Comics /

Comic Reviews /

More Comics

Che: A Graphic Biography

By Arch Snite

November 7, 2015 - 15:58

Before I begin this review of Che: A Graphic Biography, by Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colon, a little irony as an appetizer: Sid Jacobson, who co-wrote this book about a marxist leader, created Richie Rich. You can’t write this stuff. But he did anyways.

It’s fitting that Che Guevara has become equal parts t-shirt fodder and rifle fodder, because it reflects what a disposable punchline of a human being he was. Che-haters (from hereon, Che-ters) are often angry to see a bloodthirsty murderer adorning trendy clothing items. Che-ters look at the shirt’s popularity all wrong, however. If the novelty wardrobe item fits, wear it! The shirt’s so ubiquitous it resembles a meme, which is apt because so many things about Che resemble memes and viral videos.

But, before you start reading…

— youtube “Ren and Stimpy Soundtrack - Happy-Go-Lively” because that’s perfect accompaniment to list-reading.

— hit play

— begin reading following article.

HONEY BADGER

Che was sort of the honey badger video before its time. Che’s been referred to by Jean-Paul Sartre as “the most complete human being of our time— our era’s most perfect man.” Che really doesn’t give a shit. If he was bloodthirsty, he was bloodthirsty. He don’t need no due process in his trials. He just executed who he wanted. Oooh, look at that badass sign another death warrant! Che was pretty bad. He had no regard for other people if they got in his way. Case in point, he decapitated an adolescent boy (see below) for mouthing off and defending his father.

CARL FROM LLAMAS WITH HATS

CHHHHEEEEE THERE IS A DECAPITATED DISSIDENT IN THE COURTYARD

Poor Che. He kept murdering people and screwing up, compounding absurd incident on absurd incident, just like Carl in Llamas with Hats. Was the resistance leader a coward and a scoundrel? Push him into a giant fan. Was the lovely elderly couple in 2B hogging all the crescent rolls? Turn them into boat nectar. Were other guerrillas hesitant to execute Eutimio Guerra? Che strolls right up and shoots him in the head. Was there a possibility of nuclear war between America and Russia? Support the notion that New York should be reduced to phosphorescent ash. Che would not apologize for art.

Fittingly, Che’s relationship with Castro eventually became like Carl’s with Paul’s— just like Paul got a restraining order, Castro distanced himself from Che: “Know what I’m going to do with Che Guevara? I’m going to send him to Santo Domingo and see if [Dominican dictator] Trujillo kills him.”

|

| Add beret for instant leftist saint. |

BAD LUCK BRIAN MEME

Where was Che Guevara, the self-described military man, during the Bay of Pigs invasion? He was getting fooled off his ass by CIA rowboats filled with fireworks, mirrors, and a tape of battle noises. It was at this “battle,” however, that he was almost killed…by his own gun. Which fired through his jaw and exited out the front of his temple. A bullet enters Che Guevara’s head from his own pistol and doesn’t kill him. That’s the definition of history and misfortune ganging up to hump humanity’s leg.

GRUMPY CAT

Che, like a lot of Marxists, didn’t really believe in joy or happiness. Che’s entire life is sort of a Tardar Sauce reaction to people who disagreed with him. Were rock musicians and gay Cubans posing a threat to the revolution (don’t ask, it’s marxist logic)? Arrest, torture and maybe murder them.

SPOILERS: in the same way there’s no crying in baseball, there’s no spoilers in history. There’s only the need to read more. So you’ve been sort of warned.

Che: A Graphic Biography, by Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colon, is giddily sterilized hagiography that would go well as a companion piece to your average Occupy protestor’s Che Guevara shirt: cheaply crafted, overpriced, and soiled by the figurative pit-stains of factual inaccuracies.

Some facts in

Che: A Graphic Biography are true enough. Che’s early trip through South America shaped his political views, his role in Castro’s Cuban revolution made him famous, and he was eventually killed in Bolivia by a CIA-assisted team of Bolivian soldiers. One positive feature of

Che is Jacobson and Colon’s decision to tell the story as a linear narrative. Since their stated purpose is to write a biography, beginning-to-end is always a good way to go. If only they were right about things.

|

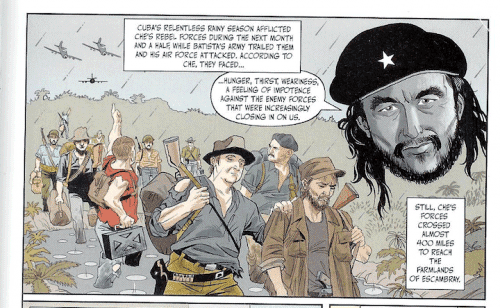

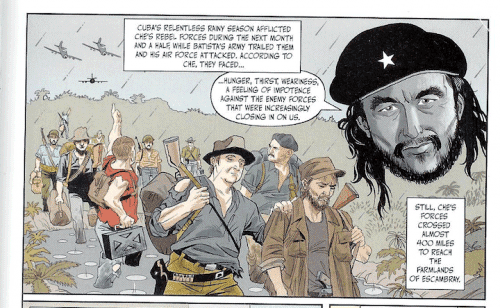

| Che's enormous unsettling disembodied face was always an inspiration to horrified Castroites. |

