Comics /

Spotlight /

Religion and Comics

Alan Moore's Light of Thy Countenance

By Beth Davies-Stofka

September 1, 2009 - 11:44

This graphic novel is an adaptation of a short story composed by Alan Moore in 1994 and published in an unremarkable anthology called

Forbidden Acts (Avon Books) in 1995. The adaptation, by Antony Johnston (

Wasteland), faithfully preserves every word of the original composition by Moore. This might be the worst feature of the book. Well, actually, the worst idea was doing it in the first place.

I haven't heard Moore's spoken word poetry in his own voice, but I can imagine that it would be fun and satisfying to hear

Light of Thy Countenance performed live in a theater accompanied by interpretive performance art, especially if said interpretation were satirical in intent. Moore's exceptional intelligence and his depth and breadth of knowledge are all on display in this experimental story. But while Moore is likely not a native of the planet Vogon, this torturous monologue crawls across 48 endless pages, making its reader long for the blessed oblivion of the airlock.

Light of thy Countenance is television's stream-of-consciousness meditation on its birth and its eventual global dominance. It tells us:

Sometimes in the dot and dazzle I forget myself.

Become submerged, become embedded in the bright, face-flickered current of the photogeists; the exo-souls adrift within the Bairdo.

Sometimes, in the vast omniscient hiss of me I am amnesiac, senescent luminescence of my world-sized thoughts dissolved in a variety of soaps

Or smashed to sparks by glassy hammer-fisted glowtides, information breakers foamed with car-chase,

chocolate and hallucination, shattered on the reefs of cone and rod , against retinal inlets,

crash of light amongst the tidal debris, long-dead image-claw, husked thorax of idea, the laugh track spray flung shrill and high

And I forget that I am as a god

And lose myself amongst my empty angels.

And yes, it goes on like that for 46 more pages. First television loses itself in Maureen Cooper, a 16-year stalwart of a television series called

Jubilee Terrace. But wait, Cooper isn't real. She's played by actress Carol Livesey. And wait, that's not Carol's real name. Carol Livesey is actually Carol Sugden, who is kind of a sweet person. As Maureen becomes aware of Carol Livesey/Sugden, her illusion is shattered, and she returns to full awareness of what she really is: television, a construct both metaphysical and ubiquitous, born from paranoid delusion and scientific experimentation, and grown into a monstrous hypnotic force that controls the world's billions by distracting them with pointless banality.

Superior people, of course, don't watch television. At least, that's the implicit claim. Through his adaptation, Johnston adds a great deal of vivid interpretive imagery to Moore's original story. At one point we see a red-blooded young couple break up. As they watch television together, the young man becomes too involved with the images on the screen to pay attention to the young woman. As she leaves, he reaches into his pants and satisfies himself while his eyes remain fixated on the screen. Like that actually happens!

The scorn Moore seems to feel for those who actually watch television is exaggerated by Johnston's adaptation. It is important to any society for its finest minds to critique its central modes of communicating, and you can read very good critiques of television. The best is Neil Postman's

Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business (1985), or if you want to go straight to the source, read Aldous Huxley's

Brave New World. It is another thing entirely to heap derision and contempt on your fellow human beings, under the presumption that you know what goes on in their minds when they put their televisions on.

While there are many virtues to the ancient traditions of magic, shared by every human culture this earth has seen, magical thinking is also flawed. Magic can be quite powerful, but it can also be a cruel trickster. One of the cruelest of its tricks is convincing people that they can and should attempt to obtain power over others. Moore seems to credit television with this kind of magical power, but in the real world, television is not a metaphysical entity with purpose. It is material, and dependent on any number of material and economic forces. It's dependent on investors, advertisers, creative geniuses, and bureaucrats. It's dependent on the ongoing availability of a relatively inexpensive power source, and above all, it's dependent on people choosing to watch it. From everything I hear the numbers of those choosing to watch it are steadily dropping.

Another review of

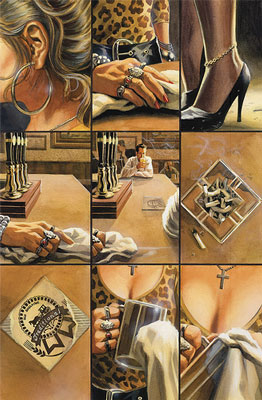

Light of Thy Countenance might choose to ignore how boring and insufferable it is, and focus on the art. Felipe Massafera's high-quality photo-realistic pages, similar in look and style to Alex Ross's award-winning work, is terrific and complements television's slow self-examination in a number of interesting ways. The book's imagery also serves to amplify the religious and historical overtones of Moore's original piece. But the art won't strike you as special unless you read the words, and that is not something I can recommend.

Rating: 3 /10

Last Updated: January 17, 2025 - 08:20