- Comics

- Comics Reviews

- Manga

- Comics Reviews

- European Comics

- News

- Comics News

- Press Releases

- Columns

- Spotlight

- Digital Comics

- Webcomics

- Cult Favorite

- Back Issues

- Webcomics

- Movies

- Toys

- Store

- More

- About

By Philip Schweier

September 30, 2014 - 14:09

With the release of the John Carter movie in

2012, I decided to revisit the Edgar Rice Burroughs books I read in my early

teens. Today, I offer an overview of his most popular creation, Tarzan of the

Apes. The dates following each title represent the publication of the

manuscript in book form, usually within a year or so following its magazine

publication.

Edgar Rice Burroughs

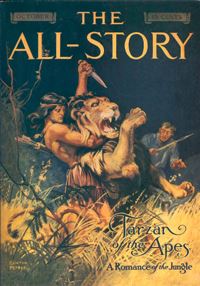

Today, the notion of an unexplored Africa is hard to grasp, but 100 years ago

when the first Tarzan story was published, it provided the setting for one of

the most popular characters of the 20th century. Following the debut of the

character in All Story magazine in 1912, the ape man became a

merchandising machine, featured in film, radio, comic strips, cartoons, toys

and television.

The Tarzan film franchise began in 1918 and ran until 1966 before migrating to

television the same year. Since then, there have been attempts to revive the

character in a variety of forms, though never with such success to challenge

other media juggernauts such as the Star Wars or Batman franchises.

In 1984, the film Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes, was

released. Written by Robert Towne (credited as P.H. Vazak) and directed by Hugh

Hudson – both multiple Oscar® nominees – the film was a grand Victorian

romance, more reminiscent of Bronté than Burroughs. One friend of mine

commented, “But that’s how the books originally were.”

No, not hardly. The first six books in the series are entertaining adventures,

providing the kind of pulp thrills one would expect. After that they begin to

deteriorate into an endless rehash of recycled concepts and predictable

narratives.

In the original Tarzan of the Apes (1914), we learn how Lord

and Lady Greystoke are marooned on the coast of Africa. Both perish after the

birth of their son, and the infant John Clayton grows up among the great apes

of Africa. He later meets Jane Porter and falls in love, eventually following

her to America, only to discover she is engaged to his cousin, the current Lord

Greystoke.

The first appearance of Tarzan in All-Story magazine

The book was a huge hit, leading to a sequel, The Return of Tarzan

(1915). The focus is more on adventure in general, less on Tarzan running

around the jungle like a wild man. His adventures take him from Paris to North

Africa and eventually back to the jungle. There, he discovers the lost city of

Opar and is reunited with Jane. Revealed as the true heir to the Greystoke

name, he and Jane marry.

In The Beasts of Tarzan (1916), their infant son Jack is kidnapped,

sending Tarzan on a quest to locate the boy and punish those responsible. Jack

returns in The Son of Tarzan, this time older, as he runs away to

Africa, living the life his father led among the creatures of the jungle. He

takes the ape name Korak.

By the fifth book, Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar (1918), the pieces were

in place. Tarzan was an English lord living in Africa, exploring the Dark

Continent clad in a loin cloth and armed with his father’s hunting knife, a

spear, bow and arrow, and a grass rope. He returns to the lost city of Opar to

replenish his family’s wealth, only to fall victim to amnesia as a look-alike,

Esteban Miranda, impersonates him elsewhere.

Jungle Tales of Tarzan (1919) is a series of short stories of a younger

Tarzan, chronicling various episodes set between the death of his ape mother

Kala and his first encounter with Europeans.

Tarzan the Untamed (1920) and Tarzan the Terrible (1921)

represent a combined epic, as the Great War comes to Africa, and Tarzan finds

himself swept up in the conflict. Believing Jane has been killed by the

Germans, he abandons his isolationist philosophy and exacts retribution.

Eventually, he learns Jane is not dead and follows her captors’ trail into the

interior. Burroughs introduced the land of Pal-ul-don, a hidden world of

prehistoric creatures and a race of tailed beings. This is the first of many

instances where Tarzan encounters two warring factions of a hidden race deep in

the jungle. Eventually, he is able to rescue Jane with Korak’s help, and

together they return home.

The ninth book in the series, Tarzan and the Golden Lion

(1923), builds further on the legend, adding Jad-bal-ja, a lion cub which

Tarzan adopts and raises. Tarzan returns to Opar, and once again encounters his

look-alike, Esteban Miranda.

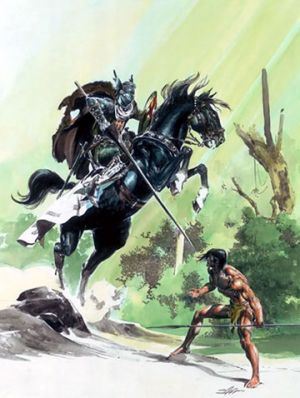

An unused cover by Neal Adams for Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle

Successive books in the series feature several variations on the “lost city”

plot device. Sometimes it is an undiscovered race, as in Tarzan and the Ant

Men (1924). Just as often it is a long forgotten outpost of a past

civilization, such as Medieval England (Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle,

1928) or ancient Rome (Tarzan and the Lost Empire, 1929).

The 13th book in the series may be a first in media history, in which one

existing series series crosses over with another (and, indirectly, a third). Tarzan

at the Earth’s Core (1930) tells of his adventure in Pellucidar, mixing the

two franchises. As the Pellucidar books and ERB’s Mars series both mention the

Gridley Wave – a radio transmission enabling communication between worlds –

which ties the Tarzan, Pellucidar and John Carter series as all occupying the

same “universe” long before it became common practice in the world of comic

books.

