Comics /

Comic Reviews /

DC Comics

Animal Man #1

By Zak Edwards

September 14, 2011 - 12:09

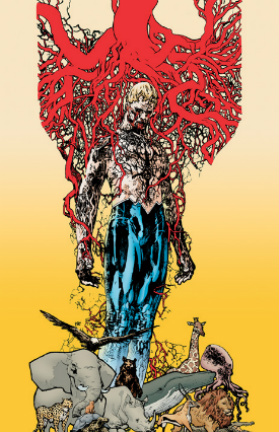

I am trying to be discerning in my engagement with this DC relaunch, as I am sure many are. Grant Morrison’s Action Comics seems like a no-brainer, and be sure to check out the reviews my fellow Bin writers have said about Morrison’s re-imagining; but Animal Man has a premise I find very interesting, and not simply because it is written by Jeff Lemire, DC’s best acquisition in years. While many of the other relaunches seem about taking the characters back from their mid-thirties sort of life stage to a mid-twenties point, Animal Man is a family man: a hero with responsibilities and relationships that matter. Also, barring the Fantastic Four, the superhero with a family doesn’t really seem to be a thing for many mainstream heroes, and Lemire seems to be doing something different from Marvel's First Family. As a side note (and as the cover may suggest): Animal Man isn’t really a kid’s book, in my opinion, as there is some fairly scary and graphic sequences inside.

|

Animal Man starts with a full page interview with Animal Man for a magazine and gives readers an opportunity to know protagonist Buddy Baker through the eyes of public perception and media before seeing him on his own. The tactic may be off-putting for some, but works well. Lemire even manages to drop a sly reference to Grant Morrison’s run by putting his own name on the interview and establishes specific viewpoints beforehand that factor into the story. Thus, when the character is seen for the first time, he is immediately familiar and already disturbing these perceptions given by controlled media outlets. But despite Animal Man's quasi-famous status, the series lacks a media craze; Buddy doesn’t have paparazzi issues and journalists aren’t camped out all over, trying to see him at his worst. Instead, people have a generally decent relationship with a hero whose identity is very public, up to and including the police. Lemire keeps things focused and small in the first half of the issue, with his family having fairly mundane interactions, including the best line in the entire issue, given by his little daughter: “Mr. Woofers and I have a great idea. We think you should by us a pet doggy to play with.” Lemire’s family interactions are believable and wonderfully normal, grounding Buddy’s life and making the next two thirds much more weighted. And while the shooter at the children’s hospital does seem contrived, especially with Buddy’s constant “this relates to my life so well” comments, it does reinforce Buddy’s differing situation from most heroes.

But the second half of the issue is where the series confidently establishes the tone and direction. If the first half can be considered mostly general setup, despite being very high quality and interesting, the second half sets the series' position with such authority, one cannot help but be intrigued. Taking the form of one of Lemire’s trademark dream sequences, something used in his best-selling series Sweet Tooth and harkening back to the old line of Vertigo comics, Buddy encounters his family and some larger than life forces that seem far too strange and ethereal to be considered conventional antagonists. But by the end, the focus is on the family, as it were, and sets up an impossible, intangible enemy with the much more real family issues, even if the latter is firmly entrenched in the superhero frame of reference. I look forward to the balance and unique perspective this book promises so early on.

At the outset, and certainly for the first half of the book, I was unimpressed by artist Travel Foreman. He appears to have a style reminiscent of Mike Allred (of Madman, X-Force, and Fables fame) but without much of the pop art sensibility Allred draws from. His characters can look very strange and often have a glaze on them that makes them look far too shiny or made of glass. Coupled with his minimal backgrounds and seemingly random changes in colour on faces during close-ups, Foreman’s style seems to almost highlight certain weak points, relying on the quality of his pencils and singular objects which sometimes need accompaniment. However, by the second half, Foreman is an obvious choice for this book. Coupled with the inking of Dan Green and colouring by Lovern Kindzierski, foreman’s art blossom’s in the black-and-white dream sequences. Foreman’s art is simply better with busier panels, more definitive lines, and more careful use of colour. The same is true for the stranger panels in the first half of the book, including the brief action sequence, where the heavy lines and inking create bold spreads that highlight ability over action. Really, Foreman is at his best at the strangest moments, where he is free to explore, just look at the cover. Hopefully Foreman can balance his approach in order to aid the more mundane aspects of the book, which are wonderfully interesting, and the crazier sequences that are obviously equally important.

Grade: A- Probably the best of the New 52 I have read so far and a high bar to set so early on.

Last Updated: January 17, 2025 - 08:20