Comics /

Spotlight /

Knowledge and Scholarship

A New Theory of Comic Book: Part 2 – Art and Business

By Hervé St-Louis

October 29, 2009 - 21:39

In my first article detailing my quest for a new theory of the comic book, I wrote about philosophical questions. I asked how I and you know what we know about comic books. My answer to that was that as every comic book historian has his biases, we should be careful of them. I’ve decided to wear my biases on my sleeve, and use them in the building of a new theory of comic books. This is a quest I really started last year, when it felt to me that the research methods offered by constructivism might have some interesting answers. Before you tune out because I’ve used the word constructivism, let me explain further what it means.

|

Constructivism is part of a whole post modernist approach to the study of everything we know. There are constructivist methods in communications, literary criticism, history, sociology anthropology – you name it. Constructivism assumes that the researcher studying a topic or a field construct his own paradigms and definitions and that in turn these will influence what we find out about the object of study. For example, to study war, hunger or comics, the researcher defines these terms. Constructivism is much more complex than described above, but suffices it to say, there has been a very good book written by French scholar Thierry Groensteen (The Systems of Comics) which used an approach akin to constructivism to study comic books. He literally identified the lowest unit in a comic book and tried to explain how comic books work by looking at them from that minimalist perspective.

This minimalist perspective is not something I was indifferent to. For example I wrote last year about my own absolutist views of comic books based on the theory developed by Scott McCloud, but going further. I’ve identified

many schools of thoughts that interpret comic books differently. There is the “word and picture” that argues that comic books are a combination of imagery and text. There is the formalist school advocated by Scott McCloud that says that comic books are based on closure. Closure is the space between two illustrations requires the user to fill in the gaps of the action with his mind. Then there is what I called the Juvenile school that argues that comic books are for children. How the comic books are built is irrelevant for this school of thought. All that matters is for whom comic books are intended to.

Because there are many ways of

explaining comic books, there are also many biases in the work of those that explain them to us. I’m fully aware of my own biases and think they offer an opportunity to look at comic books in a different way. If you had a spectrum, you could put the juvenile school on one extreme and the constructivist work of Groensteen on another. One looks at comic books as a social artefact made for a specific target group. The other looks at comic books as a line on a piece of white paper. Where I’m going with comic books follows in a way the work done by others, but in a novel configuration. An important article that influenced me – or dare I say pushed me even more in the direction I’m taking is an article by

Comic Book Bin editor

Patrick Bérubé on floppy comic books as artefacts. He bemoaned the fact that trade paperbacks are becoming the preferred format of printed comic books and that many people wish that the floppies – the 22-40 pages comic book sold as periodicals are rejected by many pundits as detrimental to the comic book industry. I had been a partisan of trade paperbacks myself, whether they were compiled editions or graphic novels. The floppy comics survives, still, but many wish its death. Again, I have to argue that one of the reason pundits don’t like floppies is because they are seen as juvenile and disposable material. I theorize and am certain that this is one of the main reasons they are not liked. They remind pundits of the lowly origins of comic books and how people outside of comic books perceive them negatively.

I believe that the comic book as an artefact is not something that should be thrown away or not given proper consideration academically. I also believe, that how comic books are studied and discussed, must not remove the art and narrative part from the actual delivery format they come in. I base this on a simple proposition. The majority of comic books are not unique artefacts found in museums or private collections. They are copies of an original artefact. The original artefact - the actual comic book page or the design created digitally is usually not on display for the multitude of comic book readers. When you log in on a Web comics site to read the latest instalment from your favourite creator, you are always reading a copy of his original work. When you buy a comic book at the store, again you are buying a copy of an original. Even the self publisher that makes only five copies of his mini-comics and distributes them to his local comic book or record store, is distributing multiple copies of an original work. This process has led me to theorize that if the majority of comic books are always copies of an original, therefore the process of making the copies involve business decisions. If business decisions are involved in making sure a comic book reaches a reader, therefore, the business acts involved in delivering that comic book becomes important in the study of the comic book as the actual artwork and narratives contained in the comic book. The comic book is thus an artefact whose nature is to be a multiple of an original.

|

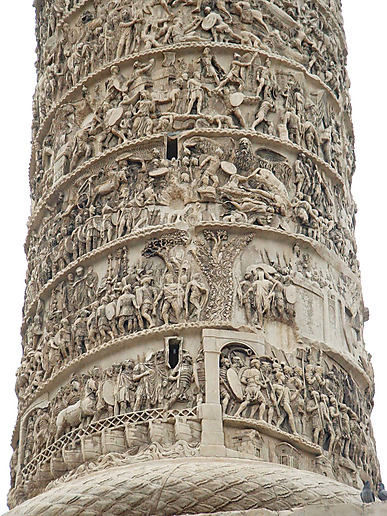

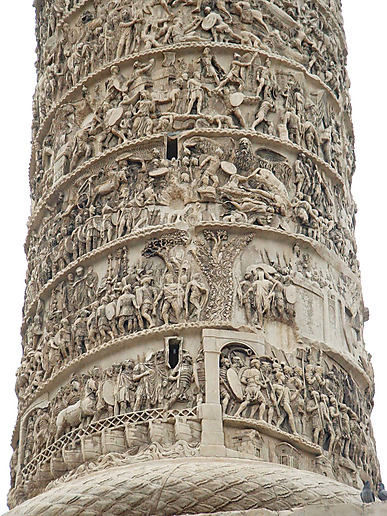

Without the business side, there are no comic books. There is of course the exception of the single comic book that was never duplicated created by a creator for say a private collector, a museum or a public square. These, like Trajan’s column in Rome (which is sequential art or the name of the art form comic books and storyboards are based on) are truly unique and can escape our requirements to be studied as piece of art as well as artefacts with a business history. But everything else, whether it is a mini-comics, the latest issue of

Love and Rockets,

or

Superman/Batman comics are all artefacts that should be studied as both art forms and products. So far the majority of research on comic books has centred on their artistic values. I’m curious about their artistic value as well as their value as consumables. This raises many questions like why did the creator choose recyclable paper to print his comic books? Why do they have foil covers and multiple covers? Does it matter if only 5,000 copies were distributed? What can the $2.99 price tag tell us about the cultural group that is willing to buy a comic book at that price? There are so many questions that can be asked that it just opened up a whole new way of understanding comic books.

But as I wrote before, this is one of my three main biases towards comic books. My first bias is that

I love comic books. I covered that in the previous article about how that affects the study of comic books. My second bias is that the artistry is equal to the business side when studying comic books. Finally, my third bias is that Studying readers’ interaction to comic books is equally important as studying the art of making comic books. We’ll look into that aspect of my new theory of comic books in the next article in this series.

Last Updated: January 17, 2025 - 08:20