Tarzan returns to Opar for the final time in Tarzan the Invincible

(1931). Soviet agents invade the jungle intending to loot the lost city to

finance additional communist revolutions. Followed by Tarzan Triumpant

(1932), the story continues as Russian agents seek revenge for the failed

mission of their comrades.

In Tarzan and the City of Gold (1933), the ape man once more encounters

a lost city at war with its neighbor. Burroughs also recycles the look-alike

plot device for Tarzan and the Lion Man (1934), in which a movie crew

comes to Africa to film a Tarzan-like story of a man raised by lions. They

encounter a mad scientist and his hidden city of talking gorillas. The story

ends with Tarzan visiting Hollywood, where he undergoes a screen test for the

next Tarzan picture, only for the producers to decide he’s unsuitable for the role.

Tarzan suffers amnesia once again in Tarzan and the Leopard Men

(1935), pitting him against a jungle cult. Tarzan’s Quest (1936)

features the last major appearance of Jane, as the two become involved in a

search for a formula for eternal youth.

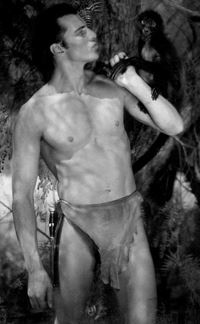

One of the most accurate film portrayals of Tarzan was by Herman Brix in 1935

By this time, the creative well had run dry for Burroughs. Tarzan had become a

multi-million dollar property, optioned for film, radio, comic strips and a

host of other products, including gasoline. Burroughs had established the

community of Tarzana, California, a Los Angeles suburb. Many of the books that

followed descended into variations on the writer’s two favorite plot devices:

lost civilizations and look-alikes.

In Tarzan and the Forbidden City (1938), Tarzan is recruited for an

expedition in search of Brian Gregory, a young explorer who looks like the ape

man. Gregory is discovered in a hidden city at war with its neighbor. In Tarzan

the Magnificent (1939), he returns to the lost cities of Athne and Cathne,

previously seen in Tarzan and the City of

Gold.

Tarzan and the Foreign Legion (1947) was the last Tarzan novel published

in ERB’s lifetime. In it, Lord Clayton is serving in the RAF, fighting against

the Japanese in the Pacific. Forced to bail out over Sumatra, he is joined by a

motley band of freedom fighters in the jungles of Southeast Asia.

The final two Tarzan books were published in mid-1960s, both consisting of

unpublished manuscripts. Tarzan and the Madman (1964) was another

variation on the lost civilizations and look-alike storyline. Tarzan and the

Castaways (1965) is actually three stories: the title novella, in which

Tarzan discovers a lost outpost of Mayans on an uncharted island; Tarzan and

the Champion pits him against a brutal boxing champion hunting wildlife in

Africa; and Tarzan and the Jungle Murders, in which Tarzan turns

detective and solves a mysterious pair of murders.

However, a year after the publication of the last Tarzan story

written by Burroughs, a 25th novel entered the Tarzan canon. Tarzan and the

Valley of Gold (1966) by Fritz Leiber was adapted from an original

screenplay by Clair Huffaker. Based on one of the last Tarzan films produced

for the “official” film series, the story takes Tarzan to the jungles of

Central America in search of a lost horde of Mayan gold.

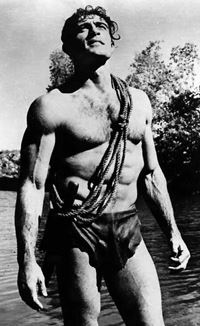

Mike Henry played Tarzan in the mid-1960s

Lieber's writing style is radically different than Burroughs. Rather than

portray events in the story, many segments feature extended dialogue between

characters as they explain what has happened. This makes for a rather dull

narrative compared to earlier stories.

It would be almost three decades until the next Tarzan novel. In 1996, author

Joe R. Lansdale completed an unfinished ERB manuscript, later published in

comic book form as Tarzan: The Lost Adventure. In the story, Tarzan

watches over an expedition searching for the lost city of Ur, whose inhabitants

worship a monstrous creature that Tarzan believes originated in Pellucidar.

Two additional novels were later added to the official Tarzan canon. In 1996,

R.A. Salvatore adapted the pilot episode of Tarzan: The Epic Adventures

into novel form. In 1999, Philip José Farmer, who had written the Tarzan

“biography” Tarzan Alive (1972) penned The Dark Heart of Time. It

takes place between the books Tarzan the

Untamed and Tarzan the Terrible.

The first Tarzan story was sub-titled “a romance of the jungle,” and this is a

common theme that runs through virtually all the books. Tarzan’s devotion to

Jane is featured extensively whenever possible, but often supporting characters

are the subject of developing sub-plots. Often, it is a case of a typically

clueless male being unaware of the attraction, leading to romantic conflict.

Another theme common to the stories is the inherent innocence of the animal

kingdom. Tarzan often comments on the greed and corruption of man, compared to

that of animals, who will kill only in defense or for food.

Many supporting characters are painted with a rather broad brush, bordering on

comic stereotypes. It seems rare that the stories feature agreeable supporting

characters without an equal dose of scoundrels, but such stories would hardly

lend themselves to an entertaining adventure.

Part 1: John

Carter of Mars

Part 2:

Pellucidar