- Comics

- Comics Reviews

- Manga

- Comics Reviews

- European Comics

- News

- Comics News

- Press Releases

- Columns

- Spotlight

- Digital Comics

- Webcomics

- Cult Favorite

- Back Issues

- Webcomics

- Movies

- Toys

- Store

- More

- About

By Andy Frisk

September 27, 2009 - 22:36

|

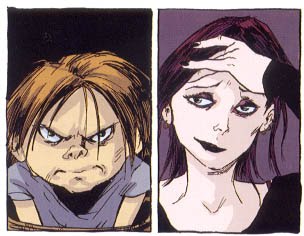

The world, or at least the world in Ball Peen Hammer’s setting city, is deteriorating. Plague, bombings, contaminated water, spotty electrical and plumbing services, acid rain, and a Syndicate and Fellowship, both with odd directives, rule. The Syndicate murders and drives out the community of artists eking out an existence in the “Undertunnel” while The Fellowship takes volunteers for their unexplained child killing and body harvesting operation. A Dragger helps drag the bodies back to the basement of the city’s irreparably damaged clock tower, and a Sacker performs the killing with a double tap to the back of the child’s head with a ball peen hammer. Into this nightmarish world are introduced the following characters: Welton, a guitarist/singer and current Dragger, Aaron Underjohn, a novelist and soon to be Sacker, Exely, an Uptown actress (Uptown being a “clear zone” apparently) who’s searching for Welton, whose child she is carrying, and Horlick, a neglected street kid who lives in the top of the clock tower. If you’re thinking this tale sounds like some kind of experimental, off-off Broadway, avant garde, four man play, then you’re not completely off the mark.

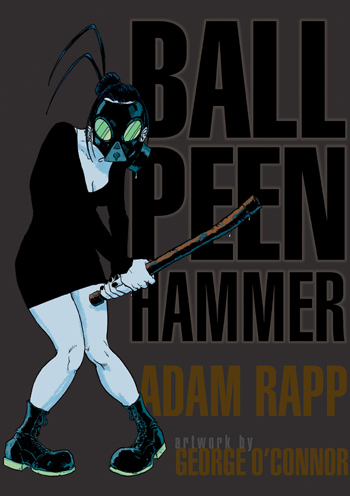

Ball Peen Hammer is the first graphic novel written by Adam Rapp, who can add, amongst the titles of novelist, playwright, screen writer, film maker, and Pulitzer Prize Finalist, the title of graphic novelist to his repertoire. His skills as a playwright transfer well to the graphic novel format, and Ball Peen Hammer reads, moves, and is laid out in a very play-like manner. We don’t get much back story on this nightmare world of plagues, bombings, and odd organizations, but we do get a lot of staccato dialogue along with tense, at times touching, and other times revolting human behavior and interactions. The work truly is “an unflinching meditation on art and human nature,” as the inside cover of the book states. It’s the type of work that is laden, almost too heavily, with unspoken and interpretable meaning. It’s also the type of work that can eternally tie up graduate students in literature, creative writing, or possibly even theatre, in unending interpretational debates and dialogues. This is not a bad thing. An interesting work of art should simultaneously inspire creative interpretation as an exercise for the mind, and tie up it’s readers in fruitful interpretative discussion. Ball Peen Hammer certainly accomplishes these goals.

|

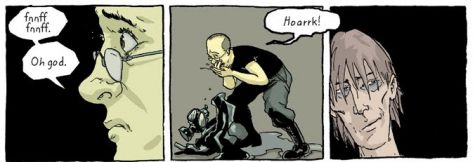

Being a graphic novel, readers who enjoy such literary debates get the added bonus of interpreting George O’Connor’s artwork as well. It is jagged and slightly out of proportion, reminiscent of Alberto Ponticelli’s work on DC Comics’ Vertigo series, Unknown Soldier. The world of Ball Peen Hammer has devolved into a nightmare, and O’Connor captures this nightmare well. His depiction of the plague victims in particular is disturbing, but no more disturbing than the entire work overall. He also follows Rapp’s script well, and really captures the playwright/film maker’s visual direction. The panels rely on perspective placement of the reader’s eyes to move the story along, and for several panels there isn’t even any dialogue, and the story is advanced solely through O’Connor’s images.

|

This definitely is not a work for the faint of heart or “gentle readers” as the quote from Booklist states on the back cover. For mature readers, grad students looking for extra credit, and curious, intelligent readers looking for something to exercise their interpretive literary theory powers, Ball Peen Hammer is just the ticket. At the risk of sounding pretentiously jargon laden (you know, the type of writer/article that The Comics Journal would meet with “howls of derisive laughter”), Ball Peen Hammer is approachable from an existentialist, post colonial, new historical, gender, queer, and the most derided of theoretical approaches these days, the post-modern interpretive stance. Don’t let all this literary talk turn you off from considering picking up the work though. You can enjoy Ball Peen Hammer’s artistic power without thinking too hard.

Perhaps “enjoy” is too strong a word when considering this work. Make no mistake, it’s incredibly dark, provides little answers, and there are no happy endings. You will absorb it, let it under your skin, and only discharge it after thinking it though and putting in up on the shelf, thus exorcising it from your mind. It’s a worthy trip though, as great art should get under your skin and make you think, at least a little.

Rating: 9 /10