Comics /

Comic Reviews /

More Comics

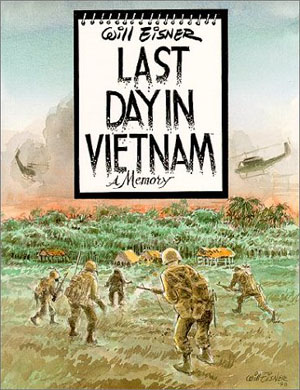

Last Day in Vietnam: A Memory Review

By Zak Edwards

May 8, 2013 - 22:32

|

The Vietnam War is a strange cultural experience, especially for people like myself, who weren’t alive for it. It seems to encapsulate so much of the cultural changes that happened in the United States during the Cold War, many of which have intensified or reversed (and then re-intensified) as we head further and further away from 9/11 while still having it right behind us. 9/11 and the Vietnam War are moments that wounded the world, real, cultural wounds, and are difficult things to process and integrate into an experience of our contemporary condition. These cultural wounds represent the traumatic experience of not just a single group of people, like the soldiers who fought in the Vietnam War, but a much larger population. Will Eisner was a man, as Matt Fraction says in his excellent introduction, ‘in the service’ during the fairly uncomplicated good-evil dynamic of World War II (even though anyone who’s read Kurt Vonnegut will completely disagree with this, for good reason). While Eisner was a soldier in that war, he made some pretty racy comics for servicemen in that period to teach them how to perform their duties. But this book, Last Day in Vietnam, is in part Eisner’s study of war after WWII, when the good-evil binary and the idea of the honourable soldier began to fall apart for the American idealist. Part of the reason the Vietnam War traumatized so many more than those in the actual battles was because this dichotomy of good Americans and evil Nazis was complicated: soldiers realized there was little actual honour when the effort was corrupt the whole way up to those forcing Americans into battle. After World War II, soldiers were able to get jobs, a free education, and parades were held to thank them for their ‘service.’. After Vietnam, soldiers were asked in interviews to show their arms to prove they weren’t heroin addicts. This says a lot about how the Vietnam War was taken and its impact on the American and Western psyche.

So, for the first, titular story, Eisner actually puts us into the eyes of a reporter, one who very closely resembles Eisner’s own history with the Vietnam War. The man assigned to this reporter is obviously lucky, a soldier who hasn’t had to really engage with the war effort. He is in the middle yet stands separate, in part because he comes from a family of soldiers that has afforded him certain privileges, but also because this advantage has insulated him from the experience. The story's perspective absorbs the reader entirely, juxtaposing the character’s lack of immersion into the war with the reader’s complete immersion. The first-person effect actually takes away your agency, in a certain capacity, you are addressed and you have your thoughts repeated back to you. You don’t really have any control and it’s pretty obvious that your escort through the war has no clue anyways. Three men are picked up in your helicopter at one point and, despite your guide trying to get them to smile, they don’t even talk. Only their dog makes a noise, and it is aggressive. The war has left these men in a silent anger, their dog’s emotions articulating what they no longer can. No wonder they came back with track marks, no wonder the rate of officers ‘accidentally’ killed in combat was so high. It’s strange that such an immersive story can lay bare so much of the anxieties of that period, but this is Will Eisner we are reading. The man himself. So experimentation and incredible storytelling is just a give in.

The other stories in this collection are significantly shorter, individual character pieces that formally experiment with how to tell stories. In one, “The Casualty,” a soldier permanently marred by war, wrapped in bandages that barely hide his destroyed hand, for example, remembers how he got his wounds. Encapsulating much of the sexuality of soldiers in wartime that is a major aspect of how the War is depicted, the protagonist thinks back to sleeping with a Vietnamese woman who then threw a grenade under his bed. The story is entirely silent and every moment is a wordless thought bubble of his experience juxtaposed with his retreat into alcohol and cigarettes. The story’s end, with him flirting with a different girl, speaks less to his own poor choices and more to his inability to properly articulate his experience. He can only remember without words, how is he to express this to anyone else? So, with the alcohol, cigarettes, and sex, he finds what he cannot speak.

Another story, of a man doing “hard duty” as a “wrench monkey” ends with him as the only soldier who regularly visits an orphanage for local girls impregnated by American soldiers. The underlying politics of sexual experience overseas is juxtaposed with the hard masculinity and the violence of the soldier. But here, a moment of complicated solace. The War brought tragedy, orphaned children, but individuals can make a difference. Eisner’s willingness to find these moments in amongst the murky politics of a war that ravaged the American psyche shows a balanced approach that, in the hands of less capable storytellers, would become preachy, soapbox-ish, and one of a million meditations on the subject. Here, Eisner’s approach offers moments that speak for themselves, speak to the tragedy and the politics in ways that take much of the political commentary for granted. Both a condemnation and a meditation on the shifting perceptions of war itself, Will Eisner’s Last Day in Vietnam tells seemingly simple stories that cannot ever be as basic as they pretend to be. They instead underline and bring to the surface many of the problems, the stereotypes, and regret of the period, only to leave the reader with a more humanist approach. Overall, the book's intense focus on individual characters serves as a broader analysis of the effects of the Vietnam War even in contemporary society, moving the war experience outside of rigid time and into our daily experience.

Last Updated: January 17, 2025 - 08:20