Though

Che’s linear structure is fine, its elaboration is “a catalog of swindles and perversions,” to quote George Orwell. Propaganda is presented as reality, research is ignored, and Jacobson and Colon’s outdated dependence on authors like Che biographer Jon Lee Anderson— who depended heavily on biased Cuban government sources— fail to account for eyewitness reports or dissenting opinions. They pay lip service to fairness on a few occasions. A one-page afterword quotes three negative opinions about Che. This hardly counters the book’s presentation of the facts, however.

Omitted facts and fanciful visuals compromise the historical value of

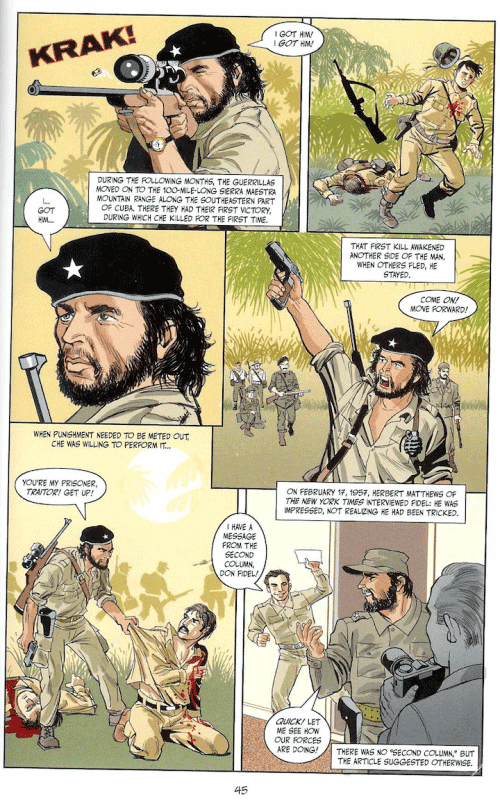

Che: A Graphic Biography. Jacobson and Colon have a veteran press secretary’s ability to gloss over atrocities. The visuals don’t so much contribute to the narrative as gild the factual void at the book’s center. It takes another marxist, actually, to fathom the inanity of the visuals. What the French critic Roland Barthes said about photographs of politicians applies here. Barthes argued that pictures of politicians “establishe(d) a personal link between him and the voters; the candidate…suggest(s) a physical climate, a set of daily choices… a way of dressing, a posture.” In other words, politicians know that single pictures are worth a thousand platforms. The famous t-shirt image of Che might be the best example of this in the second half of the twentieth century. Barthes argued that even the tilt of a person’s head can suggest something: “A three-quarter face photograph…suggests the tyranny of an ideal: the gaze is lost nobly in the future, it does not confront, it soars, and fertilizes some other domain, which is chastely left undefined.” Fitting, then, that Jacobson and Colon couch Che’s first killing in a three-quarter face image.

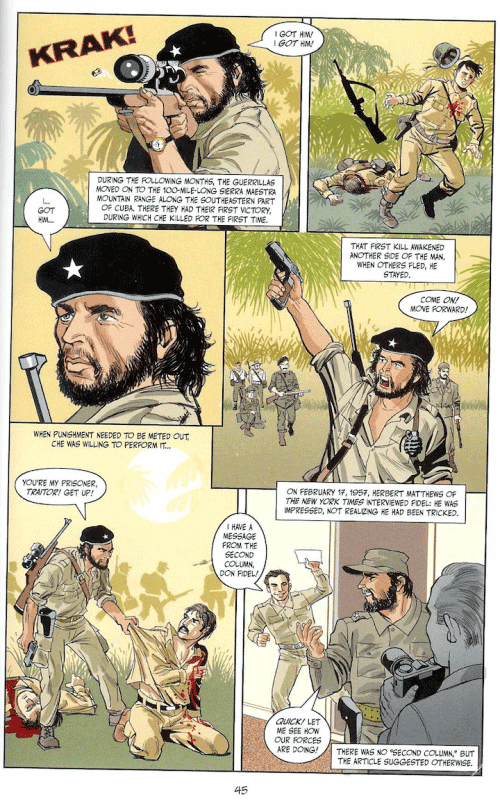

|

Here’s Jacobson and Colon’s take on an early killing by Che. There’s no realism. Che comes across more as an orthodox icon than even an image of a person. Che executed plenty of people, but all Jacobson provides is posturing figures that resemble children playing army: Che sighting an enemy, Che raising a pistol in romantic fashion, and Che, armed to the teeth, saying “you’re my prisoner, traitor! Get up!” to a comfortingly generic enemy. There’s not even a smidgen here of the sort of kinetic honesty that makes a war comic like Kubert’s Sergeant Rock a classic.

