finale, Day Eighteen Thousand One Hundred and Thirty Four, we've seen many absurdities at Monsieur Volumer's side. We've laughed our heads off, but what have we learned? That Marc-Antoine Mathieu is a master of, as the English say, taking the piss.

The Museum Vaults has different dimensions than

Glacial Period. It's 9x9, and one page has a wonderful fold-out. It's also done in two colors, and the drawings are bold and swaggering. Monsieur Volumer doesn't visit many of the museum's galleries, but when he does, the paintings are rendered as confident drawings that appear ready to be re-purposed as paint-by-numbers exercises. In one gallery, the cover of De Crécy's

Glacial Period hangs on the wall, several times and in several sizes, and rendered with tender accuracy.

I can't tell you how many times I've read

The Museum Vaults, because it's interesting, and there's always another visual pun I didn't catch the first time around. Mathieu's eagerness to joke is like a puppy's, and the funny bits land on every page.

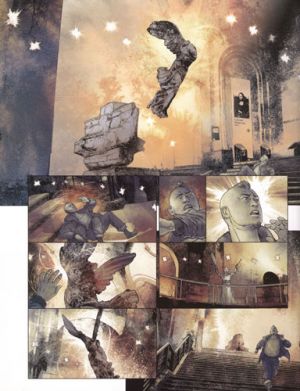

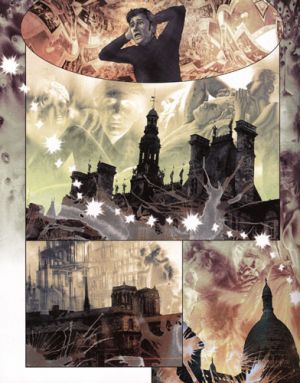

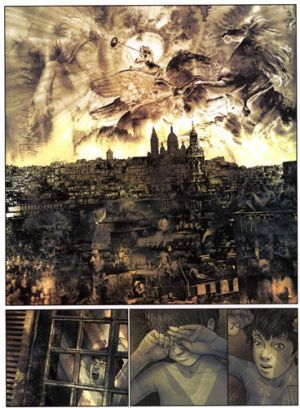

The latest in the series is Eric Liberge's

On the Odd Hours, a disturbing story about a young man hired to guard the Louvre "on the odd hours," the hours that no one else knows about. During those hours, the souls of the works of art are allowed to emerge and to taste freedom and self-expression before returning again to the material form that contains them.

What do you think the soul of an artwork would be like? I had actually pondered this question before, and I had thought they might be dangerous and uncontrollable, but I really hadn't thought it through. I think I'd imagined they'd be dangerous and uncontrollable, but that they would resemble the idea or thing they represent.

For example, the Winged Victory might be noble and demanding, or the statue of the 14 year-old Henry the Fourth might be a bit imperious, and insist upon hunting or practicing his archery. The point is, I thought they'd be predictable, even if perhaps unmanageable.

But in Liberge's hands, these souls of the artworks are entirely unique, and entirely unpredictable. They are, indeed, mirror images of the young man hired to guard them. Bastien is deaf, and has just about had it with the hearing world and its pressures on him to conform. What if – just what if – he could live on his own terms, not confined and suffocated by a world that defines him as disabled?

Bastien is not a hero, and the art is not sublime. There's a different logic operating here, and it will take patient reading, with judgment completely suspended, to locate and appreciate it.

The art is as explosive as the story and its main character, but I have bent your ear long enough. Instead, please enjoy these excerpts, and no matter what else you read this year, if you haven't read all three present volumes in the museum collection, you must.

Last Updated: March 3, 2025 - 20:40