The page’s focus is a single panel in the middle, an image of Che in that same three-quarter profile Barthes mentioned, suggestive of the famous t-shirt image. Having shot an enemy, Che stops and stares meaningfully into the middle distance: “I…got…him.” The humanistic hesitation suggested by this image is in stark contrast to a real story about Che killing in the field. When Castro ordered the execution of a Batista spy within his army, his soldiers were hesitant. Even Castro’s bodyguard, Universo Sanchez, seemed reluctant: “Sanchez was hesitant, looking around, perhaps looking for an excuse to postpone or call off the execution. Dozens would follow, but this was the first execution of a Castro rebel. Without warning, Che stepped forward and fired his pistol into Guerra’s temple.” In a letter to his father, Che admitted: “I’d like to confess, Papa, at that moment I discovered that I really like killing.” There’s no mention of this in

Che: A Graphic Biography. There is mention of another of Che’s crimes against humanity, but, little surprise, it’s also whitewashed.

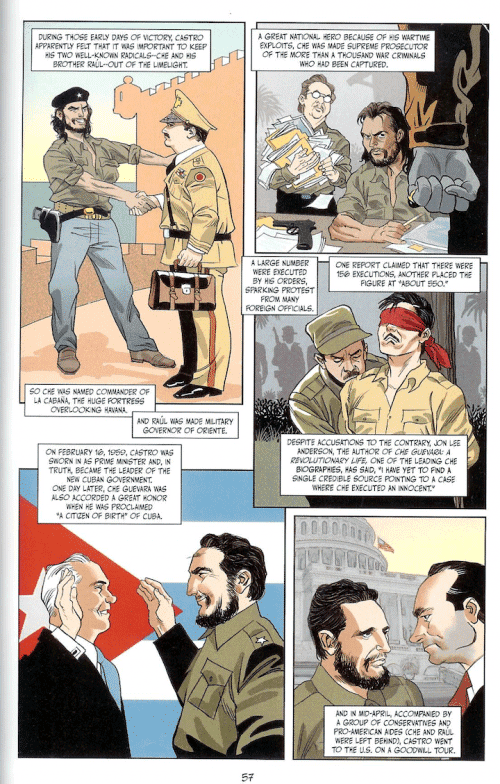

Jacobson and Colon say that “Che was name commander of La Cabana, the huge fortress overlooking Havana.” Calling “La Cabana” a “fortress” is sort of like calling Buchenwald a military base. True? Well, sure, in that both housed army personnel and commanding officers. But here’s the tricky thing: both were death factories. Estimates of executions in the first three months alone of Che’s command, based on eyewitness accounts, range from 400 to 1,892. To Jacobson and Colon’s credit, they do refer to these executions. Maybe “credit’s” the wrong word, though, as they gloss over the bloodshed in two panels, and give the final word to biased Che biographer Jon Lee Anderson, who claims “I have yet to find a single credible source pointing to a case where Che executed an innocent.” This quote comes under an image of a soldier dutifully tying the hands of a stoic firing squad victim.

What did the executions actually look like? Here’s one of Anderson’s— and Jacobson and Colon’s— not-so-credible, eyewitness sources:

“…Che’s guards shoved a new prisoner into our cell. He was a boy, maybe fourteen years old…soon Che’s guards returned…they yanked the boy out of the cell…then we spotted him [Che], strutting around the blood-drenched execution yard with his hands on his waist and barking orders… ‘Kneel down!’ Che barked at the boy…the boy stared Che resolutely in the face. ‘If you’re going to kill me,’ he yelled, ‘you’ll have to do it while I’m standing! Men die standing!’…then we saw Che unholstering his pistol. He put the barrel to the back of the boy’s neck and blasted. The shot almost decapitated the young boy.”

The story comes from someone who watched the execution from his cell. This execution was one of at least several hundred. Even when Che wasn’t killing prisoners himself, he was busy signing death warrants in assembly line fashion like a hanging-judge Henry Ford. Little wonder Colon and Jacobson lack the courage to even suggest that the victims weren’t always able-bodied soldiers. The only phrase they use to refer to the victims? “War criminals.” The fourteen-year-old in the above story was jailed for fighting the soldiers who came to take his father to the firing squad. I suppose that if Colon and Jacobson can call La Cabana a fortress, defending a family member can be a war crime.

In the past year, America’s reestablished ties with Cuba, which still depicts Che the murderer as a hero. There’s an entire mausoleum to him in Havana where visitors aren’t allowed to look away from the image, laugh, cough, or otherwise disrespect Che’s picture. In the past month, it's become clear that Cuba's now sending its own special forces to aid Bashar Assad's murderous regime in Syria. Jacobson and Colon’s book is a useful primer for America’s renewed relationship with Cuba. The malleability of truth, the omission of messy details like state-sponsored murder, the worship parading as realism— this is, sadly, a book very much in line with our president’s fancifully forgiving view of the world.

Vive el Cuba libre. Vive el cristo rey.

Last Updated: January 17, 2025 - 08:20